Cypress Point Club

Cypress Point is one of the most overwhelming golf courses in the world—the product of an all-time great architect getting his hands on an all-time great piece of land

Pebble Beach, California, USA

Alister MacKenzie (original design, 1928)

Private

$$$$

Cypress Point | Site of the 2025 Walker Cup Match

Everything You Need to Know for the 2025 Walker Cup at Cypress Point

Deep Dive: Cypress Point

Pebble Beach Golf Links is often called "the greatest meeting of land and water in the world." (This phrase was first used by the artist Francis McComas to describe Point Lobos, a nearby nature reserve.) Pebble Beach's neighbor on 17 Mile Drive, Cypress Point Club, might be the greatest meeting of a property and an architect in the history of golf.

When Alister MacKenzie and his lieutenant Robert Hunter broke ground at Cypress Point in late 1927, MacKenzie was at the height of his considerable powers. He was the R&A's go-to architectural consultant; he had established a beachhead for his practice in California; and he had recently visited Australia and New Zealand, where, in a three-month flurry of activity, he changed golf in that region forever. One can imagine MacKenzie's excitement to apply his talents to Cypress Point's unique mixture of pine and cypress trees, dunes, and seaside bluffs. His routing highlights the property's best assets, alternating between linksland and forest before bursting out onto the Pacific Ocean on Nos. 15-17. Throughout, MacKenzie and Hunter's artistry matches the beauty of the land. Their smallish greens emerge naturally from the terrain, and their ragged-edged bunkers echo the gnarled shapes of the surrounding dunes and trees. This wildness has been tempered over the years by maturing vegetation and refinements in maintenance, but Cypress Point is still one of the most overwhelming golf courses in the world—the product of an all-time great architect getting his hands on an all-time great piece of land.

Take Note...

A free glimpse. Many golfers spend decades yearning for a tee time at Cypress Point. Anyone, however, can use the hiking trails that vein the Del Monte Forest. One of these, the “Green” trail, happens to run along the dune ridge above the sixth, seventh, and eighth holes at Cypress Point. The trail then takes a right turn and wraps around the third and fourth holes at Spyglass Hill Golf Course. Here's a map. I would also recommend spending some time at Fanshell Beach, which sits within shouting distance of Cypress's eye-catching 13th green.

MacKenzie's champion. Only in recent years has Marion Hollins started to receive proper recognition for her contributions to California golf and the game in general. As the athletic director for Samuel F.B. Morse's Del Monte Properties, she hired Alister MacKenzie for the Cypress Point job and gave critical input into the design of the famed 16th hole. Later, Hollins teamed with MacKenzie in developing Pasatiempo Golf Club in Santa Cruz, California. At the opening celebration for that course, she introduced MacKenzie to Bobby Jones, who soon tabbed MacKenzie to design a St. Andrews-inspired “inland links” on the site of the former Fruitland Nurseries in Augusta, Georgia.

Raynor Point? Seth Raynor, the architect behind Chicago Golf Club and Fishers Island Club, was Marion Hollins's initial choice to build Cypress Point. In February 1925, he created a rough routing plan for the course, but just under a year later, he died suddenly of pneumonia. For decades, golf architecture enthusiasts have wondered whether Raynor deserves partial credit for the design. Soon they won’t have to wonder anymore. Sometime after the 2025 Walker Cup at Cypress Point, the club will publish David Normoyle’s centennial history book. This book will contain a reproduction of Raynor’s plan and a fine-grained comparison between Raynor’s and MacKenzie’s efforts.

{{content-block-course-profile-cypress-point-club-001}}

Favorite Hole

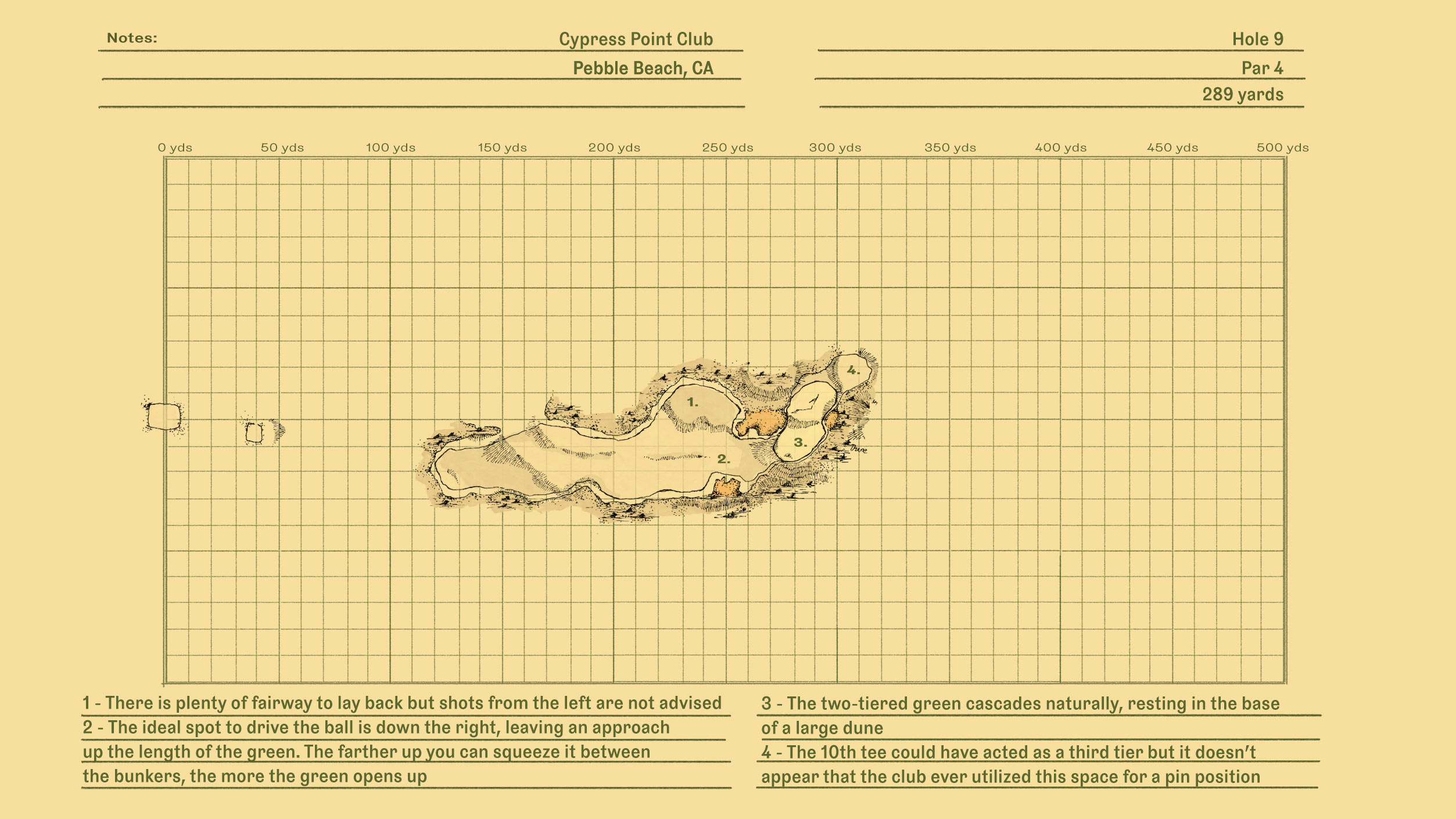

No. 9, par 4, 292 yards

Draped across the top of a dune ridge, this little par 4 is one of the most beautifully sited golf holes in the world. The tee shot plays downhill to a fairway tumbling over sandy humps and hollows, and the short approach climbs back up to a green nestled into the upslope of a large, abrupt dune. This is one of the most striking pieces of inland terrain that golf has ever occupied.

The hole is just as beguiling strategically as it is aesthetically. From the back tee, a 180-yard shot is a safe option, leaving about 110 yards to the pin. The green is so skinny and severely tilted, though, that players will be motivated to earn as short an approach shot as they can. This is where danger enters. The longer you hit your tee shot, the greater the chance you will find the sandy waste on either side of the fairway.

An additional wrinkle: the fairway provides plenty of space on the left about 45 yards from the green, making a 240-yard shot down the left side a viable play. The problem is, the pitch from this spot—blind, over a gaping bunker, from an angle that makes the green very shallow—is one of the most intimidating imaginable. If you don’t chunk it, you’re a stronger person than I.

Favorite Hole

No. 9, par 4, 292 yards

Draped across the top of a dune ridge, this little par 4 is one of the most beautifully sited golf holes in the world. The tee shot plays downhill to a fairway tumbling over sandy humps and hollows, and the short approach climbs back up to a green nestled into the upslope of a large, abrupt dune. This is one of the most striking pieces of inland terrain that golf has ever occupied.

The hole is just as beguiling strategically as it is aesthetically. From the back tee, a 180-yard shot is a safe option, leaving about 110 yards to the pin. The green is so skinny and severely tilted, though, that players will be motivated to earn as short an approach shot as they can. This is where danger enters. The longer you hit your tee shot, the greater the chance you will find the sandy waste on either side of the fairway.

An additional wrinkle: the fairway provides plenty of space on the left about 45 yards from the green, making a 240-yard shot down the left side a viable play. The problem is, the pitch from this spot—blind, over a gaping bunker, from an angle that makes the green very shallow—is one of the most intimidating imaginable. If you don’t chunk it, you’re a stronger person than I.

Overall Thoughts

When historians speak of the “Golden Age of golf architecture in America,” they are usually referring to the years between the opening of C.B. Macdonald’s National Golf Links in 1911 and the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. If we take a transatlantic view, we might mark the beginning of this era earlier—perhaps 1900, when John Low and Stuart Paton dug a pair of center-line bunkers in the fourth fairway at Woking Golf Club; or 1901, when the first course at Sunningdale Golf Club opened. In any case, it was during the first three decades of the 20th century that architects like Harry Colt, Tom Simpson, Donald Ross, Seth Raynor, A.W. Tillinghast, William Flynn, George Thomas, and Alister MacKenzie honed their craft and produced almost all of their best work.

With the building of Cypress Point Club in 1927 and 1928, the Golden Age reached its apex. MacKenzie’s and his team’s efforts on this project represented the culmination of two decades of progress in golf course design and construction. Cypress Point could not have been built to the same standard either 10 years prior or 10 years later. It was uniquely excellent, and it remains so.

Here are three key innovations of the Golden Age that Cypress Point exemplifies:

1. Routing. During the first three decades of the 20th century, golf architects became far more sophisticated in how they routed golf courses. They moved beyond the out-and-back structures of early links courses to discover a variety of complex ways to arrange holes and maximize landforms.

MacKenzie’s routing of the first 14 holes at Cypress Point is a fine example of this advance in Golden Age golf architecture. The inland portion of the property has one outstanding feature: a massive dune ridge, roughly forming a triangle. In his revision of Raynor’s initial routing, MacKenzie focused on locating more greens and tees—nine and eight, respectively—on or near this geological wonder. Of the 14 inland holes at Cypress Point, only one, No. 5, sits completely in the forest at the east end of the site; every other hole connects with the dunes in some way. Nos. 7, 8, and 9 even vault to the top of the ridge—a daring move that Raynor apparently did not attempt.

{{cypress-point-dunesy-gallery}}

In its varied and creative use of the natural landscape, MacKenzie’s routing of Cypress Point embodies the best practices of Golden Age golf architecture.

2. Strategic design. Rather than designing holes that simply punished poorly struck or wayward shots, many Golden Age golf architects sought to create risk-reward scenarios that tested players’ minds as much as their swings. This approach came to be known as the “strategic school” of golf course design.

MacKenzie was a passionate proponent of the strategic school, and Cypress Point proves as much. Several holes feature diagonal hazards off the tee: on No. 2, a rocky ledge; on Nos. 8, 12, and 13, dunes and sandy waste; on No. 17, the Pacific Ocean. In each case, players must decide how much risk to take on. Those with the courage and skill to carry the long side of the hazard are rewarded with a shorter approach from a better angle. However, players who choose the conservative route, whether by choice or necessity, can make up ground just by staying safe. For MacKenzie and other Golden Age architects, this was a key benefit of strategic design: the weak but smart player could tack his way around the course, gradually wearing down a strong but reckless opponent.

{{cypress-point-carry-gallery}}

3. Construction. By the late 1920s, the top Golden Age golf architects had become deeply knowledgeable about the art and science of construction. Trial and error—including agronomic disasters at high-profile projects like National Golf Links and Pine Valley—had yielded many useful lessons. At Cypress Point, Alister MacKenzie and Robert Hunter applied those lessons with remarkable expertise.

MacKenzie and Hunter’s company, the American Golf Course Construction Company, headed up the building process. On-site leaders included Hunter’s son, Robert Jr., Jack Fleming, Dan Gormley, Paddy Cole, and Michael McDonagh—all talented and experienced builders. This team was able to make many alterations to the terrain quickly and cheaply. They cleared 35 acres of trees, harvested sand from the dunes and spread it through the other sections of the course, installed a state-of-the-art underground irrigation system and drainage network (“a novelty in those days,” MacKenzie expert Joshua Pettit told me), constructed irrigated walking paths and multiple alternative tee boxes, and, by MacKenzie’s own admission, “artificially created” every bunker and “artificially contoured” every fairway and green. By the standards of the 1920s golf course construction, this was not a minimalist undertaking. Yet MacKenzie, Hunter, and the American Golf Course Construction Company finished everything in about six months and for a total of $90,000—40 percent under the initial bid.

Just as impressive as their efficiency was their artistry in covering their tracks. Cypress Point is, in my opinion, the most exquisitely shaped course of the Golden Age. The manufactured features tie in seamlessly with the surrounding landscape. The bunkers are dazzling works of landscape art, echoing the shapes of the dunes and cypress trees while retaining their own sculptural integrity. As MacKenzie put it (with evident pride but little exaggeration), “The world’s greatest artist would find it impossible to tell where nature ended and artificiality commenced.”

At Cypress Point, the right piece of land met the right moment in history and the right developers, architects, and builders. Place, time, and people aligned. The result was a marvel.

3 Eggs

Was there any doubt about this rating? On the strengths of its land and design alone, Cypress Point would reach three-Egg status. The course’s presentation is outstanding, too, but not quite world-beating. Over the past century, the club has been conservative in its stewardship of MacKenzie’s design. The course has never undergone a significant renovation. Since the early 2010s, Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw have guided the club through some historically informed projects, restoring bunkers and expanding greens. This gradual approach has allowed Cypress Point to continue feeling like a product of the Golden Age (a welcome rarity in our era of top-to-bottom reconstructions), but there is still work to be done. Many of MacKenzie’s original greens were slightly bigger than today’s versions, and his bunker edges more intricately detailed. I would love to see these nuances recaptured. It would be silly, though, to linger too long on such nitpicks; Cypress Point is already my favorite golf course in the world.

Course Tour

Note: We'll be on-site at the Walker Cup and photos will be updated throughout the weekend.

Additional Content

Deep Dive: Cypress Point (Designing Golf Podcast)

2025 Walker Cup at Cypress Point with Geoff Shackelford (Fried Egg Golf Podcast)

Cypress Point | Site of the 2025 Walker Cup Match

Leave a comment or start a discussion

Get full access to exclusive benefits from Fried Egg Golf

- Member-only content

- Community discussions forums

- Member-only experiences and early access to events

.webp)

.webp)

Leave a comment or start a discussion

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere. uis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.