A few years ago, before becoming the architect of an internet-famous backyard golf course called Brough Creek National, Ben Hotaling was another twentysomething who hadn’t played golf in a while. He had competed on his high school team but had drifted away from the game while attending the University of Kansas. “I just had no money or country club to play at,” Hotaling says. “It was hard to get all the friends together to go buy a round.”

After graduating in 2015, he moved in with his friend Zach Brough, who lived on three-and-a-half acres of forest outside of Kansas City, Missouri. Hotaling, whose interest in golf had begun to stir again, saw an opportunity.

“I just asked Zach if I could dig a bunker and take down one tree to open up a 115-yard shot. He was down, so we went with it.”

The project came together quickly. Hotaling bought a tiki torch to use as a flag, and as soon as he and his friends chopped down the tree, they started playing the hole. “It was super easy and fun,” he says.

For most people, it would have been neither easy nor fun. But this wasn’t Hotaling’s first backyard construction project. “I was the kid that was always outside digging holes, building forts, and constructing trails for my dirt bike,” he says. As a teenager, he lived on big piece of land where he and his dad cleared seven acres for a horse paddock. He hit some golf shots out there as well.

After some refinements and a lot of laps with the push mower, the hole on Zach Brough’s property looked great: rustic yet well shaped, framed by native grasses, and guarded by a bunker on the right and a creek—“Brough Creek”—on the left. After hundreds of plays, the hole revealed some eccentricities. “It’s very deceptive,” Hotaling explains. “You need to hit your shot just over the top of the bunker for it to get close. It will bounce different every time.”

The original hole at Brough Creek National. Photo credit: Ben Hotaling

Hotaling admits, however, that not much critical thought went into the design. “At the time, I knew nothing about architecture.”

The Founding of Brough Creek National

When Hotaling got back into golf after college, his interests initially revolved around finding new equipment to improve his game. He followed club makers and reviewers on Instagram, and he subscribed to Rick Shiels’s YouTube channel. Then, in late 2016, a friend introduced him to The Fried Egg podcast. He listened to episode 7, an interview with architect Keith Rhebb, and found himself intrigued.

Learning about golf course design changed Hotaling’s attitude toward the game. “It opened my eyes to the fact that golf is more than shooting low scores,” Hotaling says. “I realized that golf was meant to be fun, and learned that there is a reason I like and dislike courses.”

He also began to rethink what could be done on Zach Brough’s land. Instead of just one 115-yard shot, Hotaling envisioned a pitch-and-putt course moving up and down the central ridge, along and across Brough Creek. He imagined holes that paid tribute the 17th at St Andrews and the 12th at Augusta. Yes, a lot of trees would have to be removed, but something cool—something functional as well as architecturally compelling—could be built here, in his buddy’s backyard.

Hotaling and his friends figured it was time to form a club. They called themselves Brough Creek National, a cheeky allusion to their sister institutions at Augusta and Hazeltine.

In May 2018, Hotaling brought his ideas to The Refuge, No Laying Up’s message board. He found an enthusiastic audience. His thread, “Armchair Architect Needed: Help design backyard wedge range,” is now more than 800 comments long. “People really seemed to like it,” Hotaling says, “and that gave us energy.”

Interest ramped up further in October, when Hotaling started handing out free memberships to Brough Creek National, complete with a mailed letter and a logoed poker chip. A brand identity—Some Guy’s Backyard—soon followed, along with a Twitter account and a website. To date, Brough Creek National has 450 members.

The Brough Creek National poker chip and barn. Photo credit: Ben Hotaling

This inclusive approach is part and parcel of a philosophy that Hotaling developed through learning about the history of golf course design. The game’s roots were in communities that decided, for the benefit of all, to lay out natural courses on common land. These courses rarely had 18 holes or a par of 72, and their fairways and greens were hardly ever green and smooth, but they were fun to play, cheap to maintain, and, above all, accessible to everyone, sometimes for free.

With Brough Creek National, Hotaling is testing the hypothesis that modern American golfers long for raw, offbeat, and inclusive places to play. “We think fun, unconventional golf courses can still be built using minimal resources,” he writes on the Some Guy’s Backyard website. “More excitingly, we think we can offer communities the ability to play golf for free.”

That last word—free—is the one that brings a lot of golfers up short. In opposition to the exclusive country clubs and expensive daily-fee courses that kept Hotaling and his friends away from the game in college, Brough Creek National does not plan to charge people anything either to join or to play. Members are simply invited to make a spontaneous contribution, whether in the form of goods, services, or cash.

Earlier this month, Some Guy’s Backyard tweeted out a course plan. Drawn by architect Colton Craig, it depicts seven crisscrossing holes ranging from 58 to 116 yards. The second, with its Road bunker and its tee shot over a barn, and the fourth, with its Biarritz-inspired sliver of a green, are particularly intriguing.

The Brough Creek National routing map. Credit: Colton Craig

Ambitious as this design might seem, it won’t require much earthmoving, according to Hotaling: “You would have to see it in person to understand how perfect the size of the green and tee areas are for what we are building.” That said, he and his team, which includes Zach Brough and their friend Corbin Mihelic, may push some dirt around in order to accentuate the undulations that the property already has. “Since we will have basically short-cut fairways for greens,” Hotaling explains, “I want to have some pretty drastic features on the greens. This will allow every element of putting and short game to play a part.”

So far, the Some Guy’s Backyard crew has taken down hundreds of trees and cleared out several tee and green areas. They plan to seed and shape the course in the spring and have it ready for an opening event on September 1 of this year.

Building a golf course is one thing; keeping it playable is another. But Hotaling has a plan for that as well. “Brough Creek National will have conditions that require no more maintenance than it would to manage the backyard,” the Some Guy’s Backyard website states. “Prepare to see more shades of brown and tan than emerald and lime green. The goal is to have the ability to fill in the bunkers, take out the flags, and have the property look like the course was never there.”

The "road bunker" at Brough Creek National. Photo credit: Ben Hotaling

Pasture Golf in America

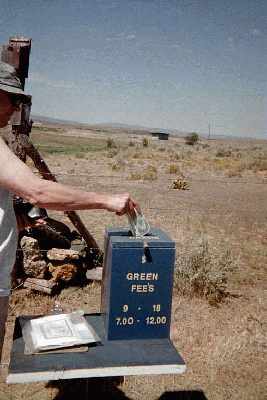

Ben Hotaling and his friends are hardly the first Americans to take inspiration from old Scottish design. All over the country, on the outskirts of small towns or across open ranges or in random guys’ backyards, there are golf courses that sit lightly, even almost invisibly on the landscape. Courses that were more “laid out” than they were “built.” Courses that receive only the most basic maintenance and that take on seasonal hues, sometimes brownish ones. Courses that you can play for two bucks dropped in an honesty box, or for a six-pack delivered to the proprietor, or for nothing at all.

In the late 1990s, an Oregonian named Bruce Manclark began cataloguing these kinds of places. He called them pasture golf courses. On his website, pasturegolf.com, he described their common traits—a literal pasture is optional, for one—and he profiled several of them. For a few years, he helped organize a group road trip, referred to alternately as “the Pasture Golf Tour” and “the Northwest Highland Golf Tour,” that visited courses in the remote Oregon towns of Seneca, Christmas Valley, Condon, and Fossil.

Kinzua Hills Golf Club in Fossil, Oregon. Photo credit: 1859 Magazine

Not all of the courses featured on pasturegolf.com accepted Manclark’s label. “Unfortunately,” he says, “some people took ‘pasture golf’ as a demeaning term, but it wasn’t meant that way.”

Indeed, the website is nothing if not a celebration of the grand history and enduring ethos of pasture golf. “Golf has not always been a trendy sport, restricted to monied elites,” the homepage reads. “At its birth it was the game of a rural people, played simply on the fells and fields where sheep and cattle grazed. Pasture golf celebrates the undercurrent, the backwash maybe, that returns to these grassroots.”

The website has not been updated in several years. Speaking about pasture golf now, Manclark often slips into the past tense. The courses still exist; he just sees his advocacy of them as belonging to another era.

“Pasture golf was a counterbalance to the golf course boom that was happening,” Manclark says, referring to the late 1990s and early 2000s. “It was a reaction to really expensive courses—and probably equipment technology, too. We were trying to point out that golf is enjoyable on non-manicured courses. And it’s usually more affordable, and it’s usually easier on the environment. It was the analog response to artificial golf courses.”

Now, though, with course closures far outpacing course openings, and with minimalist golf architecture gaining popularity, the notion of pasture golf has lost some of its urgency for Manclark. But he still visits those rustic courses in the Oregon highlands on occasion. “It’s fun to go out and have this little money lockbox,” he says, “and if you want to play, you leave a little bit there.”

The lockbox at Bear Valley Meadows Golf Course in Seneca, Oregon. Photo credit: Bruce Manclark

Pastures New

For a rising generation of golf enthusiasts, however, the allure of the pasture seems to have returned. Blake Conant, a young architect who has worked for Tom Doak’s Renaissance Golf Design as a shaper, has studied pasture golf for years. In graduate school at the University of Georgia, he and his roommates charted out a six-hole loop on a parcel behind their apartment building. He even did a project for one of his classes on whether the land would be suitable for golf development.

Today, on his massive digital map of courses he wants to see, Conant has included a number of specimens of pasture golf. “This is probably how golf courses started 600 years ago,” he says.

As we approach the 2020s, a renewed yearning for pasture golf would make sense. Overall, golf is contracting. Courses are closing, fewer people are playing, and the game is becoming less accessible—or at least less accessed. At the same time, golf architecture has seen a revival. Private clubs are ponying up for restorations of Golden Age designs, and destination resorts are extracting top dollar for rounds at courses built by the leading architects of the day. Also, appreciation of golf course design has reached what must be an all-time high, thanks to the way the internet and social media have spread knowledge and shaped tastes.

The result is that there are now legions of golf architecture aficionados, but they have little opportunity to visit the courses that most fascinate them. To this population, the appeal of a Brough Creek National—an intelligently designed, naturalistic course, open to all and free to play—is obvious.

Unadorned courses in backyards and pastures also pose a useful challenge to current trends in golf architecture. By now, the term “minimalism,” once used to describe the efforts of Coore & Crenshaw and Tom Doak to move as little earth as possible, has been stretched beyond recognition. In a recent Golf Digest article, Ron Whitten claimed that Congaree, a new course for which Tom Fazio created “hills, ridges and lakes,” represents “the grand tradition of minimalist architecture” because “the hills and ridges are massive enough to look natural.”

If that’s what minimalism is now, the limitations of pasture golf course design could offer a necessary reality check. They could even, according to Blake Conant, provoke greater creativity.

“The option to move dirt to make it what you want isn’t there,” he says, “so you have to work within these constraints to come up with a unique idea. And then it becomes up to the person who’s routing the course. I think that’s one of the reasons the courses in Scotland came out so well. They were created by a group of guys who just went out on a piece of land and started hitting golf shots. Then somebody would say, ‘Hey, let’s put a green there.’

“Some of the best ideas come when you have a blank canvas, but you have a very strict set of guidelines to work with.”

The trouble is, in golf course design, the quality of the canvas is crucial. Advocates of American pasture golf refer frequently to the Scottish model—and with good reason. Anyone curious about affordable, lay-of-the-land golf would be remiss not to study how the old seaside links came to be, how they were maintained, and how they served their communities. Yet the Scots of the 18th and 19th centuries had a key advantage over us: plenty of public land ideally suited to the game. On rolling, sandy terrain covered in rabbit-tended fescue, rudimentary architecture and a small maintenance budget work well. But on the kind of land that would be made cheaply available for golf in the 21st century? Perhaps not so well.

Those are the challenges that Some Guy’s Backyard has decided to confront—both in molding Brough Creek National out of Kansas City clay and in tackling whatever comes next. Ben Hotaling is willing to entertain the prospect of taking Some Guy’s Backyard on the road and staking out quirky courses in far-flung pastures. “I’d like to prove that unconventional golf focused on fun has a place in the game,” he says. “I’d love for Some Guy’s Backyard to have an impact by providing that option for golfers.

“We are using Brough Creek National to gain all the knowledge we need to pull something like this off. I’m just not sure where it will take us yet.”

In the meantime, Hotaling is puzzling over the next construction task. There are more trees to cut down, and these ones are in tricky positions on the side of a ridge, where they could fall in dangerous ways. Hotaling and his friends are not experts on tree removal, but they have access to all the information they need, and they believe that, for a few days in late January, they can become lumberjacks. Given that they have already become designers, developers, and club organizers, why not?

by

by