The natural terrain of coastal Southern California seems to call out for golf. Some of the landforms appear to have already arranged themselves into fairways, greens, and bunkers. The valley floors have good undulation, and the hills are veined with river courses that, for most of the year, remain dry. Native trees grow in irregular copses that enhance golf strategy, not in dense forests that constrict it. The ground is covered in a type of scrub known as chaparral, which has put more than one British visitor in mind of gorse.

Combine this rugged landscape with a semi-arid climate, and you have one of the best settings in the world for golf. California-based architects of the 1920s and 30s—Norman MacBeth, Max Behr, Alister MacKenzie, George Thomas, and Billy Bell—recognized this fact, and they honored the land by leaving it more or less untainted. Sadly, many of their courses perished in the mid-20th century, buried under postwar development in the Greater Los Angeles and San Diego areas.

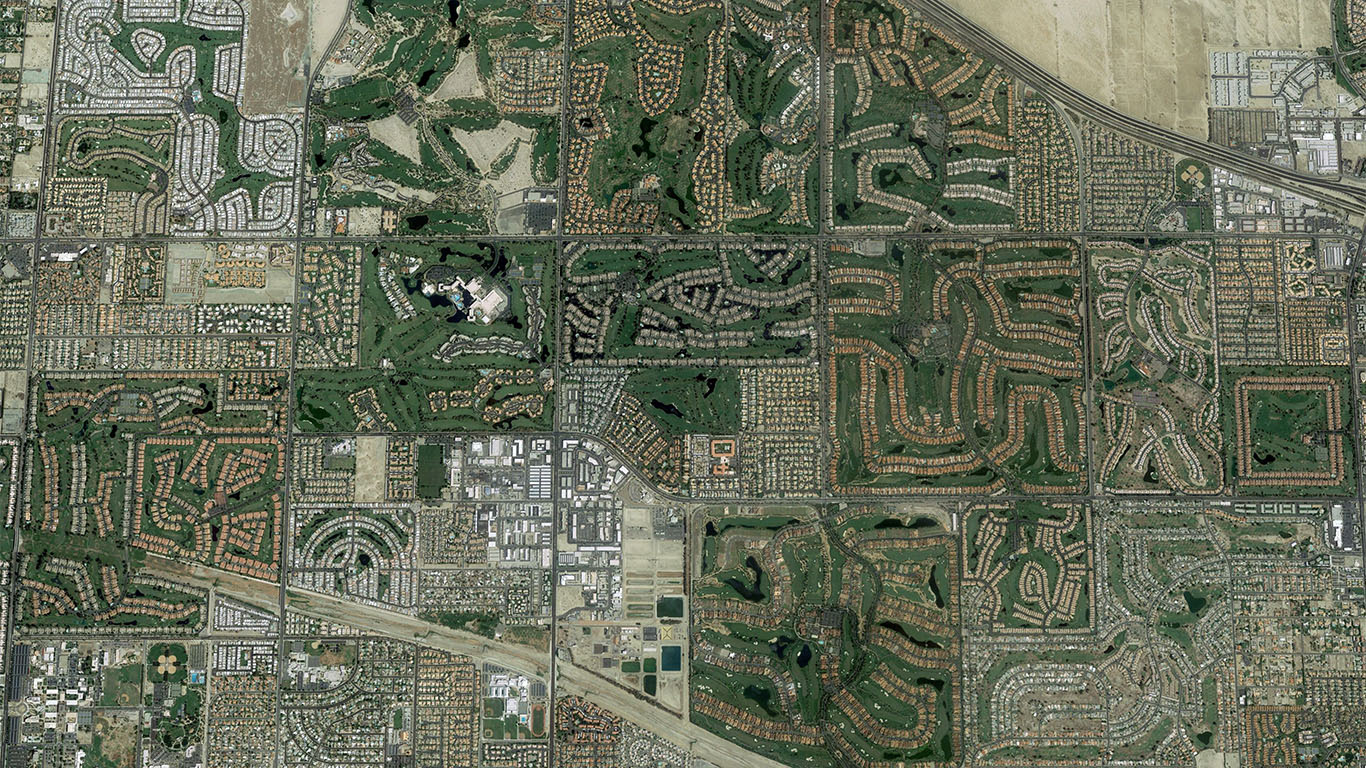

In the 1980s and 90s, Southern Californians took a renewed interest in golf, but not in a version of the game that Thomas and Bell would have recognized. The courses being built were less golfing grounds than components of housing developments. In the desert of the Coachella Valley, architects like Pete Dye, Jack Nicklaus, and Arnold Palmer routed holes between monotonous rows of bungalows. Even on better properties closer to the coast, SoCal courses tended to ignore playability and walkability in favor of resistance to scoring, cart-path access, and signature-hole pyrotechnics.

Squares of development golf in Palm Desert, CA. Google Earth, 2018

Not all of those courses were bad. Few, however, had a true sense of place.

Architects bulldozed natural ground contour into level fairways and containment mounds. They turfed over shrubland. They trucked in pines and palms to replace native oaks and sycamores. Instead of routing holes around barrancas, architects manufactured ponds, creeks, and waterfalls, some of which came with electric pumps to ensure a luxurious flow of water in times of drought. These courses appear to take no joy in their surroundings. They yearn, it seems, to be anywhere else: Georgia, or Connecticut, or the Las Vegas Strip.

It was in this milieu that, in 1999, a tract of county-owned land became available in Moorpark, California, 50 miles northeast of downtown Los Angeles. The property centered on a sandy, scrubby canyon, and the lease allowed for the construction of a “moderately priced” public golf course. The buyer reached out to the writer Geoff Shackelford, who in turn got in touch with the architect Gil Hanse. Together, Shackelford and Hanse would create a new—yet old—kind of Southern California golf course.

The discovery of Rustic Canyon

Few developers saw potential in the land, in spite of its beauty. As Shackelford told The Fried Egg, “There weren’t a lot of people interested in developing a golf course with the restrictions that you would have on county-owned land.”

Shackelford and Hanse, however, did not find such restrictions as bothersome as others did. They had no desire to violate protected landforms or even to alter the terrain much at all. “During various meetings with local agencies,” Shackelford wrote in his book Grounds for Golf, “I soon learned that the lack of earthwork was key to selling the course to the strong environmental movement working to preserve Ventura County’s many beautiful areas.” In fact, Shackelford’s main challenge was convincing environmentalists that he and Hanse were for real. “They didn’t believe that we literally intended to mow down the corridors of most of the holes,” he said to The Fried Egg. “And I don’t blame them. They’d seen things built with mounds and blinding bunkers.”

In early 2001, the design team, headed by Hanse himself and his partner Jim Wagner, got to work on what would become Rustic Canyon Golf Club. True to their word, they discovered the course more than they built it. The basic shape of the par-5 1st hole, for instance, was already there. The sandy scar that splits the corridor in two is an old earthquake fissure. “It looked like an abandoned hole,” Shackelford said. “It was that good.”

-

The 1st hole at Rustic Canyon

-

The 1st hole at Rustic Canyon

-

The 1st hole at Rustic Canyon

-

The 1st hole at Rustic Canyon

The same was true of the par-4 16th, which plunges from a high tee on the western hillside above the canyon. The fairway runs through a natural saddle down to a bunkerless green.

-

The 16th hole at Rustic Canyon

-

The 16th hole at Rustic Canyon

-

The 16th hole at Rustic Canyon

-

The 16th hole at Rustic Canyon

Finally, the best feature of the property, the dry channel that cuts through the center of the valley, remains beautifully intact. On several holes, it serves the simplest function in strategic design. Place your ball near it and earn an advantage; hedge away from it and, on the next shot, pay the price of your comfort.

-

The central river course at Rustic Canyon

-

The central river course at Rustic Canyon

-

The central river course at Rustic Canyon

-

The central river course at Rustic Canyon

The light touch of Hanse Golf Design resulted in a course with a layered, specific sense of place. When you walk Rustic Canyon, you can feel the Southern California landscape all around you: the sand, the chaparral, the rippling topography, the sudden profusions of pepper trees. You can also sense the rattlesnakes—if not with your eyes or ears, at least with your imagination.

Rather than altering the essence of this place, the golf course offers a new way to enjoy it.

The legacy of Rustic Canyon

“When Rustic first opened in 2002,” Tommy Naccarato told The Fried Egg, “people said, ‘It’s different than anything we’ve ever seen.’” Naccarato was on site during the construction of the course, doing, as he put it, “a little bit of everything.” He is now a member of the Hanse Golf Course Design staff. “And I’m sitting there,” he continued, “and I’m going, ‘No, no, you don’t understand. This is what we had at one time.’ You’re standing on the fairways [at Rustic Canyon], and you’re looking at a very similar scene as what Riviera used to be.”

Rustic Canyon was not the first modern American course to have an authentic sense of place and a flavor of classic design. By 2002, plenty of Southern Californian golfers would have been aware of Sand Hills Golf Club, Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw’s 1995 lay-of-the-land masterpiece in Mullen, Nebraska. They would also have known of the excitement over David McLay Kidd’s and Tom Doak’s wild layouts at Mike Keiser’s new resort in Bandon, Oregon. Unlike Sand Hills and Bandon Dunes, however, Rustic Canyon was near a massive population center, and it was conceived as an affordable public course for the common golfer.

That meant it faced an unusual amount of scrutiny from the get-go. Reviews were mostly positive, even glowing, but Shackelford remembers the nitpicks. “The first year or two, we’d always get this: ‘You know, it’s a fun course.’ That was code for ‘it’s nice, but it’s not championship quality.’” Other targets of critique included the long walks to a few tees, the divergent characters of the two nines, and the fact that “you could just hit a bad shot and putt from anywhere!”

Today, these are among the very reasons golfers adore Rustic Canyon and go back again and again. It helps, too, that superintendent Jeff Hicks has stayed faithful to the course’s founding principles, maintaining firm turf that’s fun to play on and doesn’t always try to be green.

Through the 2000s, as Rustic Canyon’s reputation grew, golf architecture in Southern California changed. New construction slowed down, and many of the artificial courses of the 80s and 90s were struggling or closing. Meanwhile, older private clubs began to rediscover what they once had. At Wilshire Country Club, the Valley Club of Montecito, and Los Angeles Country Club, restorations by Kyle Phillips, Tom Doak, and Gil Hanse, respectively, reintroduced a Southern Californian ruggedness to some of the great designs of the Golden Age of golf architecture.

“There’s now a love of embracing what is native to California,” Shackelford said, “and it’s fantastic. I think locally [Rustic Canyon] was definitely a big part of that movement.”

In another sense, though, Rustic Canyon remains a unicorn: an affordable, minimalist, strategically sophisticated 18-hole public golf course built by a celebrated architectural firm on an well-suited piece of land. Since 2002, have we seen anything else like it?

The 5th green at Rustic Canyon from behind

Tommy Naccarato doesn’t think so. He looks back on his days at the Rustic Canyon construction site with a measure of sadness. Once, he sat for three straight hours and watched Gil Hanse shape the bold, exquisite contouring left of the 5th green.

“It represents a purity that we will never, ever get to see again,” Naccarato says. “Unless somebody steps up.”

Sign Up for The Fried Egg Newsletter

The Fried Egg Newsletter is the best way to stay up to date on all things golf. Delivered every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday for free!

by

by