Golf course architecture can be an intimidating subject to get into. Here at The Fried Egg, we’ve thought a lot about how to introduce concepts like routing, strategy, and aesthetics without confusing or frustrating readers right off the bat. One thing we’ve discovered is that the “ideal holes” of C.B. Macdonald and Seth Raynor can serve as an approachable way to get into more advanced subjects. “Templates” like the Redan, the Biarritz, and the Double Plateau are easy to understand, and they embody principles of design that many great courses share. Also, since Macdonald and Raynor had an affinity for big, bold bunkering and contouring, their intentions tend to show up clearly on maps and in photos. So National Golf Links, for instance, can function as a kind of textbook, a readable introduction to golf course architecture.

But there’s a problem with using Macdonald and Raynor’s designs in this way: most golfers can’t play them. The only public-access Macdonald and Raynor course is the Old White TPC at the Greenbrier, where the peak-season green fee for non-guests is $495 (not including the required forecaddie). Seth Raynor’s solo work, which comprises 40-some courses in North America, isn’t much more accessible. He may have had a hand in the public, affordable Thousand Islands Country Club in Upstate New York, but that course no longer resembles a genuine Raynor design. Almost all of his other courses belong to private clubs.

Almost.

On May 11, 2019, Rock Spring Golf Club opened its doors to the public for the first time in its 93-year history. Rock Spring is in West Orange, New Jersey—15 miles west of lower Manhattan—and it was designed by Seth Raynor in 1925. After Raynor died in January 1926, his associate Charles Banks built the course.

An aerial photograph of Rock Spring Country Club, circa 1940

Rock Spring made it through the Great Depression, but the Great Recession was too much. In 2019, the township of West Orange bought the property, and suddenly the golf world had its first Seth Raynor-designed municipal course. For a simple green fee, anyone could go see and study Raynor’s “ideal holes” in a real, three-dimensional environment. Right away, Rock Spring became one of the golf architecture community’s most important resources.

But most people in West Orange didn’t expect the course to survive much longer.

◊

For its first several decades, Rock Spring led a peaceful existence as a mid-tier club in the New York City suburbs. The course’s architecture decayed in the usual ways: trees were added, bunkers lost, fairways narrowed, greens shrunk. But most of the template holes were still recognizable, and the basics of Raynor’s design and Banks’s construction remained intact.

Rock Spring in 1995 (Google Earth)

Then, in 2001, the club hired Ken Dye (no relation to Pete) to renovate Rock Spring’s bunkers. Dye is well regarded for his daily-fee designs in the Southwest—including Piñon Hills and Paa-Ko Ridge in New Mexico—but his projects at historic golf courses haven’t garnered as much praise. At Rock Spring, he introduced a set of oval-shaped, flashed-up bunkers that looked nothing like Raynor and Banks’s original grass-faced trenches. The members presumably signed off on this work, but they weren’t pleased with the results. Just five years later, they hired Kelly Blake Moran to overhaul the bunkers again.

-

Rock Spring in 2007, after its bunker renovations (Google Earth)

-

Some renovated bunkers as they stand today on the 11th hole at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

The expense of back-to-back renovations, combined with the loss of some frustrated members, put the club in a precarious financial position. Then the recession hit. By the early 2010s, Rock Spring was around $4.5 million in debt, and the property started to change hands. Nearby Montclair Golf Club purchased it in 2016 and attempted a merger. That experiment didn’t pan out, and at the end of the 2018 season Montclair closed down Rock Spring and put it up for sale. The likeliest outcome was that a developer would step in and turn the site into a residential neighborhood.

But this turned out to be an unpopular idea in West Orange. Townspeople valued the open space that the golf course provided, and they didn’t want more development, traffic, and population. So in early 2019, the township council agreed to purchase Rock Spring for $12 million and run it as a municipal course for at least a couple of years.

Word of this deal made its way to Steve Lesnik, who had grown up in the neighboring town of South Orange. Lesnik is the chairman of KemperSports, a golf course management company, and he put in a bid to operate Rock Spring. When Kemper won the job, Chris Parker was installed as the course’s general manager.

“Right away,” Parker says, “you could just tell it hadn’t been touched for a long time.”

◊

Chris Parker and his team spent a few weeks just reclaiming fairways and greens. Brandon Ramage, a young graduate of the turf program at Delaware Valley University, came on as head superintendent, and his first task was simply to make the course functional again.

Rock Spring opened in the second weekend of May 2019, but there was still a lot of work to do. There were many soggy spots, and sometimes, when Parker and Ramage dug down to investigate, they would find an old drain inexplicably covered with concrete. Some mornings, they would show up and find that one of Ken Dye’s ovals had caved in overnight. Yet Parker believed in the course’s potential. “We knew we had a great piece of land, great template holes, great historic designer,” he says, “but it just needed some TLC.”

Behind the 1st green at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

Meanwhile, Rock Spring’s future remained uncertain. KemperSports had signed an 18-month contract with West Orange, and township leaders had indicated that this was, at best, a trial period. They considered various proposals for the property, including ones that involved reducing the golf course to nine or 12 holes and selling off a portion of the land to a developer. Some preferred to eliminate the entire course and convert it to public green space.

But Chris Parker wasn’t resigned to either of those fates. “We wanted to come in and prove to the township how special this place was,” he says, “and how successful it could be.”

As course conditions improved, rounds picked up. Even in a region that had several public courses from the “Golden Age” of golf course architecture (notably A.W. Tillinghast’s Suneagles and Charles Banks’s Francis Byrne and Knoll West), Rock Spring stood out for its dramatic hilltop site, skyline views, and well-preserved Raynor templates. Even Parker was surprised by the appetite for tee times. “It’s amazing how deep [Raynor’s] following is,” he says.

That appetite increased again last year, when Rock Spring opened after the Covid-19 shutdown. Locals flocked to the course, hungry for a relatively safe form of recreation.

Soon, West Orange abandoned discussions of cutting Rock Spring down to nine or 12 holes. In August, the township extended Kemper’s management contract to December 2026. “I don’t anticipate that the golf course will be altered to something other than an 18-hole course for the foreseeable future,” Parker says.

This past April, West Orange Mayor Robert Parisi presented a new plan for the property at a township council meeting. This plan involves selling small piece of land to AvalonBay Communities for the development of an apartment building and a parking deck. The Rock Spring clubhouse will likely be torn down and rebuilt in another location, and the 18th fairway will have to be shifted about 50 yards west, but the footprint of the golf course will not be otherwise affected.

In 2025, Seth Raynor’s 18-hole design at Rock Spring will celebrate its 100th birthday.

The 8th hole at Rock Spring, a Punchbowl template (Garrett Morrison)

◊

This golf season has been Rock Spring’s busiest yet. “Fourteen days out, we’re booked until three o’clock in the afternoon,” Chris Parker says. “We anticipated that we’d probably do 20 to 22,000 rounds a year. Now we’re on track for over 30. So you’re talking a third more. Instead of doing 100 rounds of golf a day, we’re doing around 135. Pretty impressive stuff.”

The rise in course traffic has brought some new challenges. In its days as a sleepy country club, Rock Spring did not need cart paths from tee to green. Now, with roving carts doing daily damage to the turf, Parker feels that the course needs a full set of paths. This type of project has done acute damage to the architecture at other Golden Age public courses (see: Swope Memorial in Kansas City and Balboa Park in San Diego), but Parker insists that his team will use a light touch at Rock Spring. “We’ve been real careful,” he says, “and we’ve put a lot of thought into how [the paths] would come out.”

Parker also wants to restore Raynor and Banks’s bunkers—for real this time. He has lined up Kyle Franz for the project, an architect with a deep résumé as a restoration specialist. He has restored several Donald Ross courses—including Mid Pines, Pine Needles, and Southern Pines in North Carolina—and, more to the point, he recently completed a bunker project at Raynor’s Country Club of Charleston.

The Double Plateau 14th hole (right) at Country Club of Charleston with its recently restored Principal's Nose bunker complex (Andy Johnson)

“The idea is to bring [the bunkers] back to how Raynor and Banks intended for them to play,” Parker explains. “We want to bring the faces back to how they’re supposed to be. We want you to get those optical illusions off the tee that were designed. That’s our main focus.”

The cart path and bunker work, along with some tweaks to the drainage system, could begin as early as this winter. Parker is waiting on the township’s final go-ahead, but that process, he says, “is closer to the finish line than it is to the start.”

“We’re on our way. We’ve got a lot of work to do, but we’re on our way.”

◊

Even as it stands, Rock Spring is immediately identifiable as a Raynor-Banks creation. There’s the 3rd hole, a Redan draped along the curving edge of a ravine, with a full view of the New York City skyline to the left. There’s the 4th green, a Double Plateau with sharply defined front-left and back-right sections. There’s the huge, steamshovel-shaped ledges propping up the 5th, 11th, 12th, and 15th greens. And there’s the elevated green on the Leven 10th, rimmed by a berm that both guards the putting surface and keeps water off of it. These are the kind of vintage design features you don’t see very often on public courses.

-

The Redan 3rd hole at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

-

The Double Plateau 4th green at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

-

The Road 11th hole at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

-

The Leven 10th green at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

Among the most fully realized holes at Rock Spring are the 12th and 15th, both tucked into a low-lying corner of the site. The land has a lot of slope, maybe too much to be considered ideal for golf, but Raynor and Banks made it work.

The tee on No. 12, a par-4 Bottle template, offers a clear view of the green, and the intuitive play is to aim straight at it. But if you hit your tee shot to the left instead, over the bunker in the middle of the fairway, you’ll find higher, more level ground and an easier angle down the length of the green. This is an example how Raynor used visual deception: what looks like the obvious line may not actually be the best line.

-

The 12th (left) and 15th (right) holes at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

-

The 12th hole at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

-

A ground view from the 12th tee at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

-

The 12th green at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

-

Behind the 12th hole at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

On No. 15, a Knoll hole, the challenge is again to keep your drive on the high side of the fairway, this time to the right. If you can’t hug the treeline or use a left-to-right ball flight to avoid the run-out down the hill, your approach will be uphill and directly over a deep bunker. In this way, the hole uses the natural slope of the land to create distinct options and give the short-hitting player a chance against a longer, less accurate competitor.

-

The 15th hole at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

-

A ground view from the 15th tee at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

-

The approach to the 15th green from the ground (Garrett Morrison)

-

The 15th green at Rock Spring (Garrett Morrison)

This isn’t to say Nos. 12 and 15 at Rock Spring are exactly as Banks put them in the ground. The fairway lines have crept in over the years, taking away some strategic options. Originally, the 12th fairway gave players room to steer well left of the beeline of the hole in pursuit of a better angle. Today, that side of the corridor is mostly covered in rough. The same is true of the right side of the 15th hole, where encroaching trees compound the problem. Both holes still basically work as intended, but their strategic character has been blunted.

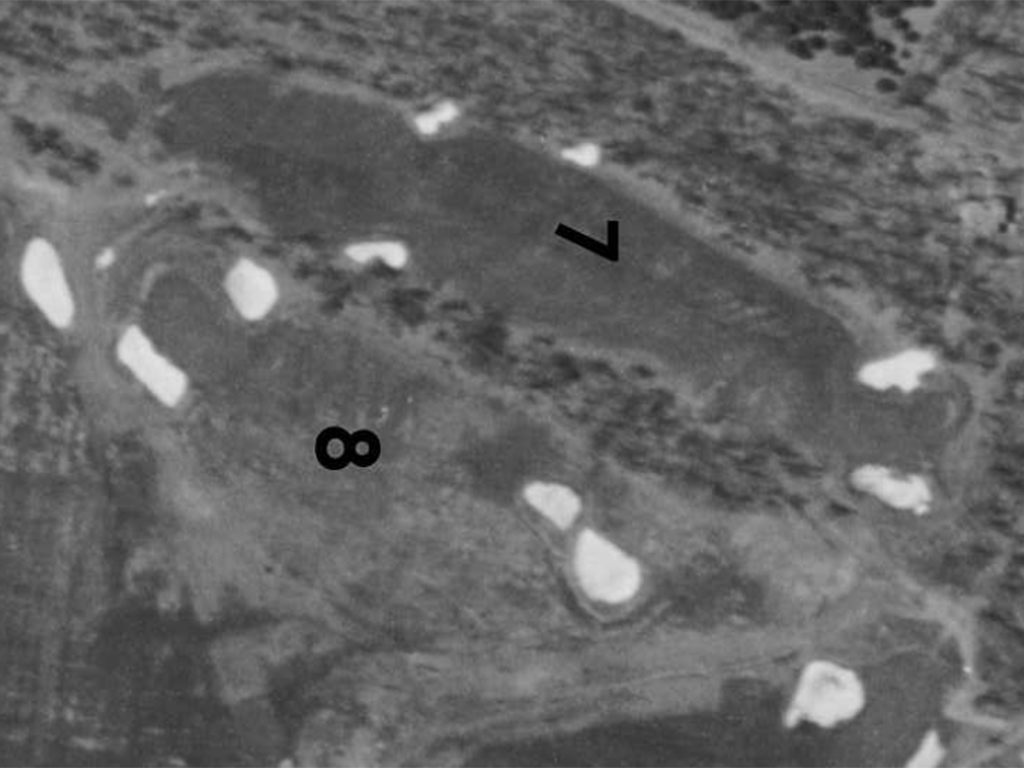

An aerial view of 7th and 8th holes (today's 15th and 12th, respectively) in 1940 at Rock Spring

These are understandable problems for a municipal facility to have. Fairway expansions and tree-removal programs are easy to suggest but tough to pay for. Besides, there are more pressing issues elsewhere on the course. Nos. 5, 13, 14, and 18 have lost many of their bunkers and around-the-green features, and have become relatively bland as a result. On many holes, deteriorating bunkers from the 2001 renovation are a daily headache. Such are the big-picture problems Chris Parker, Brandon Ramage, and Kyle Franz need to address before they start futzing with the details.

But make no mistake, Rock Spring’s excellence is not just theoretical. This is not like Griffith Park or Eastmoreland, where municipal neglect has rendered the original architecture nearly invisible. Rock Spring is an outstanding golf course right now. It’s striking to look at and fun to play—a living, accessible textbook of Seth Raynor’s design ideas.

Fortunately, the golfing public outside of West Orange seems to be catching on. “We get people from all over,” Parker says. “We get people from Oklahoma, from Texas, from North Carolina and South Carolina, just because, ‘Hey, it’s a Raynor course, and this is one I can actually get out and play.’”

by

by