The Masters has Augusta National, The Open Championship has The Old Course at St. Andrews, and the U.S. Open has Shinnecock Hills. The William Flynn design in Southampton, NY is the best U.S. Open venue the USGA has in its rota. While Oakmont and Pebble Beach are in the conversation, Shinnecock’s combination of history and masterful design put it in a class of its own.

(Photos by Jon Cavalier – @linksgems)

A historic club

Shinnecock has the claim to a couple of firsts – the first incorporated club in America and the first clubhouse in America. The club was founded in 1891 by a group of wealthy New Yorkers, including William K. Vanderbilt. One year after opening, Stanford White designed Shinnecock’s iconic clubhouse, which still stands today.

Shinnecock Hills's historic clubhouse

In 1895, Shinnecock Hills was one of the USGA’s five founding clubs along with Chicago Golf Club, Newport Country Club, The Country Club at Brookline and St. Andrew’s Golf Club (NY). Shinnecock was the flagship golf course in the epicenter of American golf, Long Island.

In 1896, Shinnecock hosted the second U.S. Open and U.S. Amateur. The club also hosted the 1900 U.S. Women’s Amateur and 1977 Walker Cup matches. This year’s U.S. Open will be the club’s fifth U.S. Open and eighth USGA Championship. But perhaps the most significant aspect of Shinnecock Hills’s history is its progressive stance on women’s golf. It has been open to women since its opening, with Janet Hoyt becoming the first female member the day the club opened in 1891.

The architectural history is also storied. The first course was laid out by little known Scotsman, Willie Davis. The original 12-hole course was expanded to 18 by Willie Dunn in 1895.

Shortly after World War I, the Long Island Railroad Tracks forced the club to redesign their course. C.B. Macdonald and Seth Raynor were hired, and their design completed in 1917. The design was filled with the pair’s signature template hole designs, also found at the neighboring National Golf Links of America.

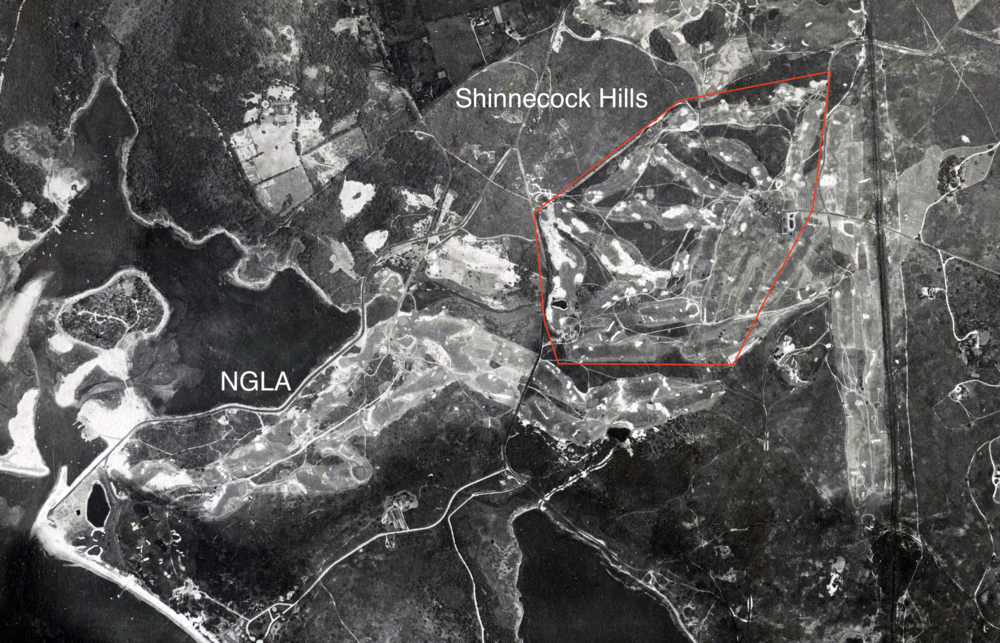

1930 Aerial of Shinnecock Hills Golf Club mid-construction and neighboring NGLA

In 1927 Shinnecock caught wind of the state’s plans to build a highway that would pass through the golf course. In response, the club purchased more land and began to plan for another redesign that William Flynn undertook from 1929-1931. Flynn kept some of the Macdonald and Raynor features on six of the eighteen holes. In 1935, a writer for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Ralph Trost, described Flynn’s Shinnecock:

“Shinnecock Hills was constructed by the same hands that built famed Pine Valley. In bunkerings and hole designs, there is much of Pine Valley suggested in Shinnecock’s holes. But Shinnecock is as open as Pine Valley is sheltered, as treeless as the NJ course is flanked by pines.”

Like most of the country’s courses, Shinnecock fell victim to tree planting, narrowing fairways and shrinking greens. Thanks to a recommendation from the USGA, the club even replaced its fescue fairways with slow and water-dependent rye grass. This all hit a precipice at the 2004 championship when the USGA lost control of the course. The rye grass and lack of water can be blamed for many of the problems. The events sounded a wake up call for the venerable club, whose golf course had slowly drifted away from its masterful Flynn design. This year’s version of Shinnecock will have a new look and feel thanks to an exhaustive restoration (more on this in part 2). Gone are the trees and rye grass fairways, back are the firm, fast and open windswept corridors and fescue grasses.

The design

No single hole at Shinnecock is overwhelmingly hard, but no hole is easy. Great play is rewarded with scoring opportunities, while average play yields difficult pars. Shinnecock is a sum of all of its parts – the uneven lies, wind and vexing green complexes wear on players over 18 holes. Playing it is like stepping into the ring against Floyd Mayweather. The course doesn’t rely on singular holes to deliver knockout punches but rather lies in wait for tactical mistakes ready to punish them.

The high aerial showcases the rolling topography at Shinnecock Hills

Shinnecock’s architect William Flynn is one of the most underappreciated of the Golden Age. Flynn’s calling cards for design were exceptional routing, variety and challenging par-3s. Shinnecock Hills is Flynn’s best work, but he was also instrumental in the designs of Merion’s East Course and Pine Valley to go along with his solo designs of Kittansett, Cherry Hills and many others. Flynn has earned the nickname “The Nature Faker” for his ability to blend artificial elements into the natural landscapes of his courses. Shinnecock is his masterpiece, a course where no hole, shot or feature is out of its natural element.

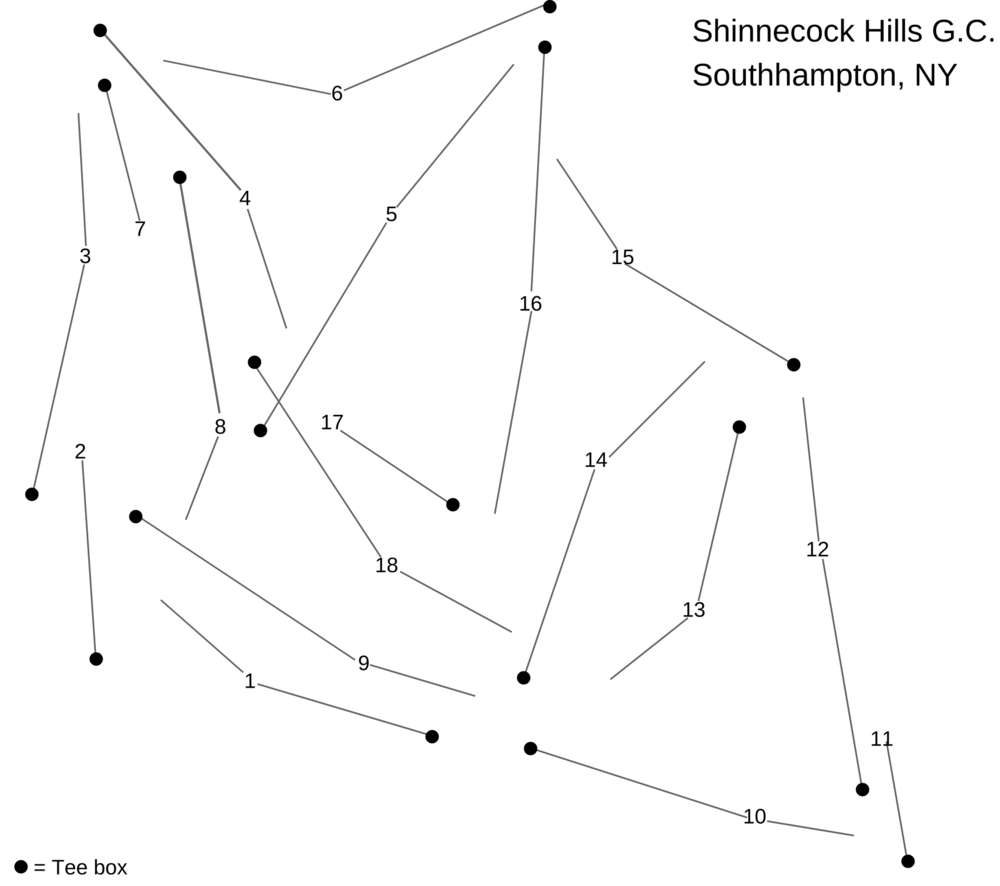

Shinnecock’s routing

To understand the brilliance of Shinnecock Hills, it’s essential to understand the routing. William Flynn spent more time on-site during the design process than most of his Golden Age contemporaries, and that shows in his routings. The course tumbles and weaves over a magnificent and stunning piece of rolling, sandy land. The routing provides exceptional variety from hole to hole. With the exception of the ninth and tenth, every hole plays in a distinctly different direction than its previous and asks a different question (short par-4, long par-4, par-3, par-5). It allows the wind to come from a different direction hole to hole and keeps players from getting comfortable. The ninth and tenth are the only two successive holes on the course that play in the same direction and close to the same distance. This is because the club decided to flip Flynn’s nines shortly after the course reopening. In Flynn’s plan, the ninth was the eighteenth hole, and the tenth was the first.

The routing can be broken down into three unique sections. The first eight holes play in the sandy lowlands of the golf course. They give players the flavor of Shinnecock, with each playing in a different direction. Players are wise to take advantage of the scoring opportunities presented on the first, fourth, fifth and eighth holes.

The second phase of the routing starts on the ninth hole, which scales the massive ridgeline that runs through the golf course into the highlands section. The second shot on the ninth hole feels like scaling a mountain. The highlands section is where the full effect of the elements and topography will be felt. It features the difficult par-4 ninth, tenth and twelfth, but also the short par-3 eleventh and par-4 thirteenth. On a windy day, hitting wedge shots into the tiny repelling greens of the eleventh and thirteenth are terrifying.

The fourteenth begins the close to Flynn’s masterpiece. The long par-4 hugs the low end of the ridgeline. The fifteenth plays from the top of the ridge down to the lowlands before the brawny par-5 sixteenth plays back up towards the ridge and clubhouse, offering players their last great chance at birdie. The challenging seventeenth and eighteenth finish out Flynn’s symphony with holes that test the nerves.

Shinnecock’s variety is unparalleled in the United States. It requires every club and shot in a professional’s arsenal. Shinnecock is a course that won’t favor a particular style of play. It has enough width to allow the shorter player to use accuracy while not taking the driver out of the long player’s hands. The green complexes’ rolled-over edges and short grass surrounds create a razor thin margin of error. The undulating fairways will produce a bevy of uneven lies that, coupled with ever-changing wind directions, will make it excruciating to control distances. A shot one yard from perfect can mercilessly tumble 30 yards away. The severe nature of the slopes of the greens will test a player’s touch and also command respect and thoughtful approach play. Shinnecock Hills will expose any and all flaws in a player’s game. It’s the finest major championship venue in the game because it asks the widest variety of questions to players. Shinnecock Hills will crown the week’s most well-rounded and skilled golfer.

In part two of our three-part Shinnecock Hills preview, we will dive into the restoration and what’s changed since the 2004 U.S. Open. Part three will go into the architecture behind some of Shinnecock’s key holes and what types of skills will be needed to succeed.

by

by