As often as I wish for it, time travel is still unavailable. So I’m left to daydream about what certain golf courses used to be.

The one I daydream about most is Yale Golf Course. Maybe the clearest testament to Yale’s original greatness is its current form. Despite decades of overgrowth and a few acts of architectural malpractice, it remains one of the country’s finest courses.

Yale is jarring to the senses. The scale of the land and the architectural features have to be seen to be believed. The course is full of blind shots and massive, undulating greens. It will test your definition of what is and isn’t fair, and for that reason it has always been polarizing among players. To put it differently, it will reveal what type of golfer you are: one who prefers golf that’s “all right there in front of you” or one who enjoys the adventure of the unknown. If you’re the latter, you will find at Yale an 18-hole thrill ride in which you will vie against not only the golf course but also nature.

Yale’s grand ambitions

Sarah Wey Tompkins, widow of the great 1880s Yale College athlete Ray Tompkins, donated the land that came to be known as the Ray Tompkins Memorial. On this 720-acre tract of forest, the first development was the golf course.

The decision to build the course was spurred by Yale’s slipping stature in the sport. After winning the 13 of the first 20 national championships, Yale Golf went seven years without winning one. By 1922, as other programs, including rivals Harvard and Princeton, already had or were building dedicated golf facilities, Yale saw that it was time to do the same. In this way, the genesis of Yale Golf Course is similar to that of the Philadelphia School of Architecture: failure in competition led to architectural action. The belief was that great courses produced great players.

Yale University’s Board of Trustees appointed a golf committee that consisted of some of the game’s biggest figures: George T. Adee, Chairman; Mortimer Buckner, former Treasurer of the USGA; J. F. Byers, President of the USGA; Robert A. Gardner, Vice President of the USGA and two-time U.S. Amateur champion; and Jess W. Sweetser, another U.S. Amateur champion. With the intention of building the country’s finest championship golf course, this group reached out to the country’s most prestigious golf architect, Charles Blair Macdonald.

Enter MacRaynor

For C. B. Macdonald, golf architecture was a hobby. He designed courses for himself and for his rich and famous friends. By 1923, when Yale reached out to him, Macdonald had “retired” from his hobby. Friends on the University’s board, however, persuaded him to visit the site with his protégé Seth Raynor. The land, while stunning, was rugged; five years later, in his book Scotland’s Gift: Golf, Macdonald called it a “veritable wilderness.”

The rocky ledges, severe topography, thick forest, and poor soils led to hefty construction budget. In fact, at nearly $450,000, Yale Golf Course’s construction budget was the biggest of the Golden Age of golf architecture—bigger even than Lido’s. With heavy use of saws, steam shovels, and dynamite, Macdonald and Raynor, along with associate Charles Banks, built a golf course in an unthinkable location.

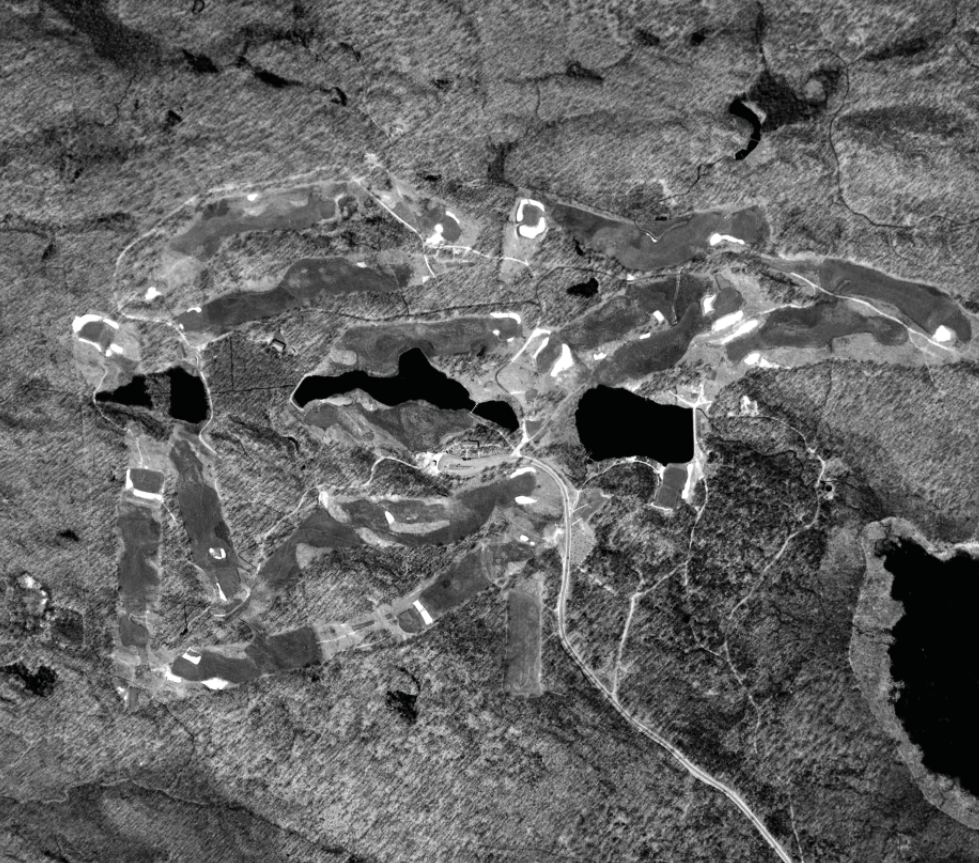

A 1934 aerial view of Yale Golf Course

Design brilliance

As soon as it opened, Yale thrust itself into the conversation about the greatest courses in the United States. Banks wrote about the course’s “rugged and massive features,” which he said would “stir the golfer’s soul.” He continued: “Here the architect has fashioned an Alps Hole, here a Cape, here a hint of the well known Road Hole. Not a single hole on the course is even fairly suggestive of any other one on the entire 18. Each hole has its own peculiar appeal—its own individuality. As a result, there is no monotony. The appeal to the eye is continuous and the appeal to the golfing sense is unfailing.”

The grandness of the natural terrain and the university’s championship ambitions gave Macdonald, Raynor, and Banks license to create uniquely wild renditions of their “ideal holes.” In this way, Yale stands in contrast to Chicago Golf Club (Macdonald and Raynor), Country Club of Charleston (Raynor), and Westhampton (Raynor), where adventurous greens drive interest on less dramatic land. Yale also differs from Shoreacres, Fishers Island, and Yeamans Hall; at those courses, which have striking natural features, Raynor built more subdued greens. At Yale, however, the design team went full-bore, matching bold, severe land with bold, severe greens.

The holes at the Yale course belong unmistakably to the Macdonald tradition, but many are remixes or dialed-up versions of the classic templates. Others are original designs that simply fit the terrain. This variety of hole designs is exemplified by the stretch from No. 8 to No. 10.

The par-4 8th combines a Cape concept with a one-of-a-kind double-Redan green. The front half of this green is a traditional, right-to-left Redan, and the back half is a left-to-right reverse Redan. Golfers will not see this combination at any other MacRaynor design. For many years, players hit blind long-iron approaches into this massive and severe green complex. Former Yale golfer and current Yale Men’s Golf coach Colin Sheehan recalls “hitting a blind 6-iron into a cross-wind and praying not to make a nine.” Today, however, advances in equipment technology have turned the hole into a birdie opportunity. Members of the current Yale Men’s Golf team can usually crest the hill with their drives and earn a clean look with a wedge.

-

The rolling terrain of the 8th hole at Yale

-

The front of the 8th green (midway through the process of expansion) at Yale

-

The massive exterior contours of the 8th green at Yale

-

Behind the 8th green at Yale

-

Another look at Yale's bold 8th green

It would be strange to discuss the severity of Yale’s design without mentioning the Biarritz 9th. This 235-yard par 3 has a massive 65-yard green with the deepest swale of any Biarritz built by Macdonald and/or Raynor. For additional challenge, the hole plays over a water hazard, making front pins arguably more exacting than back ones.

-

From the 9th tee at Yale

-

The boldly contoured Biarritz 9th at Yale

-

From the left side of the 9th green at Yale

-

Yale's Biarritz 9th

On the 10th, the architects moved away from their customary ideal holes. This brute of a par 4 plays over the property’s most severe terrain and embodies the adventure of the Yale course. The tee shot, blind and over a large hill, plays to a rolling fairway. A long drive will tumble down a ridge to a large hollow and leave an approach up what feels like a mountain. A shorter hit off the tee will result in a less uphill but much longer shot to a green fronted by two treacherously deep bunkers. At the green, Macdonald, Raynor, and Banks didn’t take their foot off the gas, building distinct front and back tiers separated by a severe slope. Like the 8th, the 10th has lost some of its teeth for better players today. The high-launching, low-spin ball makes the titanic uphill slope much more attainable.

-

Riley Johns about to tee off on the 10th at Yale

-

A look at the intimidating target from the 10th fairway at Yale

-

The 10th green at Yale from the right side of the low point in the fairway

-

The severe back-to-front slope of the 10th green at Yale

-

A look from above at the 10th green at Yale

-

The 10th (left) and 18th (right) at Yale

On the road to lux et veritas

Yale Golf Course’s deterioration over the years is a familiar story. Trees encroached, greens shrank, and deferred maintenance piled up. The course lost its double-punchbowl 3rd green and had to move its 16th green because of drainage issues. All of these changes added up to a course that rarely played the way that Macdonald and Raynor intended.

Furthermore, a “restoration” attempt from Yale alum and former Robert Trent Jones associate Roger Rulewich pushed Yale further from its original form. While Rulewich should be applauded for restoring the Alps design on No. 13, his bunker work was abominable. In many cases, he reduced the slope of the bunker faces, softening the trademark brashness of the course’s shaping. A case in point is the Eden hole, No. 15. Originally, the front “Strath” bunker had such a steep face that growing grass on it was impossible. To avoid maintenance problems while retaining the challenge and severity of the bunker, the architects installed wooden planks. Rulewich removed the planks and softened the slope. Today, more balls end up in the grass than in the bunker.

The Eden 15th at Yale, with its softened, angled bunker faces

Despite such miscues in its stewardship, the course remains enthralling. It has natural intangibles that neglect cannot take away. With its topography alone, Yale produces more interest than most courses have.

Plus, the Yale course is well on the road to recovery. In the past decade, its conditioning and presentation have improved by leaps and bounds. Golf course superintendent Scott Ramsay has tackled many of the issues that plagued the course, clearing trees to reopen lost corridors, expanding greens to regain lost pins, and improving drainage to allow the course to be playable after rainfall. Ramsay’s work has led to a revival in the popularity of the course and hope for more improvement. It’s a tribute to the importance of an informed and energetic superintendent.

Today, Yale remains a course that will inspire you and deepen your love for the game. By all rights, it should belong to the top echelon of American golf courses, alongside National Golf Links of America, Cypress Point, and Shinnecock Hills. But until it undergoes a faithful restoration, Yale will remain golf architecture’s greatest what-if.

For golf fans who want to bring home a piece of this course, we offer a collection of Yale photography prints shot by the Fried Egg Golf team available in our Pro Shop.

Sign Up for The Fried Egg Newsletter

The Fried Egg Newsletter is the best way to stay up to date on all things golf. Delivered every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday for free!

by

by