Caddies are a strange breed. Specifically, the club caddies: the everyday-ers, hustlers, bag bandits who pull two loops a day around the same course at $70 per shoulder. The pursuit of cash—however you can earn it—is the purest drug for a caddie. It’s just about the only thing that unites the array of characters who lug bags.

A swab-check at a golf club’s caddie shack reveals—amid the mold-ridden stains, stagnant clouds of tobacco, and bodily fluids—a petri dish of personas and realities: the country club kids (children of those fortunate enough to manage the $35,000-plus annual membership fees), the wannabe pros (detail-obsessed perfectionist cutthroats who have every intention of making it on Tour), and the Davy Jones crew (background-check evaders, outlaws tethered to the shack like pirates to a vessel).

Not every caddie fits one of these types. I didn’t. At the age of 15, I grabbed the bib and towel to prepare myself for student loans and inevitable debt. Each morning I joined the lineup for our 5:45 a.m. “Brae Burn Breakfast”: iced black coffee, cigarette, loop. Same for lunch.

Yet behind the shabbiness of a caddie shack lies an opportunity. It may not feel that way to the club kids, the wannabes, the pirates, and the misfits like me as they swarm on scraps of money, living and dying by member-guest weekends. But there’s a bigger picture here. The health of caddie programs in general is terribly important to golf.

Caddying introduces a broad and diverse swath of young people to the game. While golf itself can be expensive and inaccessible, you don’t have to be rich to carry bags. Plus, most courses with caddie programs allow loopers to play for free on certain days of the week. This provides an entree into golf for those who might not otherwise have had the opportunity. Yes, the caddie vs. member dynamic can—and, in some instances, should—drive resentment. But if you worry about the future of golf, consider how much caddie programs do to introduce young people to the game.

The professional circuits were once full of players who grew up with little socioeconomic privilege but gained access to golf through caddying: Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Sam Snead, and Lee Trevino, to name a few. Carrying bags was an equalizer for these players, allowing them to spend as much time on the course as wealthier kids. But the post-WWII golf real estate boom, along with the advent of the motorized cart, cheapened the value of caddies. The path taken by Hogan, Nelson, Snead, and Trevino all but closed. As caddying has declined, so has the frequency of the rags-to-riches story in pro golf.

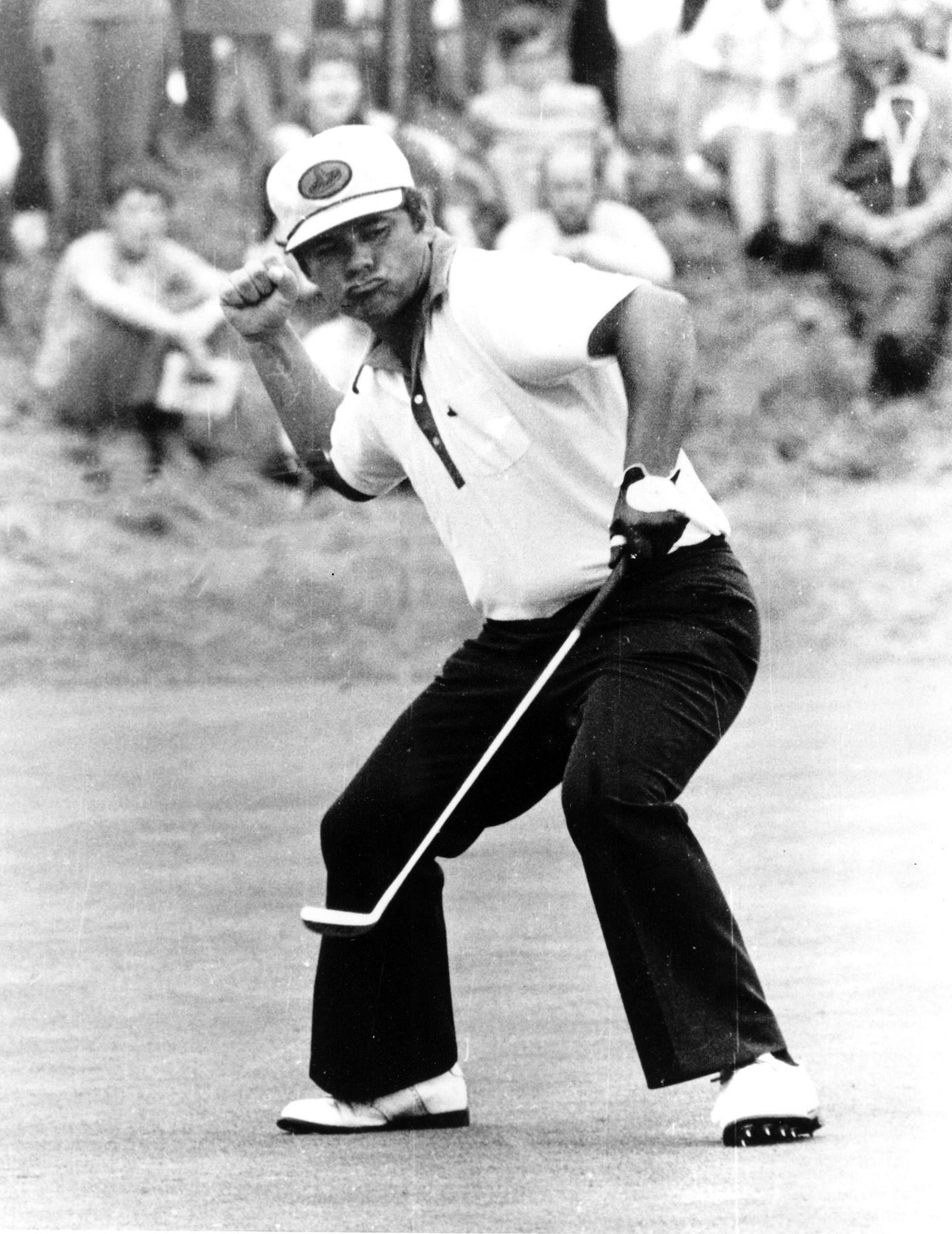

Lee Trevino, one of the many great golfers of the past who caddied as a youngster

It’s simple: we need more caddie programs. Public golf courses in particular have room to improve in this regard. By one recent count, there are only about 150 public courses in the United States that maintain active caddie shacks, and many of these are in just a handful of states. Maybe public golf facilities figure that their customers wouldn’t use caddies. The truth is, though, that a thriving caddie program offers profound benefits, many of which might not be immediately apparent.

First, think about the caddies themselves. Loopers learn all kinds of important lessons. Mastering the hand-rolled cigarette with two bags on your shoulder. Finessing the optimal body contortion to take a piss while trudging through the woods. Looking for some hack’s errant tee shot while remaining undetected by the group of 70-something ladies on the neighboring hole. But there are also softer, more résumé-friendly lessons: self confidence, humility, money management, decisiveness, how to admit when you’ve messed up, an ability to identify bullshit, an ability to deliver bullshit, doggedness, how to talk someone off the ledge. The list goes on.

Second, a strong caddie program gives back to the course itself. Caddies are field-marketing experts—perhaps the most honest and effective ones a course has. They are seldom paid employees, so they have little vested interest in sugar-coating course conditions or feeding the company line on why someone should “really consider pulling the trigger on the annual membership.” But good caddies know that in order to get that extra ten bucks, they better bring their A-game. They better be well-versed in green reading and golf course architecture, and they better have a sharp wit as well as an understanding of when to remain absolutely, godforsakenly silent. These skills are as much assets to the course as they are to the caddie. They ensure the quality of the golf experience.

A player and a caddie on the 14th hole at Old Macdonald. At Bandon Dunes Golf Resort, caddies are integral to the experience. Photo credit: Rich Morrison

Third, a 16-year-old caddie will often grow up into a 36-year-old, green-fee-paying golfer.

While caddying has declined in the past several decades, it’s not completely out to pasture. Companies like CaddieNow and Baggr Caddies have fostered a shared economy around pairing golfers with available caddies. College scholarship foundations like Evans in Illinois and Ouimet in Massachusetts incentivize high schoolers to get under the straps. Still, we have a long way to go.

I would never have caught the golf bug if it weren’t for my time in the caddie shack. Seeing countless putts sunk or lipped for high stakes, learning to appreciate the raw beauty of a Donald Ross design, and being surrounded by every type of character imaginable made me hungry for more. Build a caddie shack, build the game.

Connor Laubenstein is a former looper who manages The Bag Bandit, a collection of writing on caddies and golf style. Find Connor on Twitter @bag_bandit and on Instagram (thebagbandit).

The Fried Egg’s Sunday Brunch series presents golf stories that don’t fit the usual categories. Learn more about the series here.

by

by