As the Texas summer sun beat down on the second round of the 1971 Colonial National Invitational, Dave Hill decided he’d had enough. He was 16 over par that Friday, walking toward a drive he had just topped. To make things easy on his caddy, Hill decided to play the last few holes with just his 9-iron. His approach into the 18th green—a smooth 9—left him with a brutal lie in a green-side bunker. Upon seeing the lie, Hill picked up the ball with his hand, rolled it onto the green, tapped in with his 9-iron, and promptly disqualified himself for taking an illegal drop.

◊

Dave Hill grew up 40 miles west of Ann Arbor, near the small town of Jackson, Michigan. His father worked jobs at both the post office and the local factory, and he freelanced as an accountant. Hill’s mother was tasked with raising the six children. As if that wasn’t enough, the family owned a 60-acre farm, where they raised cattle, pigs, and riding horses. The kids tended the vegetable patch and did odd jobs like bailing hay.

By all accounts, Dave Hill was a pretty average boy. He was bullied frequently. “The other kids picked on me because I stuttered badly in school until the eighth grade, from nervousness,” he says in his 1977 book Teed Off. “The stuttering made me a terrible loner, which caused the bullies to pick on me all the more. I hate to think of the beatings I’d have taken if Mike and his strong left hook hadn’t been alongside me.”

Mike was Dave’s younger brother, but he took on the older brother’s protective role. “Growing up, Mike was my only friend,” Dave wrote. “He could whip everybody in the tough end of town… and I learned early that I wanted him on my side.” Which isn’t to say that Dave never got in fights; he just didn’t win many of them.

The Hills’ land was adjacent to Jackson Country Club. Dave’s parents allowed him to start caddying at the age of nine, under the tutelage of older brother George. The club pro cut down some clubs for Dave, and he played on Monday mornings during caddie day. His swing was completely self-taught. “I learned the basics of swinging a golf club mostly by imitation,” he wrote. “I caddied for some of the good players around Jackson and picked up a lot just observing them and then trying to mimic them.”

Dave also played basketball and football, but his small frame held him back. Still, his drive and attitude made him a pest, especially in basketball. “I was a little pecker, and I figured I had to play aggressively or I would be run off the court,” he said. “I fouled out of three out of every five games.” Hill brought the same competitive spirit to the golf course. “When I get mad on the golf course, which is frequently, I feel mean.”

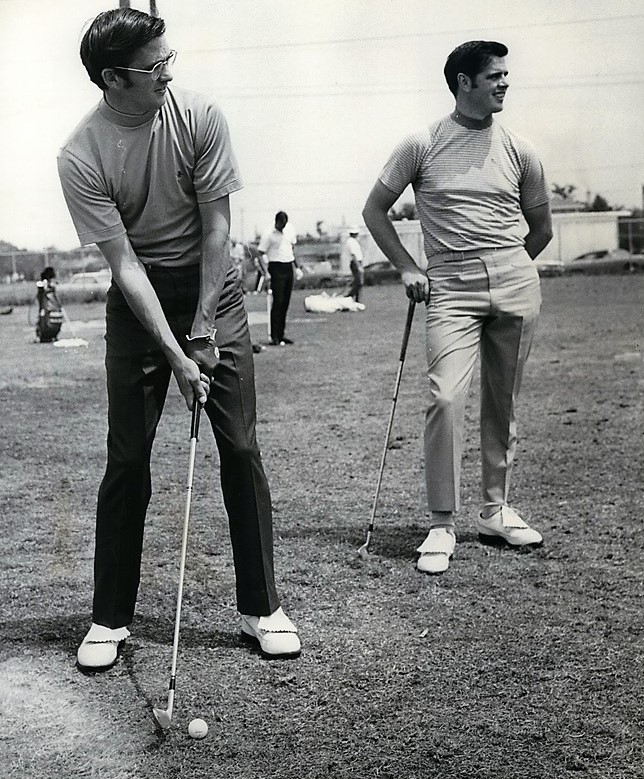

Dave Hill (addressing the ball) with his brother Mike

◊

Hill turned professional in 1958 at 21 years old, and he went on to rack up 13 victories, play on three Ryder Cup teams, and win the 1969 Vardon Trophy for the lowest scoring average on tour.

But while he established himself as a consistent competitor in the ’60s and ’70s, it was his personality and sound bites that made him truly noteworthy. “If you ask me a question,” he wrote in his book, “I am going to answer it. If the answer offends you, that’s not my problem. If you bug me, I’ll insult you and forget about it. Many people resent my attitude. Many are jealous; they’d like to say what they think but are afraid to.”

As we’ve seen over the years, strong personalities tend to rub the PGA Tour brass and other players the wrong way. Those run-ins started early for Dave Hill.

In 1961, the year Hill captured his first win at the Tucson Open, he was routinely dinged by the Tour. “I paid something like $1,400 in fines, most of them for breaking putters. It cost me $100 per broken club,” he wrote. That $1,400 amounted to half of his first-place check for his win in Tucson.

Hill’s first major dust-up with the Tour came in 1963. His father died early that season, so he wasn’t in a good state of mind. At the Frank Sinatra Open Invitational in November, Hill was in the midst of one of the worst putting stretches of his career. On the 18th green, he approached Tour director Joe Black and told him that if he missed his birdie putt he would break his putter. “He said, ‘Oh, you don’t want to do that.’ And I said, ‘I just promised myself I would.” After missing the putt, Hill snapped the putter over his knee and finished out with half a putter. The Tour committee suspended him for two months.

Three years later, Hill missed the cut at the ’66 Thunderbird Classic by 108 shots. That’s not a typo. 108 shots. Okay, so he didn’t actually hit the ball that many times. Rather, he shot rounds of 79-78, and after making a mess on the 18th hole on Friday, Hill’s playing partner Gardner Dickinson asked what he made on the hole. “Eight or 108,” Hill replied. Dickinson recorded the eight, but Hill added “10” in front and signed for a second-round 178. He was originally DQ’d for signing an incorrect scorecard, but since he signed for higher than the correct score, his total was recorded as 257 for the two days.

We’re just getting started.

◊

June of 1970 was a busy month for Dave Hill. It started with a run-in with Chi-Chi Rodríguez at the Kemper Open. On Sunday, the two played 36 holes because of a weather delay earlier in the week, and Hill was in contention. But if you know anything about Chi-Chi Rodríguez, you know he caters to his fans. His antics angered Hill, who believed that the distraction cost him a chance to win. The pair nearly came to blows on the back nine. After the round, in the locker room, they did come to blows. “I’m sure I could have killed him, the frame of mind I was in,” Hill wrote. “Officials kept me away from him and got him out of there.”

Two weeks later, Hill finished second in the U.S. Open at Hazeltine, his career-best result in a major. But as you can probably guess, that wasn’t the story of the week in Minnesota. “I’m sure I could have been more discreet in my remarks to the press,” Hill wrote seven years afterwards. “I never said anything at Hazeltine that wasn’t an answer to a newsman’s question, and for that I was crucified.”

You see, despite his high finish, Dave Hill didn’t particularly care for Hazeltine National Golf Club. After a second-round 69 got him in the mix, the press requested comments from Hill. He turned them down and hit the bar. “I chugged down four or five vodka and tonics on an empty stomach and was feeling no pain when they asked me again, and I went,” he recalled.

The first question was about the venue. Back then, Hazeltine was just eight years old. Former USGA president Totton Heffelfinger (yes, that is an actual name) had become the president at Hazeltine and used his influence to secure the 1966 U.S. Women’s Open and the 1970 U.S. Open. A brand-new Robert Trent Jones design in rural Minnesota, Hazeltine was an easy target.

So what did Hill think about the course? “I’m still looking for it,” he said. According to his book, he proceeded to add some color: “I said I thought Mr. Jones ruined a beautiful piece of farmland. I’m a farm boy and I know a good piece of farmland when I see one. Mr. Jones had ruined what could have been a fine farm.”

Hill’s comments were clearly tongue-in-cheek, but his tone got lost in translation when the papers came out the next day. Most of the players actually agreed with Hill’s comments. “What he said about Hazeltine was the absolute, honest-to-God truth,” his brother Mike Hill said. “Players like Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player sat in the locker room and laughed. They knew it was true, but because of them not wanting to be involved, they would never say it.”

For the rest of the week, the galleries heckled him good-naturedly, and Hill gave it right back. He even went across the street and cooked up a scheme with a local landowner. “I paid the farmer $50 to let us use his tractor if I won,” he said. “I was going to drive out on the course on it holding up the trophy for kicks.” Unfortunately for us, Tony Jacklin won the event by seven shots over runner-up Hill, and what would have been one of the greatest celebrations in golf history never happened.

◊

That brings us to 1971 and the “hand-mashie” incident at Colonial Country Club.

Hill’s frustration began long before he arrived in Fort Worth. Earlier that year, he was playing at Palm Springs, and his ball landed in a palm tree. It was close enough for him to see it and identify it as his ball. Gallery members confirmed the ID. Still, since Hill had not put his personal marking on the ball, the rules committee disqualified him. There wasn’t even a specific rule that required such a marking. Hill was irate, and his anger simmered all season before boiling over at Colonial.

“I didn’t throw [the ball],” he explained. “I had a nice touch on it actually—it finished about two feet from the hole.” The record shows that Hill was disqualified for signing an incorrect scorecard, but he claimed he DQ’d himself.

The next week, Hill traveled to the Memphis Open Invitational, an event he had won twice in the previous four years. There he received a phone call from the Tour saying he was being fined $500 and that he would have to pay up before competing again. He wasn’t allowed to give his side of the story, which he felt was a violation of player procedures. So he paid the $500, entered the event, and filed a $1-million antitrust lawsuit against the Tournament Players Division (which was what the PGA Tour was called back then). The TPD board put Hill on a one-year probation, and he responded by upping the demand to $3 million.

The lawsuit dragged on for months, and eventually the two sides settled out of court. “I really think I could have won the suit,” he wrote. “But I didn’t want it on my mind any more. I’m a golfer, not a political rabble-rouser. I figured I got concessions on eleven points from the TPD and those were worth what they cost me.” Those concessions centered on what Hill described as the TPD’s selectiveness with fines. “I firmly believe there is prejudice in applying the rules and regulations of the Tour and fining people. The rules aren’t the same for Dave Hill or Ray Floyd as they are for Jack Nicklaus or Arnold Palmer. If you’re a big name, you’re protected when you have a little temper tantrum.”

After the settlement, the TPD created a system that defined the consequences for different infractions. Hill’s probation was removed, and he won six more times in the ’70s.

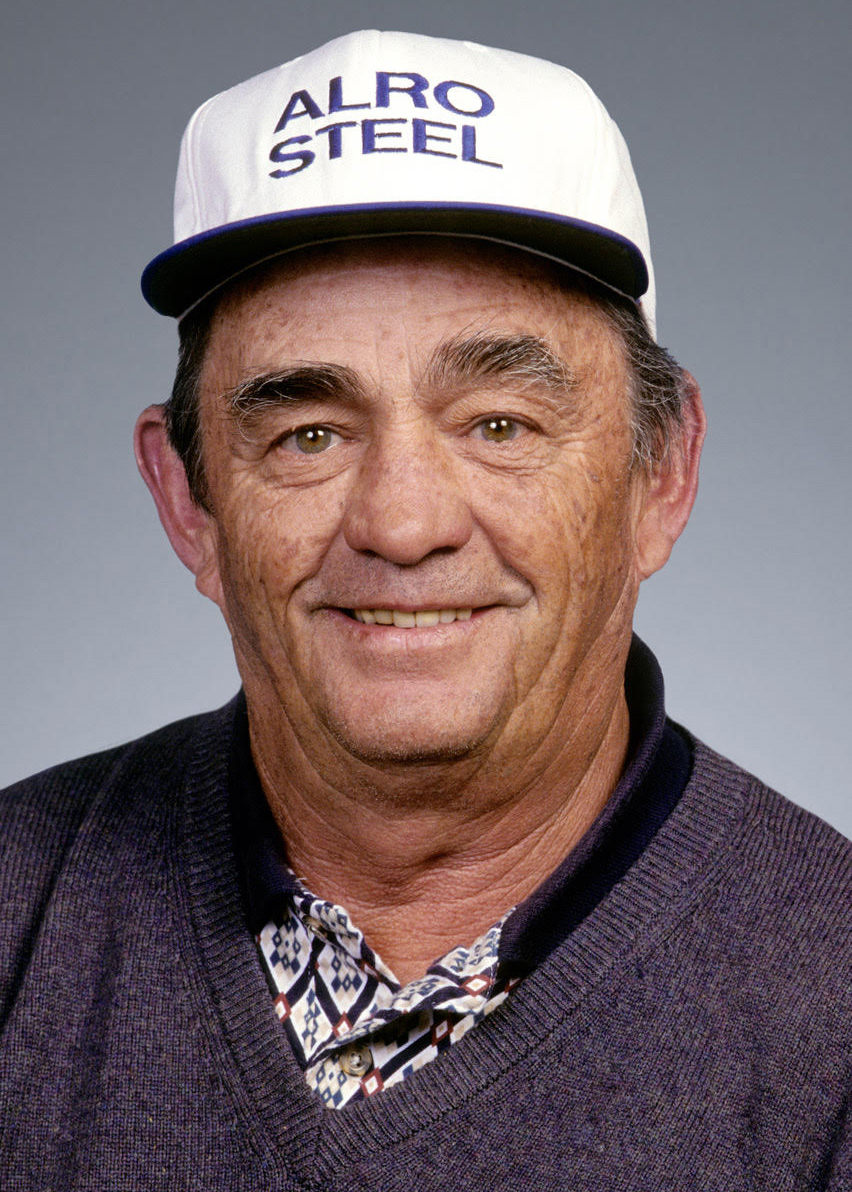

Dave Hill in his later years

◊

Dave Hill passed away in September of 2011. He was one of the best ball-strikers of his generation and a legend in the press room. His brother Mike served in the Air Force in the 1960s and went on to win three PGA Tour events and 18 Champions Tour events.

We could use more golfers like Dave Hill. It’s refreshing to read about a Tour player who wasn’t afraid to speak his mind. Was he perfect? Absolutely not. He was a red-ass and a curmudgeon. Even in writing, he has a tendency toward the politically incorrect. But he was unapologetically himself. He had the gall of Brooks Koepka, the scrappiness of Billy Horschel, and occasionally even the thoughtfulness of Rory McIlroy. He wanted to have fun on the golf course and maintain his sense of self—things we could all manage to do as well as he did.

“It’s amazing how much easier the game can be when you’re able to relax,” Hill wrote. “I can hit better golf shots playing for funsies than I can playing in a tournament, because I’m not afraid of anything. I enjoy that.”

This article is part of The Fried Egg’s Sunday Brunch series, which focuses on golf stories that don’t fit the usual categories. Find out more about the series here.

by

by