Many of the great Golden Age architects have legacies that can be summed up in a sentence. C.B. Macdonald was the grandfather of golf in the United States; Donald Ross was the remarkably prolific, designing over 400 courses; A.W. Tillinghast was a master at building stern championship tests. So what about Alister MacKenzie?

Many would argue that he was simply the best of his time. MacKenzie’s brilliance spans the globe: he designed arguably the greatest courses in North America (Cypress Point and Augusta National), Australia (the West Course at Royal Melbourne) and South America (the Jockey Club) as well as some great courses in Great Britain and Ireland. He was renowned for his ability to blend design features seamlessly into the natural beauty of his sites. His courses provide strong and interesting tests for scratch players while remaining fun and playable for average golfers.

Let’s dive a little deeper into how Alister MacKenzie found his way into golf course architecture and how he shaped the industry for years to come.

Background

Dr. Alister MacKenzie grew up near Leeds, England. He went to Cambridge University to become a doctor and served in Great Britain’s military during the Boer War and later in World War I. During the Boer War, MacKenzie became fascinated with the Boers’ use of camouflage, a skill he eventually mastered himself. Later, his knowledge of camouflage would prove relevant to his golf course architecture practice.

After his university years, MacKenzie caught the golf bug and played at Leeds Golf Club before becoming a founding member of Alwoodley Golf Club. It was at Alwoodley that he would get his first taste of golf course design: he served on the green committee and ultimately laid out the course himself.

MacKenzie’s design at Alwoodley was bold and ahead of its time—so much so that his green committee colleagues called in the already established architect Harry Colt to give advice. Much to the chagrin of the committee, Colt approved of MacKenzie’s ideas and was impressed with his understanding of how the modern golf ball was changing the game.

-

MacKenzie's first design at Alwoodley Golf Club. Photo: Simon Haines

-

MacKenzie's first design at Alwoodley Golf Club. Photo: Simon Haines

-

MacKenzie's first design at Alwoodley Golf Club. Photo: Simon Haines

Shortly after Alwoodley’s completion, MacKenzie got the opportunity to design another course, this time just down the road at Moortown Golf Club. The membership had raised only $500, which wasn’t enough for 18 quality holes, so MacKenzie advised them simply to build one great hole. The resulted was the famed “Gibraltar Hole.” The greatness of what is now the 10th hole at Moortown attracted more members and money. MacKenzie proceeded to design the rest of the course, which ended up hosting the Ryder Cup in 1929.

MacKenzie's famous Gibraltar Hole at Moortown Golf Club. Photo: Simon Haines

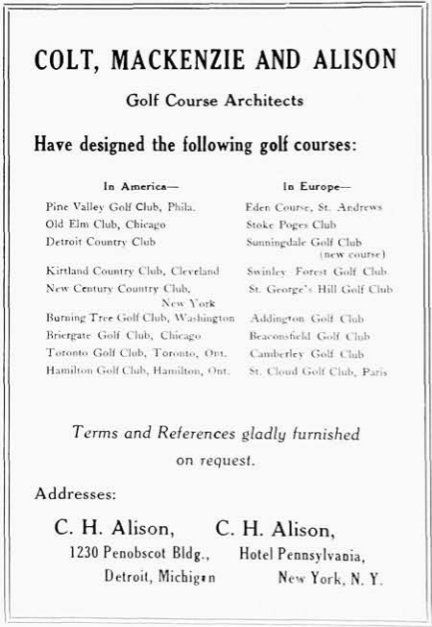

Just when MacKenzie’s design career was taking off, World War I began. After his service in the war, he decided to give up medicine and pursue golf course architecture full-time, joining forces with Harry Colt and Charles Alison.

Research credit: Simon Haines

After four years with Colt and Alison, MacKenzie struck out on his own and embarked on a flurry of trips trips to Ireland, Australia, the U.S., and South America. He became one of the first truly international golf course architects, boasting multiple designs on four different continents.

During his stint in the U.S., MacKenzie formed partnerships with two talented American architects, Robert Hunter and Perry Maxwell. Hunter assisted on West Course courses such as the Meadow Club, Cypress Point, and Pasatiempo. Maxwell teamed up with MacKenzie on several designs in the Midwest, including Crystal Downs and the University of Michigan Golf Course.

MacKenzie’s last great design was a collaboration with legendary amateur Bobby Jones in Augusta, Georgia. You know the one. But just two and a half months before the inaugural edition of the Augusta National Invitation Tournament—which later became known as the Masters—Alister MacKenzie died suddenly of a heart attack. He was 63 years old.

-

The 13th hole at Cypress Point

-

The 16th green at Pasatiempo

-

The seventh hole at Crystal Downs

-

The fifth hole at Royal Melbourne West. Photo: Michael Clayton

-

The fourth hole at the somewhat run-down but enchanting Northwood

Design principles

Unlike many of his contemporaries in golf course architecture, MacKenzie was not an elite player. This likely served him well, giving him real insight into how to create interest and playability for the average golfer. His most important inspiration was the Old Course at St. Andrews, which he considered the gold standard of golf course design. What stood out most to him about St. Andrews was its naturalness, strategic complexity, and capacity to “give the greatest pleasure to the greatest number.”

So what are MacKenzie’s design principles? Thankfully, he set them down himself in a handful of digestible bullet points. MacKenzie’s “13 principles” are famous and have been published in numerous places, including his books Golf Architecture and The Spirit of St. Andrews.

- The course, where possible, should be arranged in two loops of nine holes.

- There should be a large proportion of good two-shot holes, and at least four one-shot holes.

- There should be little walking between the greens and tees, and the course should be arranged so that in the first instance there is always a slight walk forwards from the green to the next tee; then the holes are sufficiently elastic to be lengthened in the future if necessary.

- The greens and fairways should be sufficiently undulating, but there should be no hill climbing.

- Every hole should be different in character.

- There should be a minimum of blindness for the approach shots.

- The course should have beautiful surroundings, and all the artificial features should have so natural an appearance that a stranger is unable to distinguish them from nature itself.

- There should be a sufficient number of heroic carries from the tee, but the course should be arranged so that the weaker player with the loss of a stroke, or portion of a stroke, shall always have an alternate route open to him.

- There should be infinite variety in the strokes required to play the various holes—that is, interesting brassie shots, iron shots, pitch and run up shots.

- There should be a complete absence of the annoyance and irritation caused by the necessity of searching for lost balls.

- The course should be so interesting that even the scratch man is constantly stimulated to improve his game in attempting shots he has hitherto been unable to play.

- The course should so be arranged that the long handicap player or even the absolute beginner should be able to enjoy his round in spite of the fact that he is piling up a big score. In other words, the beginner should not be continually harassed by losing strokes from playing out of sand bunkers. The layout should be so arranged that he loses strokes because he is making wide detours to avoid hazards.

- The course should be equally good during winter and summer, the texture of the greens and fairways should be perfect and the approaches should have the same consistency as the greens.

These principles informed all of MacKenzie’s best work and remain excellent guidelines for building a course. Observations of his designs reveal a few themes that are especially important: naturalness, the contouring of greens and fairways, and his thoughtful approach to bunkering.

Naturalness

During his military service, MacKenzie noted that effective camouflage on the battlefield entailed blending manmade features with natural landforms. He applied this technique to golf course design, becoming an expert at giving artificial earthworks the look and feel of natural terrain. When you play a MacKenzie course, it’s difficult to discern which contours were originally there and which were built.

Undulations

To MacKenzie, there wasn’t anything more boring in golf than flat fairways and greens, so he liked challenge players with sloping fairways and heavily contoured greens. Regarding his green designs in particular, MacKenzie had a tremendous knack for dreaming up unique, strategically compelling putting surfaces, but his collaborators—from Robert Hunter in California to Perry Maxwell in the Midwest and Alex Russell in Australia—deserve credit for executing the details.

Bunkers

MacKenzie often said that most golf courses had too many bunkers. To those familiar with his courses, this statement may seem slightly ironic, given that many of the good doctor’s courses are full of flashy bunkers. But every bunker on a MacKenzie has a well-thought-out purpose, whether strategic or visual. Some bunkers he placed precisely where players might want to hit their shots to attack a hole, others he built to distract and deceive.

The style MacKenzie used in constructing bunkers was equally distinctive. He learned from how soldiers dug trenches with gradual, curved slopes, which held up better than steep sides coupled with flat bottoms. This is why MacKenzie’s bunkers often have splashed-up faces and curved interiors that funnel balls to the middle.

The bunkering at Titirangi Golf Club, MacKenzie's only design in New Zealand. Photo: Chris Day

A little-known fact

Up until the time of his death in 1934, MacKenzie argued passionately for limiting the distance of the golf ball and instituting a six-club limit. He felt that new equipment technology was a threat to the architectural integrity of the world’s best courses. Sound familiar?

Notable private designs in the U.S.

Cypress Point Club (CA), Augusta National Golf Club (GA), Crystal Downs Country Club (MI), Valley Club of Montecito (CA), Meadow Club (CA)

Designs that you can play in the U.S.

Pasatiempo Golf Club (CA), University of Michigan Golf Course (MI), Scarlet Course at Ohio State University Golf Club (OH; must be accompanied by a student or alum), Northwood Golf Club (CA), Sharp Park Golf Course (CA; only a few original holes remain), Haggin Oaks Golf Course (CA; much of the original design is lost)

Notable international designs

West Course at Royal Melbourne Golf Club (Australia), New South Wales Golf Club (Australia), Titirangi Golf Club (New Zealand), Jockey Club (Argentina), Old Course at Lahinch Golf Club (Ireland; renovation), Cork Golf Club (Ireland), Alwoodley Golf Club (England), Moortown Golf Club (England)

Additional MacKenzie resources

- The Spirit of St. Andrews by Alister MacKenzie

- Golf Architecture by Alister MacKenzie

- The Life and Work of Dr. Alister MacKenzie by Tom Doak

- The Alister MacKenzie Society

by

by