For the average American golfer, it’s difficult to see much of the work of the great Golden Age architects. In the U.S., exclusive private clubs own many of the classics of MacKenzie, Tillinghast, Raynor, and others. This makes it tough for most golf course design enthusiasts to develop a firm grasp of any given architect’s style.

There is one big exception, however: the work of William Langford and Theodore Moreau, much of which remains accessible to the public at affordable courses in the Midwest. Langford & Moreau’s bold style is unmistakable and driven by their mastery of the steam shovel. With this earthmoving tool, L&M crafted massive bunkers and green complexes that infused strategy and a distinctive flair into their designs. While most associate the Golden Age with minimalism and “nature fakery,” L&M were maximalists, unafraid of manufacturing features that did not look totally natural. At the same time, they remained sympathetic to the land and let the native terrain to shine through.

-

The bold par-3 15th at Kankakee Elks

-

The short par-4 15th at Harrison Hills

-

The 8th tee shot at Iron River

-

The back nine at Lawsonia Links

-

The 3rd and 11th greens at Skokie Country Club

-

The 3rd and 2nd greens at Culver Academies

-

The 4th green on the original Langford & Moreau routing at Marquette Golf Club

After World War II, the bulldozer permitted earthworks on a much larger scale and led to an era of maximalists who could, and often did, shape every inch of their courses. In contrast, Langford & Moreau’s steam shovel allowed for plenty of creativity while still enforcing some constraints. They created interest where they needed it most and left everything else alone. In this sense, L&M’s Golden Age “maximalism” is roughly the equivalent of what present-day architects think of as “minimalism.”

A brief background

Like many Golden Age architects, William Langford was a stellar golfer. He starred on the Yale golf team while earning a degree in civil engineering. In 1918, he joined forces with Moreau, and they went on to design over 200 courses. Working out of Chicago, they stayed mostly in the Midwest, where they had to grapple with heavier soils and less interesting topography than their coastal contemporaries did.

Tasked with bringing the game to many small Midwestern towns, Langford & Moreau had an impact on local, everyday golf that went largely unnoticed. As a result, they have been vastly underappreciated over the years, and unfortunately much of their work has been poorly preserved or outright erased. Just a handful of remaining courses give a true sense of their brilliance. Thankfully, however, many of these courses are public, so if you want to learn about L&M, all you need is a sense of adventure.

Boldness

As Langford & Moreau were based in Chicago, they may have been influenced by C. B. Macdonald and Seth Raynor, the architects of Chicago Golf Club and Shoreacres. Also, during Langford’s stint on the Yale golf team, he likely spent considerable time at Macdonald’s National Golf Links of America.

Although Langford & Moreau undoubtedly absorbed influences from Macdonald and Raynor, their work was highly original. They embraced boldness of scale like no one else in the Golden Age, building some of the largest features of the period. Using the steam shovel, they blended enormous bunkers and green complexes into the natural slopes of their sites.

The first thing you notice about an L&M design is the large-scale, intimidating greens, which take the built-up pads of Raynor and Macdonald to new heights. Deep bunkers around these greens exact a penalty for misses and lead to challenging up-and-downs. A quintessential L&M creation in this vein can be found on the 15th hole at Harrison Hills. On this short par 4, the 30-foot bunkers on either side of the elevated green intimidate players and make wedge shots from anywhere seem fraught with danger. It’s a hole you have to see to believe.

On occasion, Langford & Moreau’s greens have been criticized. By building up their green pads, they limited the amount of variety they could create. It is rare, for instance, to see a fall-away green on an L&M course. That said, the pair had a knack for distinguishing their greens through intricate internal contours.

Because of the impressive external shaping of L&M’s greens, these subtle contours sometimes go unnoticed. Consider the 18th at Lawsonia, where the immense green is flanked by deep, punishing bunkers. But the most compelling feature of the green is the central spine, which differentiates precise from slightly imprecise approaches. If you find yourself on the wrong side of this ridge, you will do well to two-putt.

The 18th green at Lawsonia Links

L&M used the steam shovel to make players think before they get to the green as well. Their fairway bunkers often cut into their wide fairways, protecting different angles of approach and generating strategic questions. While L&M made these hazards large and taxing, Langford believed in always including a route around the hazards for the less skilled or daring player. Writing on golf architecture for the Chicago District in 1915, he asserted, “Hazards should be placed so that any player can avoid them if he gauges his ability correctly, so that they will make every man’s game more interesting, no matter what class player he is, and offer a reward commensurate with the player’s ability.”

For example, off the tee of the par-4 6th at Culver Academies, the aggressive line is straight over a fairway bunker. When it was built, this bunker could be carried only with a well-struck drive. The reward is an open and unprotected approach. The safe line to the left, on the other hand, yields an obstructed view and a forced carry on the second shot. So you can easily play around the bunkers on the 6th at Culver, but to score effectively, you have to take a risk on either the drive or the approach.

The strategy of the 6th at Culver Academies (bottom) is driven by bunkering

Naturalism

While Langford & Moreau applied the steam shovel aggressively, they excelled at routing their courses to take advantage of natural features. Unafraid of blind tee shots, L&M liked to drape fairways over rolling terrain, allowing slope to serve as an additional strategic hazard. On the 16th at Harrison Hills, for instance, the tee shot plays over a ridge to a fairway that tumbles to the right. Players able to hug the left side of the fairway get a clean look at the green. Less accurate shots, however, gather to the right side of the fairway, which offers an inferior angle and an obscured sightline.

Lawsonia Links, the finest remaining Langford & Moreau design, shows their routing prowess. The most compelling feature on the property is a large dip that runs through the rectangular paddock of the back nine. Along the two ridges on either side of this gully, L&M situated three greens and two tees, taking full advantage of its exciting slopes.

No. 13, one of the best three-shot holes in America, uses these slopes to perfection. Right where you might want to lay up on your second shot, the dip—some 40 feet deep at this point—crosses the line of play. Now you have to decide: lay up short of the swale and deal with a long third; hit into it, leaving yourself a blind shot from an uneven lie; or attempt to carry it, which could result in a short-sided wedge to a prototypical pushed-up and fiercely guarded L&M green.

In a later era, when blind shots came to be seen as “unfair,” architects likely would have softened the terrain on Lawsonia’s back nine. Fortunately, though, this wasn’t an option for Langford & Moreau in 1929. The constraints of their time forced them to come up with a creative solution for navigating the gully—a solution that ended up generating far more engaging golf than the bulldozer could have.

Furthermore, retaining the massive scale of the natural topography allowed their massive shaping at the green to fit in. Although tremendously large and clearly manufactured, the 13th green does not feel out of place because the large landforms around it are intact.

Balance in routing

Many of Langford & Moreau’s designs contain five par 3s and five par 5s, which allows for more than the usual amount of variety in a round. In particular, the pair’s ability to build memorable and varied one-shot holes stands out. Like Macdonald and Raynor, L&M used par 3s to examine all facets of a player’s game. For example, Spring Valley Country Club in Salem, Wisconsin, has five par 3s of 138, 231, 181, 170, and 190 yards. Each plays in a different direction and requires different types of lofted and running shots.

-

The short par-3 3rd at Spring Valley

-

The long par-3 5th at Spring Valley

-

The medium-length 7th at Spring Valley

-

The stellar 11th at Spring Valley

-

The medium-long 17th at Spring Valley

Nine-hole designs

As they tended to work in remote areas where money was tight, Langford & Moreau built a lot of nine-hole courses. Often they would take a wait-and-see approach with clients, giving them 18-hole designs but building only nine.

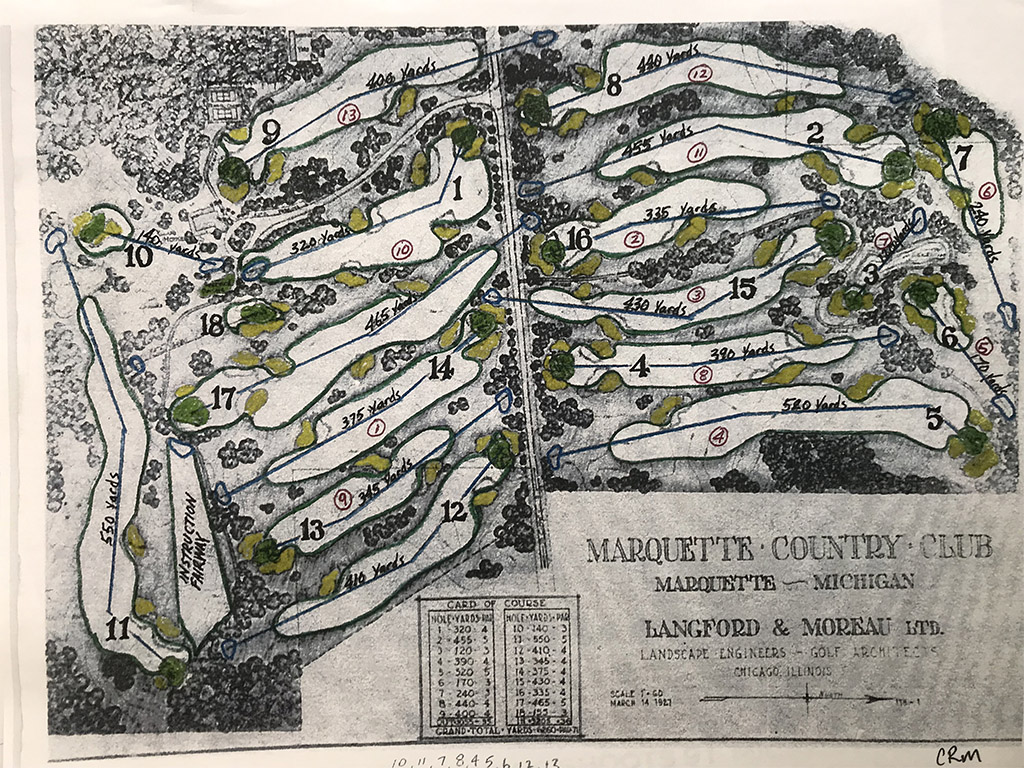

At Marquette Golf Club in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, L&M received sufficient funds to build nine holes in 1930, but they routed an additional nine holes and vowed to come back and build them if golf worked in the area. Unfortunately, the Great Depression hit. Decades later, when Marquette got around to expanding its facility, the L&M plan had been lost, and the club hired David Gill to complete what is now known as the Heritage Course.

Today, the L&M nine remains more or less unchanged, but it is intermixed with Gill’s holes. Years after Gill’s work, Ron Whitten found L&M’s routing plan, leaving us all to dream of what could have been—or perhaps still could be.

Langford & Moreau's original routing plan for Marquette

Legacy

Today, Langford & Moreau are not among the most famous Golden Age golf course architects. They would be even less known, however, if it were not for their influence on Pete and Alice Dye. The Dyes had connections to the L&M-designed Maxinkuckee Country Club, and in their design work, the L&M influence is evident. Look no further than the 4th hole on the Dyes’ River course at Blackwolf Run, a boldly contoured strategic par 4 that could be picked up and placed on an L&M course and look like it had been there forever.

Thinking about Langford & Moreau inevitably evokes a bittersweet feeling. Just because of a few unlucky historical breaks, their legacy is a fraction of what it should be. Since they rose to prominence late in the Golden Age, the Great Depression interrupted their career just as it was taking off. Moreover, when golf development started again after World War II, a new style came into vogue. “Fairness” in golf course design became paramount, and L&M’s giant features often got in trouble with the Fair Police. As a result, many L&M courses either closed or underwent destructive renovations.

Still, it’s a gift that much of the surviving Langford & Moreau portfolio is affordable and publicly accessible, even if it’s compromised. This allows anyone to jump down the L&M rabbit hole and enjoy one of golf’s boldest brewers. Perhaps one day an enhanced understanding and admiration of their work will lead to the preservation or restoration of their remaining courses.

Courses designed by Langford & Moreau (with original features remaining)

Public

Lawsonia Links – Green Lake, WI

Spring Valley CC – Salem, WI

Kankakee Elks CC – Kankakee, IL

Marquette GC (9) – Heritage Course – Marquette, MI

Iron River CC (9) – Iron River, MI

Legacy Hills CC (9) – LaPorte, IN

Maxwellton GC – Syracuse, IN

Harrison Hills GC (8) – Attica, IN

Franklin County CC (9) – West Frankfort, IL

Eglin Air Force Base – Niceville, FL

Private

West Bend CC (9) – West Bend, WI

Ozaukee CC – Mequon, WI

Bryn Mawr CC – Lincolnwood, IL

Culver Academies (9) – Culver, IN

St. Clair CC – Belleville, IL

Milburn CC – Overland Park, KS

Texarkana CC – Texarkana, AR

Skokie CC (8) – Glencoe, IL

Wakonda CC – Des Moines, IA

Innsbrook CC – Merrillville, IN

Minnehaha CC – Sioux Falls, SD

Clovernook CC – Cincinnati, OH

Riverside GC – Riverside IL (pre Moreau partnership)

Clarksdale CC – Clarksdale, MS

Coming soon: The Langford & Moreau Trail…

by

by