Okay, that headline is a little overdramatic. The 13th hole at Augusta National Golf Club is not dead. But over the past 50 years, it has evolved, and the best golfers in the world have started to play it in a fundamentally different way. Not everyone has liked these changes. For those who think the professional game is headed the wrong direction, No. 13 at Augusta National has become, if not Exhibit A, at least Exhibit C or D.

Last week, after going through the annual ritual of downloading the Masters app, I decided to figure out whether I agreed.

Why focus on Augusta’s 13th? If any golf hole deserves to be scrutinized, picked apart, and worried about, it’s this one. Among long holes in championship golf, only No. 18 at Pebble Beach and the Road Hole at the Old Course have anything like its iconic status, or its reputation for strategic soundness. It’s an ideal hole, to dust off an old term.

According to some prominent figures in the golf world, however, No. 13’s greatness is now exactly that: ideal, not real. Time and technology, they say, have left Bobby Jones and Alister MacKenzie’s 1932 design behind.

This opinion seems to be gaining purchase among influential voices at Augusta National. Jack Nicklaus, six-time Masters champion, was blunt in 2017: “In my prime, the 13th was not only one of my favorite holes but was also one of the best in golf. It presented its risks and rewards perfectly. But the golf ball has changed things. If you’re not going to roll back the golf ball, you really need to lengthen the hole by 30 or 40 yards to test the players today.”

Fred Ridley, who became chairman of ANGC four years ago, has repeatedly expressed unease about No. 13. “Admittedly,” he said in 2019, “that hole does not play as it was intended to play by Jones and MacKenzie.”

Recently, the USGA and R&A have begun laying the groundwork for an equipment rollback, which has presumably alleviated some of Nicklaus’s and Ridley’s concerns. Still, Augusta National isn’t taking any chances. In 2017, the club purchased land behind the 13th tee. Nothing but a service road has materialized there so far, but rumors abound.

ANGC's purchase of land from Augusta Country Club entailed a pretty epic tree-removal project pic.twitter.com/ETty9RKKXx

— Garrett Morrison (@gfordgolf) April 7, 2021

With these potential changes looming, I feel it’s time to take stock of what No. 13 at Augusta National truly was and is. There’s a lot of mythology around the hole, and a lot of abstraction in the way we typically discuss it. So I want to be specific about what the intentions of its design were, and how players in the Masters attack the hole differently now than they did in the past. Ultimately, I’d like to know what portion of its original greatness No. 13 still has, if any.

Fortunately, when it comes to Augusta National, plenty of information is available. Maybe—in the case of every-shot coverage on the Masters app—too much. So let’s try to wade in without getting in over our heads.

The concept

Alister MacKenzie’s description of No. 13, published in The American Golfer in 1932 and reprinted in the first Augusta National Invitation program in 1934, is matter-of-fact: “This is played along the course of a brook with the final shot finishing to a green over the stream with a background of a hill slope covered with magnificent pine trees.”

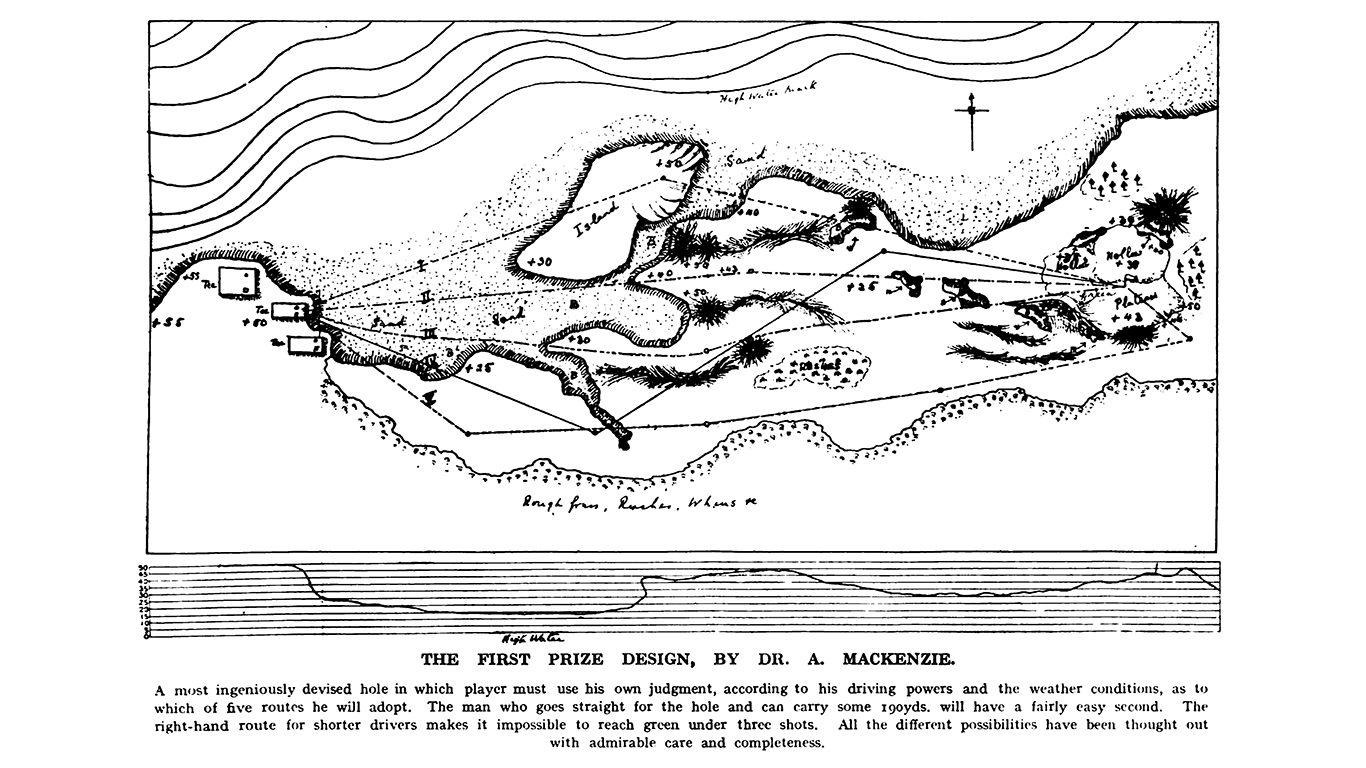

MacKenzie goes on to say that 13th, then the 4th, “has some of the best golfing features of the Seventeenth Hole at Cypress Point, California, and the ideal hole depicted in C.B. Macdonald’s book.” What he calls the “ideal hole” here is apparently the design that won him first prize in a golf architecture competition sponsored by the magazine Country Life in 1914.

-

A map of the 13th hole at Augusta National (Masters.com)

-

Alister MacKenzie's plan for the fantasy hole that won the Lido competition in 1914

-

An aerial of the 17th hole at Cypress Point (Google Earth)

It’s hard to see many specific similarities between No. 13 at Augusta National and either the Country Life hole or the 17th at Cypress Point. But all three have roughly the same strategic concept: a superb natural hazard along one side of the fairway, and a design that maximizes this hazard by offering an advantage—in the form of a shorter, more inviting shot into the green—to the player who flirts with disaster off the tee.

On Augusta’s 13th, Jones and MacKenzie wanted to reward those who had the nerve to work their tee shots right to left, toward the tributary of Rae’s Creek.

This is a risky play, and individual players may decide that the juice isn’t worth the squeeze. But the rewards are clear. “The player is first tempted to dare the creek on his tee shot by playing in close to the corner,” Bobby Jones wrote in his 1960 book Golf Is My Game, “because if he attains his position he has not only shortened the hole, but obtained a more level lie for his second shot. Driving out to the right not only increases the length of the second, but encounters an annoying side-hill lie.”

Jones makes a key point here. The main challenge of No. 13 at Augusta National is not the dogleg, and it’s not the water. It’s the right-to-left slope of the fairway, which becomes less severe as it gets closer to danger. If you bail out right, you’ll have to play your second shot from the side of the hill; if you keep tight to the corner, you’ll get more of a driving-range lie.

The final brilliant element of the 13th hole is the angle of the green and its surrounding hazards. From the preferred left side of the fairway, the green is deep and the water runs more or less parallel to the line of play on the right. From the tilted right side of the fairway, the green and hazard run on a diagonal from low left to high right, clashing with the ball flight that the sidehill lie promotes.

The desirable (yellow) and less desirable (red) lines into the 13th green at Augusta National (Google Earth)

On The Fried Egg podcast, Geoff Ogilvy explained the difficulty of this approach shot better than I could: “If it was a flat lie, you’d want to hit a fade into that green, because you could hit a shot that was basically never [at risk] of going in the water. You could start it left of the green, the shortest carry [over the brook]. You could hit a safe one and say, ‘Well, if I hit it straight, I’ll just miss the green left and I can kind of birdie from over there.’ But you have to, with the ball above your feet [for a right-hander], kind of hit a draw. So you’re hanging it over the long carry, and you’re hanging it over the water. You’ve got this shot where all you want to do is hit a high fade and all the stance wants to give you is a low draw.”

So what persuades you to lay up on No. 13 is not just the length of the carry; it’s the awkward fit between the right-to-left canted fairway and the left-to-right angled green. This is why the second shot sometimes entails a “momentous decision,” to use Bobby Jones’s famous phrase.

The beauty of Jones and MacKenzie’s 1932 design was that it didn’t need a lot of artificial hazards. If players wanted to smash one into the field on the right, fine. They would have little chance of reaching the green from there, especially with the equipment of the day. They were welcome to punch one down in front of the tributary and make a 5 or, with an unusually precise pitch, a 4. But most birdies and eagles, as well as most double and triples, would be reserved for those who played courageously (foolishly?) off the tee.

13th tee Augusta National- approx 60 years ago pic.twitter.com/ber1qjIpGO

— Bradley Hughes (@bhughesgolf) December 4, 2018

A “really great course,” MacKenzie wrote in 1932, “must give the average player a fair chance, and at the same time… must require the utmost from the expert who tries for sub-par scores.” That’s the original 13th in a nutshell. For the average player, a par or bogey was achievable; for the Masters competitor, a birdie was a tall order, and a championship-wrecking score was a possibility.

“It’s probably the perfect golf hole,” Geoff Ogilvy said, “and if it isn’t the perfect golf hole, it’s as close as you can get.”

Gradually, then suddenly

Every April, I revisit Ron Whitten’s “Comprehensive History of Every Change Made to Augusta National Golf Club” on the Golf Digest website. You should, too. It’s a remarkable feat of research and a useful reminder of how different today’s Augusta National is from its earliest incarnations. What Whitten reveals about No. 13 in particular is illuminating, though not surprising: the hole’s evolution has been all about trees. (As you read the next few paragraphs, I would recommend following along with Golf Digest’s historical maps of the 13th.)

In 1934, only a handful of trees were really in play. A few on the inside corner of the dogleg prevented long hitters from taking the shortcut, and a pair in the middle of the corridor served as a starting-line reference and an additional bit of trouble for those who hedged right.

A 1933 aerial of Augusta National. The 13th fairway is visible along the bottom; note the relative lack of trees along its right side.

By the mid-70s, the tree lines had filled in on both sides. Going right of the centerline sentinels was no longer a viable option, but the hole was still wide. Also, at 485 yards, it was long enough to lure players close to the stream in pursuit of a less daunting second shot. Its strategic identity intact, No. 13 remained more or less the same between the 70s and the late 90s. Watch any Masters telecast from this period and you will see player after player hooking their drives around the corner and ending up on the flat next to the water. This Tom Watson drive from 1991 is a good example. Look at that ball dart left!

Every year, it was one of the most spine-tingling shots to see the pros attempt, up there with the tee shot on 12 and the approach to 15.

But then 1997 happened. On his way to an era-defining 12-shot victory, Tiger Woods played the 13th hole differently than anyone else. He not only hit his drive farther, but he also sent it well away from the brook, toward the top of the hillside. Why? He had such a short approach that the sidehill lie wasn’t much of a threat. On Sunday, his smooth 30-degree 5-iron to the middle of the green almost looked easy.

What was striking about Tiger’s final-round performance on No. 13 wasn’t just the power and purity of the strikes, or the way he reduced the hole to a mid-length par 4. It was that everything he did felt safe. His drive was never in danger of going in the water, and his approach flew high, landed soft, and left plenty of room for error. Neither shot seemed risky for him. And this hole was supposed to be all about risk, all about the potential for catastrophe.

Granted, no one but Tiger Woods could hit these shots in 1997. At the next year’s Masters, we saw Fred Couples puring a long iron from the traditional garden spot next to the stream, and eventual champion Mark O’Meara playing from a similar position on Sunday. Unlike Tiger, Couples and O’Meara didn’t have the length to ignore the offer of a decent lie and angle.

Mark O'Meara enjoying a relatively flat lie in the 13th fairway at the 1998 Masters

Soon that would change. In the late 90s and early 00s, the pros began showing up at Augusta National with newfangled equipment: drivers with 460cc titanium heads, balls with solid cores and urethane covers, even hybrids and utility irons. More and more players became capable of dismantling the 13th hole the way Tiger Woods did in 1997, hitting it far enough off the tee so that being on the safe side of the fairway wasn’t a huge problem. The green jackets didn’t like what they were seeing.

At the 2002 Masters, ANGC unveiled a new tee on No. 13, stretching the hole from 485 to 510 yards. But the more consequential changes had started earlier. In the late 90s, the club began filling the right half of the playing corridor with trees, creating a bottleneck about 270 yards off the tee. The edge of the fairway gradually crept down the hillside, and a carpet of pine straw appeared under the now-dense canopy of trees. What had been an open field in 1932 was now a slim, left-turning passageway through the woods.

-

Costantino Rocca on the 13th tee at the 1997 Masters

-

Hideki Matsuyama on the 13th tee at the 2021 Masters

Before the era of Tiger Woods and the Pro V1, players had willingly hit hooks around the corner. Now the hole would make them do so.

The 2021 Masters

My first impression of No. 13 at this year’s Masters was that it had lost a lot of subtlety in its presentation. It used to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing: a hillside, a brook, and a well-guarded green—that was all. You were free to negotiate these simple elements however you wanted. But if you tried to make a birdie, you could suddenly find yourself in the wolf’s stomach. Nowadays, the 13th is less tantalizing than it is straightforwardly intimidating. Trees loom on both sides.

The more every-shot coverage I saw, though, the more I realized that the hole isn’t one-dimensional, exactly. Its challenges have just become different.

For modern pros, the main trouble is the tight, awkward tee shot. If you hit it on a straight line more than 260 yards—which every realistic contender in the Masters does with every club stronger than a long iron—you will run through the fairway, likely into the trees and pine straw beyond. If you attempt to cut the corner with a straight ball, you will get knocked down by the trees on the left, potentially into the stream. So in order to get within comfortable striking distance of the green (about 225 yards for elite players), you need to shape your tee shot from right to left.

This is not the most natural thing for a 21st-century right-handed pro to do. Modern driver heads are not easy to turn over, and modern balls are optimized for low spin off of long clubs, so a lot of current pros simply don’t have a 300-yard hook in their repertoire.

Consider the adventures of Gary Woodland and Jon Rahm, both right-handed power faders, on No. 13 in 2021. These guys don’t stink; Woodland is a major champion and Rahm is, by some measures, the best golfer in the world. Yet neither seemed able to produce the required right-to-left ball flight on the 13th. On three of four attempts, both left their drives hanging out to the right. In the third round, Rahm tried to force one over the left corner, and the trees got in the way. “You just can’t do it on this hole, huh?” he muttered to himself.

There is entertainment value in seeing players grapple with a shot that sets up poorly for them. They’re forced to try different things. Last week, many right-handers went with a fairway wood, perhaps finding it easier to hit a draw with a smaller head and a higher loft. Others, including Bryson DeChambeau, smashed it over the trees on the left in hopes of sneaking past the ones on the right. On Sunday, this play worked out beautifully for DeChambeau, leading to a 160-yard approach and an eagle. But on the other three days, he missed his target slightly right and ended up bedeviled by a copse of trees next to the 14th fairway. “That’s so far into Narnia,” he said of his third-round effort. (A bad thing, evidently.)

Left-handers had an obvious advantage. Setting up with their feet outside the right-hand tee marker, they could swing freely with a driver and rip a slider down the corridor. On Thursday and Friday, all six lefties in the field birdied the 13th hole both times. Young Robert MacIntyre’s tee shots were particularly strong; you just don’t see many right-handers replicating those lines.

The path of Robert MacIntyre's first-round birdie on the 13th hole at the 2021 Masters (Masters.com)

So No. 13 still puts a premium on a right-to-left shape off the tee. But that’s the only major aspect of the hole’s original strategy that has survived.

First, if today’s Masters competitors hit something resembling the tee shot they intend, they’re going for the green in two, no question. The “momentous decision” Bobby Jones wrote about has become a rarity. Second, almost no one seems interested in flirting with the brook. Today’s pros aren’t looking for a flat lie on No. 13; they’re hoping to get all the way out of the chute, into an expanse of fairway that hardly anyone could reach 30 years ago.

The rule-proving exceptions last week were Abraham Ancer and Justin Thomas, both of whom played old-fashioned hooks on the 13th hole. Ancer’s second-round drive even got fairly close to the water, but it was Thomas’s scimitar Protracer that went semi-viral on Friday.

😷😷😷 pic.twitter.com/c7UH7YVvZB

— Ryan Lavner (@RyanLavnerGC) April 9, 2021

The risk of JT’s play became apparent on the weekend, however. On Saturday, his hook didn’t hook; on Sunday, it hooked too much.

Either way, the Ancer/Thomas line on No. 13 was a fun throwback, a reminder of what the hole used to persuade almost every player to do.

Routine changes

The story of Augusta’s 13th may turn out to be a Rohrschach test. If you enjoy the modern pro game, you might point out that the changes have allowed the hole to remain a relevant test. To this day, it forces the world’s best players out of their comfort zones and rewards well-planned, well-executed shots. But if you’re a devotee of Golden Age golf architecture, you might focus on what the hole has lost. It used to be a simple-looking par 4.5 that gave you options but tempted you to try something crazy. Now it’s a tough-looking par 4.5 that shows you the line and asks whether you have the guts to follow it.

The same debate can be had about several holes at Augusta National. Nos. 11, 15, and 17, too, have been lengthened and narrowed. In each case, it’s the same story: Jones and MacKenzie intended to test driving accuracy with greens that accepted aggressive approaches only from certain angles, but as hitting distances increased, players didn’t have to worry as much about where in the fairway their tee shots settled. They weren’t running long irons through gaps anymore; they were using high-lofted clubs to stick their approaches on shelves, and usually they could do that just as well from one side of the fairway as the other. So to maintain some emphasis on driving accuracy, ANGC added tees and trees, trees and tees. Again. And again.

Dear Augusta National,

Please restore the 11th hole. pic.twitter.com/Yz6h59kaMr

— The Fried Egg (@the_fried_egg) April 11, 2021

More change is on the way for No. 13. According to Luke Donald, the hole could have a new back tee as early as next year. And I wouldn’t be surprised if that tee were as far left as possible, so as to prevent the big boys from flying the dogleg.

As always, the impact of these tweaks will be excellent nerd bait. No doubt next year I’ll watch another 300-some drives on No. 13 and make a big deal out of every small shift in tactics. Then I’ll dive back into the broadcast archive and be struck again by the beautiful lines Seve Ballesteros and Ben Crenshaw took with their persimmon woods and spinny wound balls. This has become part of the routine of my Masters weeks. I don’t find it unpleasant.

Here’s another routine, and one that I don’t see stopping anytime soon: Chairman Fred Ridley, at his annual press conference, talking about updating the 13th hole to defend the integrity of its original design. I always wonder what objective he has in mind. Moving the tee back and to the left would likely result in higher scores and fewer greens hit in two. Perhaps we’d see “momentous decisions” from the fairway slightly more often. That would be an improvement.

But if the goal is to restore Jones and MacKenzie’s intentions on No. 13, there’s really just one indicator of success: a Sunday tee shot landing on the side slope and rolling down toward the water, risking disaster for a chance at glory.

More Masters coverage from The Fried Egg team:

Is Augusta National Turning Over a New Leaf?

Geoff Ogilvy’s notes on all 18 at Augusta National

Stories worth your time and tracking at the 2022 Masters

The Art Behind Augusta’s Roars: Focal points in Alister MacKenzie’s routings

Tiger’s Masters flirtation is something more than ceremonial

by

by