Royal Melbourne (West Course)

The combination of a fully realized Alister MacKenzie design and an exceptional piece of land makes Royal Melbourne West a contender for best course in the world

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Alister MacKenzie (original design, 1931)

Private

$$$$

The Australian Sandbelt in the Spotlight

Michael Clayton Talks Royal Melbourne (Great Courses 4)

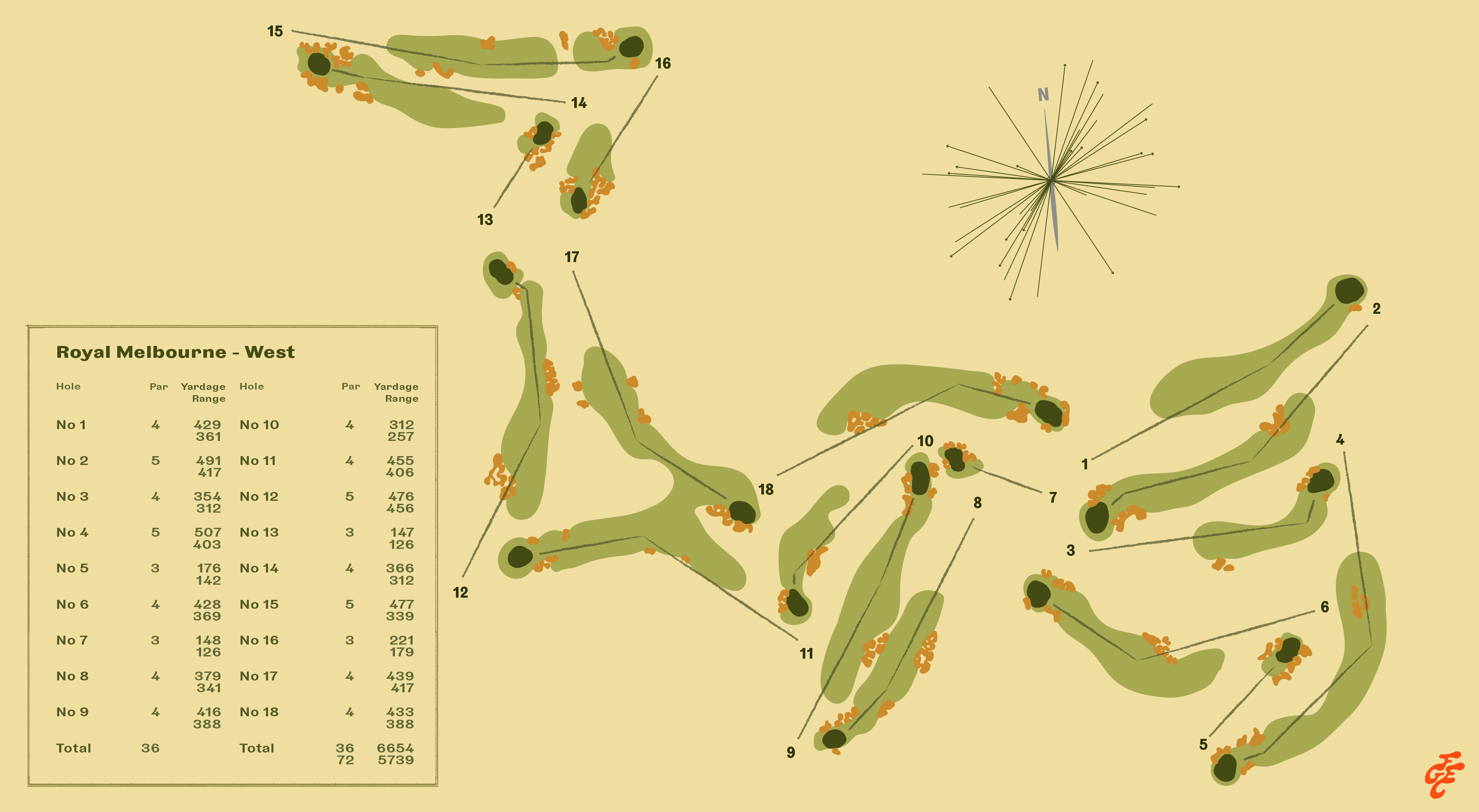

The West Course at Royal Melbourne Golf Club has two main advantages over the Melbourne Sandbelt’s many other excellent golf courses: 1) it received the lion’s share of architect Alister MacKenzie’s attention during his visit to Australia in 1926, and 2) it sits on the most dramatic topography in the area. The combination of a fully realized MacKenzie design and an exceptional piece of land — along with world-class turf conditions — makes Royal Melbourne West a contender for the best course in the world.

Like many of Melbourne’s top golf clubs, Royal Melbourne was founded in the 1890s at a location near the city center, but it moved south in the early 20th century to escape urbanization and find better land. In 1926, the club hired Alister MacKenzie, then best known for his association with the R&A, to design a new course on a sandy, rolling property in the suburb of Black Rock. MacKenzie arrived in Melbourne in late October 1926 and spent about a month laying out holes at Royal Melbourne and moonlighting as a consultant at other clubs in the region. After he left, Alex Russell, a club member and accomplished amateur player, supervised the long, difficult construction process. Russell, with the help of head greenkeeper Mick Morcom, completed the West and East courses at Royal Melbourne in 1931 and 1932, respectively.

The two courses complement each other well, seamlessly melding into a Composite Course for big tournaments. The West stands out, however, for its bold use of large-scale landforms and its broad, often viciously tilted greens. The course’s big, billowing, crisp-edged bunkers — positioned to provoke thought rather than merely to punish poor strikes — established a template that nearly every other notable Melbourne golf club has since followed. Best of all, the course has not been substantially altered since Russell finished it. Thanks to Royal Melbourne’s lineage of long-tenured superintendents, as well as to light-touch restoration work by Tom Doak, the West Course is one of the world's best-preserved examples of Golden Age golf architecture.

Take Note...

The old ways. Mick Morcom seeded the original putting surfaces at Royal Melbourne with a rare cultivar of bentgrass called Sutton’s Mix. This turf — which, according to historian Neil Crafter, may have contained some fescue — thrived for the next several decades. In the 1980s, however, the club decided to re-sod the greens with a more up-to-date varietal, Penncross bentgrass, in an effort to modernize playing conditions and aesthetics. But by the late 90s, the Penncross experiment had already run its course, and Royal Melbourne was busy converting its putting surfaces back to Sutton’s Mix. Sometimes the old ways are the best.

The ground game. First-time visitors to Royal Melbourne may be surprised to find that the grass immediately around the greens is a different color from both the Bermudagrass of the fairways and the Sutton’s Mix of the putting surfaces. That’s because it’s fescue. Royal Melbourne uses this firm turf type for its green surrounds in order to allow players to hit low, running approach shots.

Gathering points. Like MacKenzie’s Augusta National, Royal Melbourne is a top-tier spectator venue. This is partly because of the intimate, interlocking routings of the West and Composite courses, which create hubs of activity where multiple holes converge. If you go to a tournament at Royal Melbourne, I especially recommend standing on the hill by the seventh green on the West Course, where you’ll be able to watch action on the eighth, ninth, 10th, and 18th holes on the West as well as the first hole on the East. (The numbering for the Composite Course will be different, obviously.)

{{content-block-course-profile-royal-melbourne-west-001}}

Favorite Hole

No. 3, par 4, 354 yards

At first glance, the third hole at Royal Melbourne seems simple, even plain. The fairway is unguarded aside from a pair of bunkers off to the right, about 200 yards from the back tee. Proficient players may not even notice these.

The strategic game of the hole is governed by the green, which slopes substantially from front to back. Swing your tee shot out to the right — ideally to the elbow of the dogleg — and your approach will play across this slope rather than down it. If you go for the green and come up short in the scabby rough, however, you will face a tricky recovery to a target that runs away from you.

A knowledgeable player in my group told me that the third fairway used to extend farther out to the right, where the club currently maintains an irrigation pond. Perhaps, then, the fairway bunkers I mentioned earlier once had a clearer strategic purpose: you could carry them to attain an advantageous angle of approach from the right. That angle is still available, but not as generously so.

The third green, too, seems simple initially, falling away at a steady clip. But closer inspection reveals an array of intricacies: the undulations within the fronting swale, which send running approaches in unpredictable directions; the small but sharp falloff in the back; the two bunkers eating into the left side of the green, and the variety of faint ripples in the putting surface, which generate hard-to-read breaks. While covering the Sandbelt Invitational last December, I spent about 10 minutes lingering around and taking photos of this green, never quite feeling that I understood everything about it. The upshot of its design is simple, though: as short as your approach on the third hole might be, you will have tremendous difficulty getting close to any pin because of the green’s tilt and sneaky intricacy.

{{royal-melbourne-west-favorite-hole-3-gallery}}

Favorite Hole

No. 3, par 4, 354 yards

At first glance, the third hole at Royal Melbourne seems simple, even plain. The fairway is unguarded aside from a pair of bunkers off to the right, about 200 yards from the back tee. Proficient players won't worry about these.

The strategic game of the hole is governed by the green, which slopes substantially from front to back. Swing your tee shot out to the right — ideally to the elbow of the dogleg — and your approach will play across this slope rather than down it. If you go for the green and come up short, however, you will face a tricky recovery from scabby rough to a target that runs away from you.

A knowledgeable player in my group told me that the third fairway used to extend farther out to the right, where the club currently maintains an irrigation pond. So perhaps the fairway bunkers I mentioned earlier once had a clearer strategic purpose: you could carry them to attain an advantageous angle of approach from the right. That angle is still available, but not as generously so.

The third green, too, seems straightforward initially, falling away at a steady clip. But closer inspection reveals an array of intricacies: the undulations within the fronting swale, which send running approaches in unpredictable directions; the small but sharp falloff in the back; the two bunkers eating into the left side of the green; and the variety of faint ripples in the putting surface, which generate hard-to-read breaks.

While covering the Sandbelt Invitational last December, I spent about 10 minutes lingering around and taking photos of this green, never quite feeling that I understood everything about it. The upshot of its design is simple, though: as short as your approach on the third hole might be, you'll have trouble getting close to any pin because of the green’s tilt and sneaky complexity.

{{royal-melbourne-west-favorite-hole-3-gallery}}

Overall Thoughts

When Alister MacKenzie arrived in Melbourne, Australia, in October 1926, he was not yet Alister MacKenzie. While he had done some skillful and eye-catching architectural work at Alwoodley, Moortown, Sitwell Park, and other courses in Great Britain and Ireland, he had not yet created the American masterpieces that now define his legacy. Even the leaders of Royal Melbourne Golf Club, who had paid for him to make the month-long journey from his home in England across the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, seemed not to have much familiarity with him. They had wanted to hire Harry Colt. They were simply trusting Colt’s word that MacKenzie was the next best thing.

What MacKenzie had done, however, was write a book explaining his ideas about golf course design. Like many upstart golf architects before and since, he established his authority in the profession more with the pen than with the shovel. And MacKenzie’s words were potent. In Golf Architecture, published in 1920, he set forth a philosophy that revolutionized Australian golf and turned Melbourne into one of the game’s meccas. It’s a remarkable story, considering he spent only 10 weeks on the continent.

As a theorist, MacKenzie was the descendant of two innovators. First, he followed writer and R&A member John Low’s prescriptions for hazard placement. Low argued, and MacKenzie agreed, that 1) no hazard is “unfair” wherever it's placed because, as MacKenzie put it in Golf Architecture, “it should be obvious that if a player sees a hazard in front of him and promptly planks his ball into it he has chosen the wrong spot”; and 2) the purpose of a hazard is not to punish a poor shot by a poor player, but rather to thwart a nearly great shot by a proficient player, making the game more engaging for the skilled and less arduous for the hapless.

Second, MacKenzie endorsed his friend and former design partner Harry Colt’s approach to construction, which emphasized naturalism and the blending of manufactured landforms into preexisting terrain. “The [ideal] course should have beautiful surroundings,” MacKenzie declared in his book, “and all the artificial features should have so natural an appearance that a stranger is unable to distinguish them from nature itself.”

MacKenzie brought these cutting-edge theories to Australia, not only through his own, voluble conversation, but also in the many copies of Golf Architecture that he distributed among Royal Melbourne members. “The way he thought about golf was what formed golf here,” Mike Clayton, architect and Melbourne native, told me in 2024. Among MacKenzie’s keenest students were local landowner Alex Russell and greenkeeper Mick Morcom, who ended up carrying out MacKenzie’s plans for Royal Melbourne West between 1926 and 1931.

The West embodies the Low school of strategic design as faithfully as any course in the world. Large, intimidating bunkers guard the ideal positions in the fairways of par 4s and 5s. Greens tilt away from bail-out zones and toward lines of charm. Subtle but complex green contouring creates pin positions of differing intensities and strategic implications.

The course's opening sequence is astounding: a series of doglegging par 4s and 5s, with one par 3, the famous fifth, mixed in. Each hole is more striking than the last. The first is the plainest, curving left around motley rough and a grove of tea trees to a simple green enlivened by a gully at its front-left corner. The short par-5 second introduces some drama, with a huge, flashed bunker protecting the inside of the dogleg and two more, built in the same grand style, creating a right-to-left entrance into the elevated green. No. 3, profiled in the “Favorite Hole” section above, is an introverted, beguiling short par 4, followed by an extroverted par 5 that vaults up and over a cluster of bunkers cut into a ridge, then swerves to the right to find a green tucked into a grove of trees. Those who take on the center-line bunkers and succeed earn a forward kick and a much-improved chance of reaching the green in two. The par-3 fifth plays over a small valley and up a large dune to a terrifyingly tilted green surrounded by a gorgeous arrangement of bunkers and tie-ins. Finally, the par-4 sixth, featured on many lists of the world’s best holes (including the one in my dog-eared 1980s copy of The New World Atlas of Golf), dares players to challenge the long-right side of a diagonal stretch of scrub and bunkers in hopes of attaining an angle into, rather than across, the severe slope of the putting surface.

{{royal-melbourne-west-opening-sequence-gallery}}

As he does after the duneland stretch of Nos. 6-9 at Cypress Point, MacKenzie brings the temperature down after a hot start at Royal Melbourne West. The eighth and ninth holes play out and back along tumbling terrain — good holes, but not mind-melting. Quickly, however, he hits another high: No. 10 is a superb short par 4 with a huge blow-out bunker standing sentinel on the direct line to the small, perched green. Clayton likes to reminisce about watching Seve Ballesteros attack this hole during the 1978 Australian PGA Championship. With all of his competitors laying up, Seve went straight for the green every day, making three birdies.

The West Course's primary weakness lies across Cheltenham Road, where Nos. 13-16 sit. Flatter land means less excitement, and Nos. 14 and 15, both pressed against property lines, are the only holes on the course that feel artificially constrained. Even on this separate and inferior paddock, however, there are moments of brilliance: see the fascinating contouring and extravagant bunkering around the 13th and 14th greens, or the overall excellence of the 16th hole, one of the finest long par 3s I’ve played.

{{royal-melbourne-weak-stretch-bright-spots-gallery}}

Still, it was clever of MacKenzie to save one last patch of outstanding ground for the 17th and 18th holes, a pair of emblematic Royal Melbourne par 4s. Both tempt players to save their rounds or catch up in their matches by taking treacherous shortcuts along the insides of the doglegs.

{{royal-melbourne-west-17-18-gallery}}

Indeed, Royal Melbourne West is MacKenzie’s love letter to the dogleg hole. Only four of the course’s 14 non-par 3s don’t bend significantly in one direction or the other. It should be clear why MacKenzie liked doglegs: almost by definition, they generate forgiveness for lesser golfers, who can bunt their drives out to the fairway before the turn, and challenge for expert players, who must decide whether and how much to cheat the corner.

The West Course also exemplifies MacKenzie’s knock for maximizing a property’s most prominent and beautiful natural landforms. The center of Royal Melbourne’s main paddock is dominated by a rise that could be called either a small hill or a large knoll, and the opening half of MacKenzie’s routing makes a Michelin-starred meal out of it. The first, third, eighth, and 10th holes play off of it; the second, sixth, and ninth holes play into it; and the par-3 seventh hole climbs to its peak. The course then wanders into quieter terrain before returning to the central knoll on Nos. 17 and 18 — the 17th green is nestled into the base of the hill, and the 18th hole wraps around its shoulder.

This focal point of the West Course’s routing casts the property in a flattering light. By using one stellar topographical feature in many different ways, MacKenzie fools the golfer into believing that the land contains more variety than it actually does. (He pulls off the same trick at Cypress Point, Augusta National, and nearly all of his other courses from the mid-1920s on.)

So yes, MacKenzie deserves enormous credit for importing state-of-the-art British ideas about golf course design to Australia in general and Royal Melbourne in particular. But what makes the West Course unique is not architecture alone; it is the combination of architecture and stewardship. Royal Melbourne’s superintendents, from Mick Morcom to Claude Crockford to today’s Richard Forsyth, have hewed closely to MacKenzie's founding principles of links-like strategy and naturalism. They have prioritized firmness over lushness, patina over high-tech agronomics, tawny natives over foreign greenery. They have taken pains to retain the sizes and shapes of the sinuous bunkers designed by MacKenzie and constructed by Russell and Morcom. They have forestalled the inward creep of mowing lines. In recent years, Forsyth and consulting architect Tom Doak have focused on vegetation management, removing trees that were added in the mid-1900s and restoring indigenous heath. Forsyth and Doak still have work to do on this front, but they have made admirable headway so far.

At Royal Melbourne, the theories of Golden Age golf architecture are not merely theoretical; they come to life with the lively bounce and roll of the ball. Except in extreme cases, the West Course is not vulnerable to a thoughtless aerial attack. If you want an advantage, you have to take on some risk. And that’s one reason why Royal Melbourne West is among the small handful of legitimate candidates for the title of greatest golf course in the world.

3 Eggs

The West Course at Royal Melbourne is the epitome of a three-Egg course. Its land, design, and presentation are all supreme.

Course Tour

{{royal-melbourne-west-course-tour-01}}

Drone photos were taken by Will Watt of Contours Golf

Additional Content

Great Courses 4: Michael Clayton Talks Royal Melbourne (Fried Egg Golf Podcast)

Regions of Golf: The Melbourne Sandbelt (Designing Golf Podcast)

Leave a comment or start a discussion

Get full access to exclusive benefits from Fried Egg Golf

- Member-only content

- Community discussions forums

- Member-only experiences and early access to events

Leave a comment or start a discussion

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere. uis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.