It has been a week since Gary Woodland stomped on his competitors’ throats and took home his first career major. What a U.S. Open! Now that the post-Pebble hangover has worn off, I’ve put together a few reflections on the month in golf. Topics include Woodland’s strengths and weaknesses, Brooks Koepka’s aura, Pebble Beach’s narrow fairways, and the challenges of being fresh out of college and on the PGA Tour.

A ball-striking machine

For me, the lasting memory from the 2019 U.S. Open will be that Gary Woodland won in emphatic fashion with his putting and chipping, which are exactly the skills that have let him down in the past.

Golf is about failing 99% of the time, and no one knows that better than Woodland. In recent times, few players in the world have contended as much as he has and won as little. Since 2016, Woodland has finished in the top 25 in 45% of his PGA Tour starts. Unfortunately for him, tour golf rewards sporadic flurries of brilliant play more than it does a steady march of top 10 performances.

So after Woodland’s win at Pebble, the big question is whether he will go from habitual contender to regular winner. His past stats suggest he won’t—but with slight improvement in two areas, he could become a dominant force.

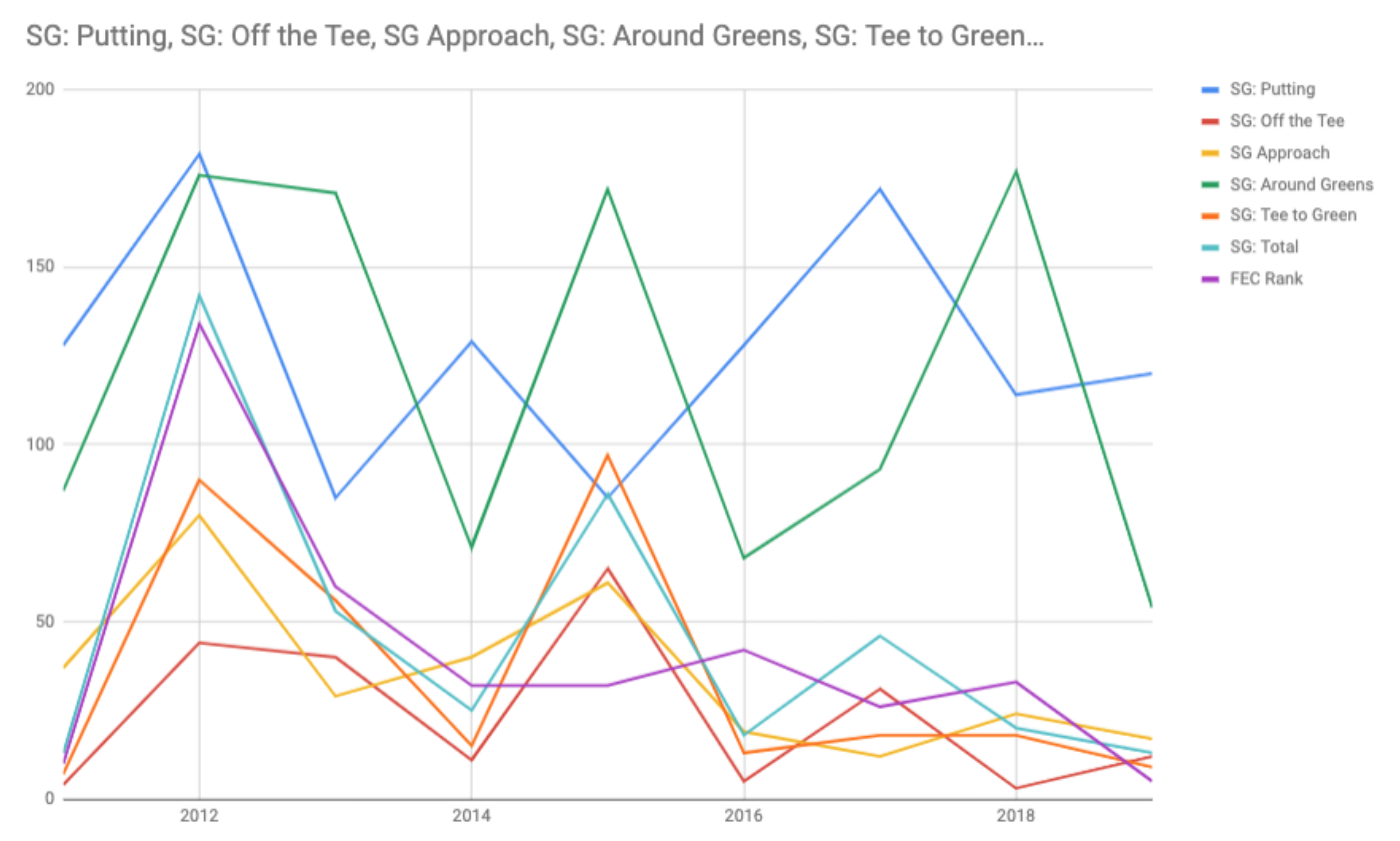

At the U.S. Open, Woodland capitalized on a great putting week, and in general he tends to win whenever he putts well. To date he has won four PGA Tour events, and on each occasion he had a stellar week on the greens. We have Shotlink data for three of his wins. Of those, his worst performance in Strokes Gained: Putting was 16th; last week, he ranked second in that category. This is far from Woodland’s norm on the greens. Since 2011, he has averaged 127th on tour in SG: Putting and 119th in SG: Around-the-Green. During the same span, his tee-to-green game has been stellar, with a median rank of 12th in SG: Off-the-Tee and 29th in SG: Approach. Because of this ball-striking prowess, Woodland has finished outside the top 60 in the FedEx Cup only once since 2011 and outside the top 42 just twice.

Gary Woodland's relative strokes-gained performance over time

Woodland’s best season on the greens was 2015, when he ranked him 85th on tour in SG: Putting. It’s a similar story around the greens: his best season-long ranking in the short-game statistic 68th in 2014. Not coincidentally, Woodland has fared better in SG: Around-the-Green so far in 2019: he is currently 54th. This small bump, along with career-best SG: Tee-to-Green and Total ranks, likely accounts for much of his success this season.

If he can become just average on and around the greens, Woodland will be an elite player on the PGA Tour. In 2018, for instance, Woodland gained .07 strokes putting and lost .227 around the greens. Had these numbers both been simply the tour average, he would have gone from 20th to 13th in SG: Total. This difference divides players who win a lot from those who merely contend a lot.

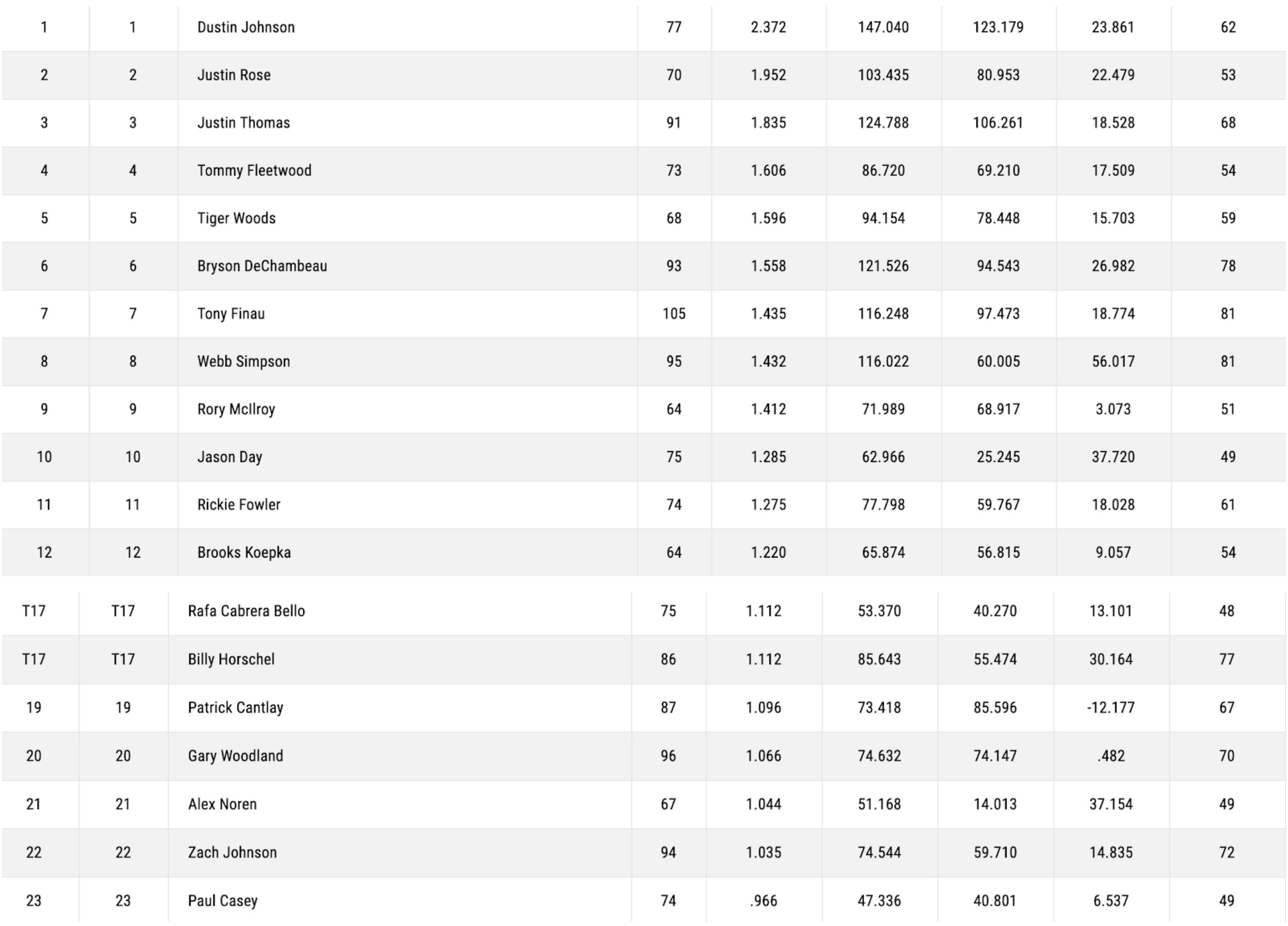

2019 Strokes Gained: Total ranking

For a 35-year-old pro like Gary Woodland, it’s easier said than done to acquire new golf skills. But I’m rooting for him to do so. His ball-striking is built to rack up majors, and he’s one of the most likeable and marketable players out there. It’s an indication of the respect he has earned on tour that, after his U.S. Open win, a large group of his competitors greeted him and celebrated with him. So here’s hoping Woodland can be just an average putter and chipper. That’s not too much to ask, is it?

The air of inevitability

Speaking of games built for major championships, Brooksy impressed again. There isn’t much to say that hasn’t already been said. Clearly we are witnessing a historic run. Since the wrist injury that sidelined him at the beginning of 2018, he has notched three wins, two runner-ups, and a T-39 (in last year’s Open) in six major starts.

What stood out to me on Sunday at Pebble Beach was the air of inevitability. Everyone on the grounds felt that a Koepka surge would come—and it did, as he birdied four of his first five. For a moment, it seemed Tiger-like. But Woodland had his own fantastic round on Sunday. He answered Brooks’s runs and kept him at arm’s length.

Regardless, Koepka has established a presence in big tournaments that we have seen only in a few players. When the conditions get tough, he knows he’s the best and so do his peers. It’s an aura no one has been able to sustain since Tiger did for a decade. At Pebble, the only thing that kept Brooks from a three-peat was his mediocre week on the greens. While Woodland gained over eight shots putting, Brooks picked up just 0.24. It’s scary to think that even though he didn’t have his best stuff, Koepka got beaten by only one player.

Save the drama for your mama—or, wider pastures

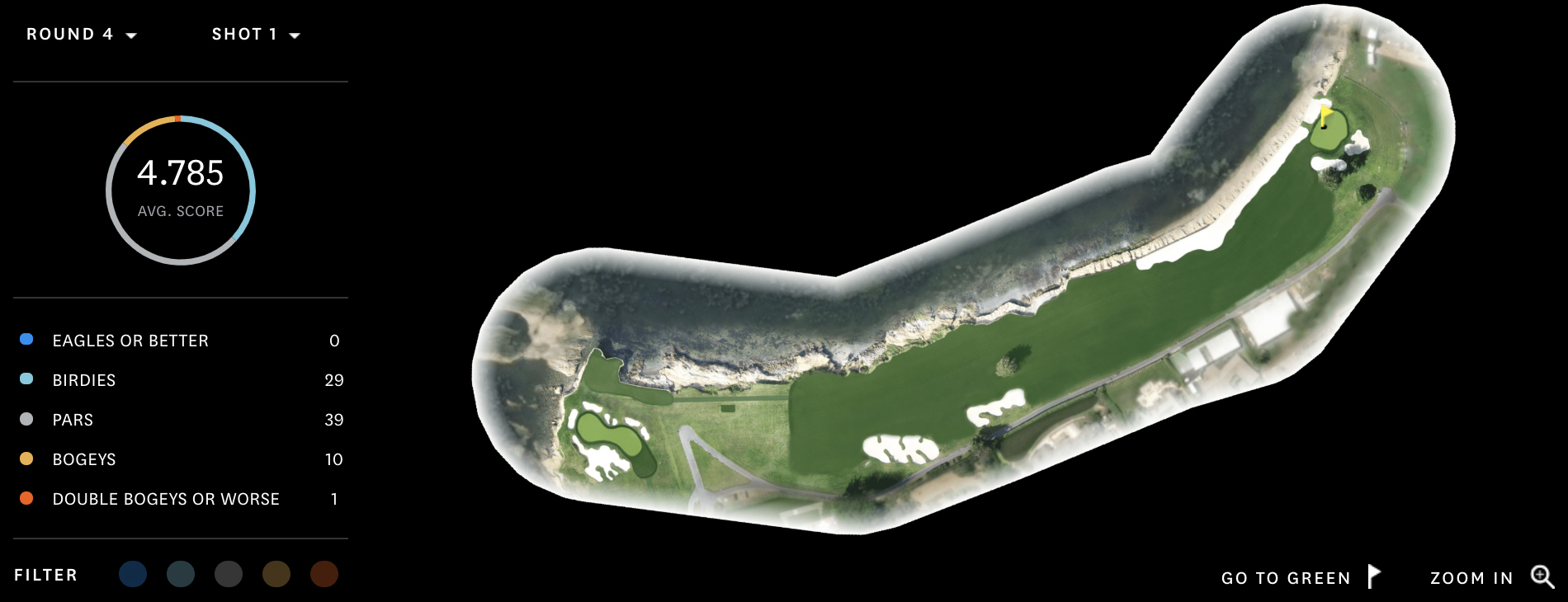

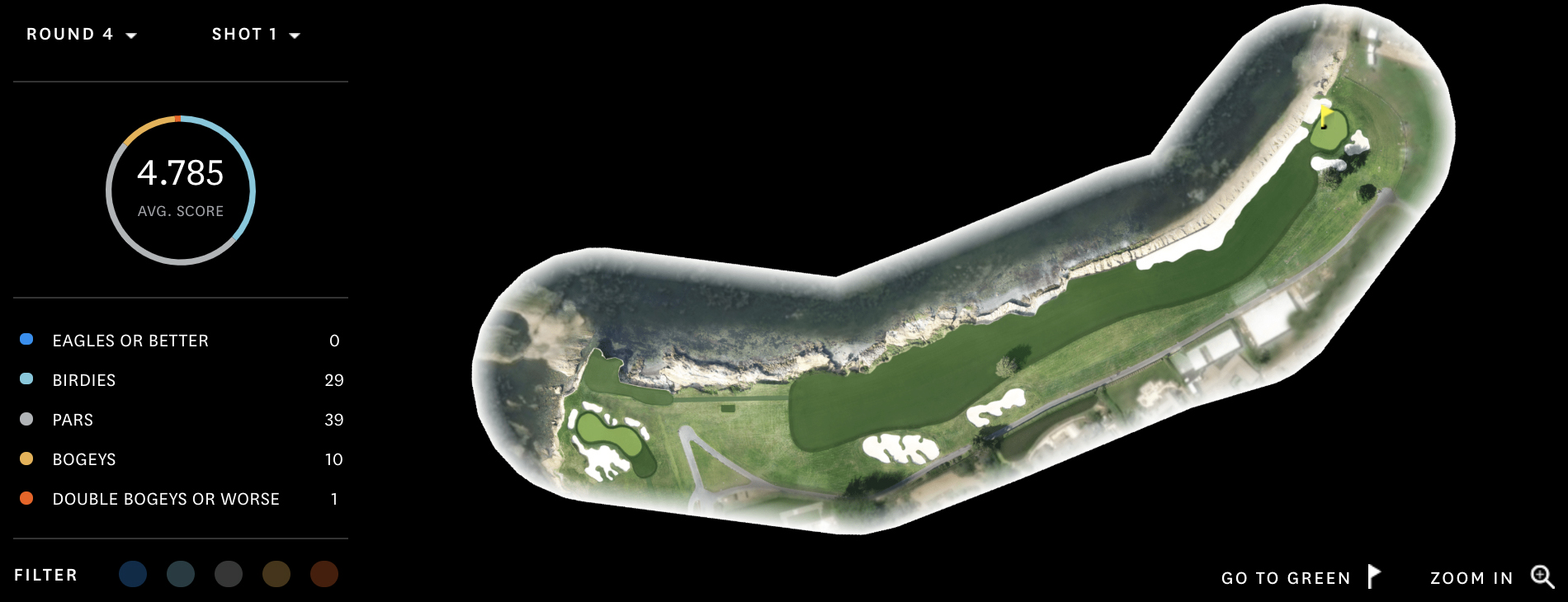

The USGA nailed the setup at Pebble Beach during tournament week, a much-needed win for the oft-criticized organization. The decision to narrow Pebble Beach’s fairways, however, diminished the event’s drama.

On Nos. 4, 11, 16 and 18, the tighter fairways were particularly noticeable and took away the disadvantaged angles. The changes at the 18th in particular might have robbed Sunday of some drama. The hole’s narrowness led to most of the biggest hitters throttling back to 3-wood on the iconic tee shot.

Brooks Koepka, for instance, opted for 3-wood all week. On Sunday, he roped a draw up the gut but left himself between his 3- and 4-iron distances. Unable to use a higher trajectory, his shot bounced over the green. Had the width of the 18th hole been retained, Koepka would likely have hit driver, leaving a shorter approach and a better chance at an eagle and a tie with Woodland. Obviously this is all hypothetical, but it’s just one example of how much less interesting 25-yard wide fairways are. They force everyone to play the same, even on some of the world’s most dramatic holes. Change par, not the golf course.

Great expectations

It’s hard to remember a more anticipated professional debut than Matthew Wolff’s this week at the Travelers Championship. Wolff—along with former Oklahoma State teammate Viktor Hovland, Cal standout Collin Morikawa, and USC stud Justin Suh—represented a stellar crop of new professionals at TPC River Highlands. Their excellence in collegiate and amateur play has led to lofty expectations.

In particular, the degree of hype for Matthew Wolff hasn’t been seen in a while, maybe not since Tiger Woods turned pro in 1996. Pundits have compared Wolff and his contemporaries to some of the game’s current best. I think it’s unfair and too soon to do that. Every great player is unique, and pro golfers usually take time to come into their own. Just look at two of last year’s amateur standouts, Norman Xiong and Braden Thornberry. To date, each has struggled on the Web.com—whoops, Korn Ferry Consulting Tour, ranking 147th and 114th, respectively, on the KFC Points List. So let’s allow Wolff, Hovland, Morikawa, and company to chart their own paths over the next few years.

A risk worth taking?

A less-heralded young gun, and a player who deserves to be mentioned alongside the above group, is former Alabama star Davis Riley, who turned pro in the winter. Foregoing the second semester of your senior year is not a well-traveled path, but given the PGA Tour’s new schedule, it might make sense. Hovland and Wolff will each have a tough time maximizing their seven allowed exemptions before the end of the season, which reduces their chances at earning a PGA Tour card or even a spot in KFC Tour Finals. By turning pro early, Riley has been able to grind it out all season on the Web, err, KFC and has gone from Monday qualifiers to 62nd on the points list.

With six regular season events on the schedule, Riley an outside shot at the top 25, and barring disaster, he will at least have a top-75 points finish and a chance at a PGA Tour card via the Web.com, I mean, KFC Tour Finals. By turning pro early, he has given his talent time to rise to the top. His better-known peers will have to rely on hot play in the next few weeks, or else they will find themselves in KFC Tour Q-School.

Balancing restraint and boldness

June started off with a bang, thanks to the U.S. Women’s Open at Country Club of Charleston. The tournament gave us a look at some of the boldest greens and bunkers ever built by Seth Raynor. These features generate interest on the flat site. If you go across town, you will find another kind of Raynor design, Yeamans Hall. There, he was blessed with much more interesting topography, so he used more restraint. On the flat portions of Yeamans, his bunkering and greens have scale to rival CC of Charleston, but on most holes the features are more subdued, and the topography stars.

-

The 11th fairway at Yeamans Hall with its subtle contours

-

The uphill 12th at Yeamans Hall has a tame green

-

Looking back at the 14th fairway at Yeamans Hall from the green

-

The tremendous 14th hole at Yeamans Hall and its unbelievable terrain

-

The rolling land off of the 15th tee at Yeamans Hall

-

The sand-encircled island green at CC of Charleston

-

The huge lion's mouth green at CC of Charleston

-

The berm on the 15th at CC of Charleston

-

The view from the tee of the bold bunkering the 14th at CC of Charleston

-

The tremendous scale of the false front at CC of Charleston's 11th

-

The false front on the 12th green at CC of Charleston

This is also true when at Raynor’s two designs in Chicago, Chicago Golf Club and Shoreacres. Chicago’s site is akin to Charleston’s, but at Shoreacres there is a fascinating ravine-scape. At the latter, therefore, you will find a restrained Raynor, and at the former, some of his boldest work.

-

The 11th at Shoreacres has amazing natural terrain

-

Raynor's green for the 11th at Shoreacres is subdued because the land is the star

-

The 4th, 5th, and 6th traverse some of Chicago Golf Club's flattest terrain but possess some of the property's boldest greens and bunkering

If you want to see Raynor unchained with bold land and bold features, go to New Haven, Connecticut, and see Yale.

-

The great topography at Yale's 2nd

-

The bold 2nd green

-

The Biarritz 9th at Yale

-

The approach to the 10th at Yale

-

The tremendous 8th green at Yale

-

The 12th Alps hole at Yale

Knowing when to practice restraint and when to go big is perhaps the most difficult skill for an architect to master. Much like championship venue setups, the best designs push to the edge. A hair over, and it will be declared “goofy” or “unfair.” One of the most admirable traits of Seth Raynor and many other Golden Age architects was their sense of where that line was on each site.

by

by