I didn’t grow up playing at places like Los Angeles Country Club, so I discovered classic golf architecture by reading. My first and favorite book on the subject was The World Atlas of Golf, which my dad found in a used bookstore and brought home to me when I was 10 or 11. It had writing by Pat Ward-Thomas and Herbert Warren Wind as well as maps of courses like Pine Valley, Royal Melbourne, Casa de Campo, and Turnberry.

Since the writing intimidated me slightly, I spent a lot of time staring at the maps. I imagined playing each shot. I was struck by how different the courses were from each other—the enormous variety that existed in the world of golf. Soon I asked my parents for a large sketchbook, and I started drawing diagrams of my own imaginary courses.

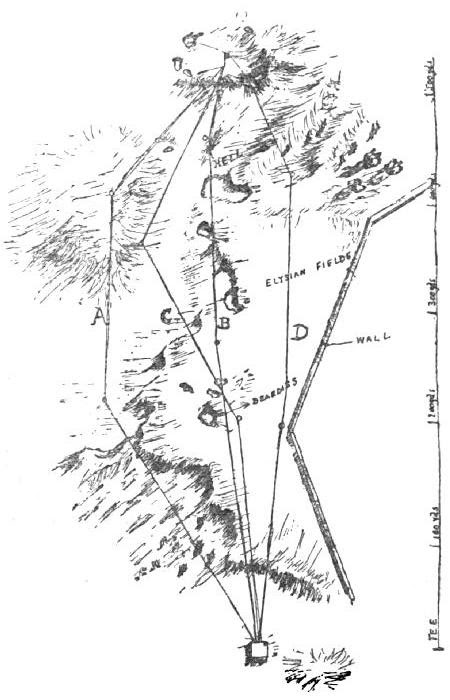

A couple of years later, I read Alister MacKenzie’s Spirit of St. Andrews. Again, the maps fascinated me, especially the one of the par-5 14th hole at St. Andrews. With a series of dotted lines, MacKenzie showed the different routes players could take up the massive, bunker-strewn fairway. How cool was it that four different players could effectively invent four different holes within a single corridor!

Golf didn’t have to be an execution test only, I realized; it could be something like a creative act. The courses I drew became wider and more strategically intricate.

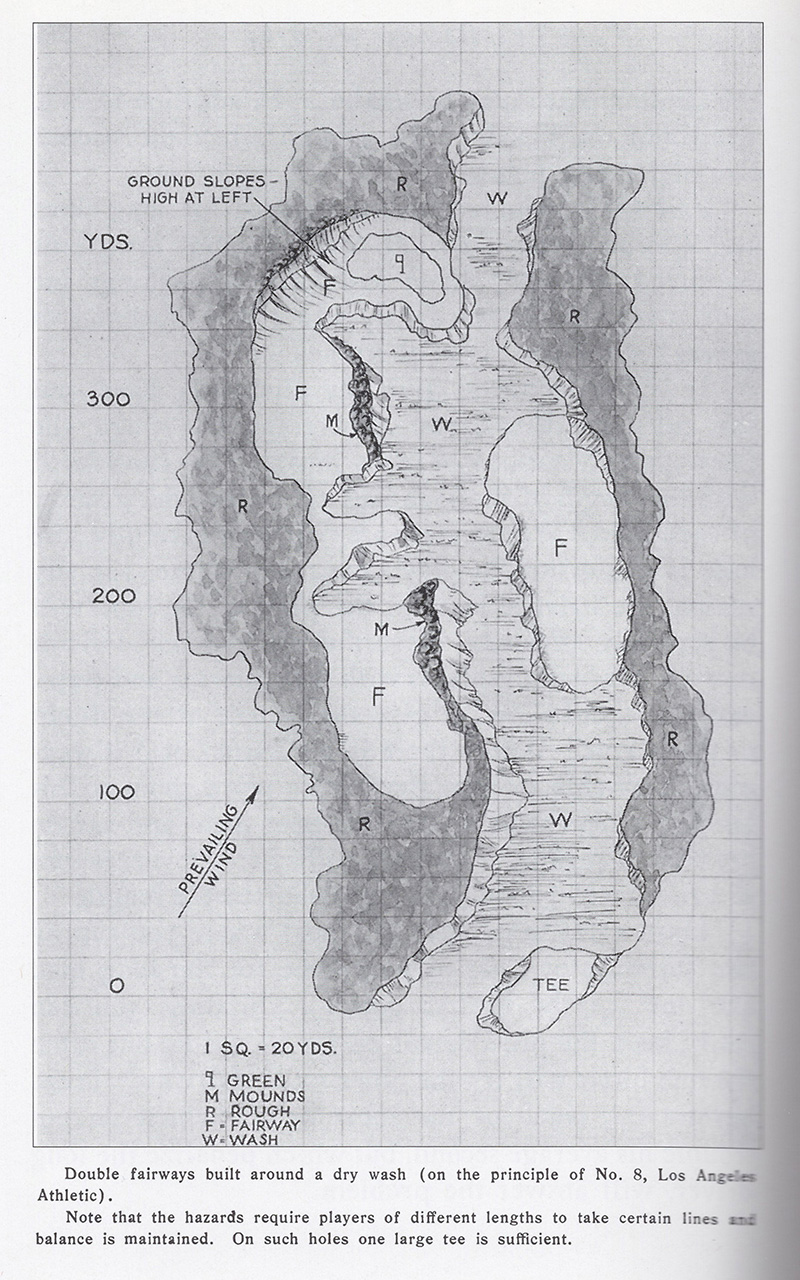

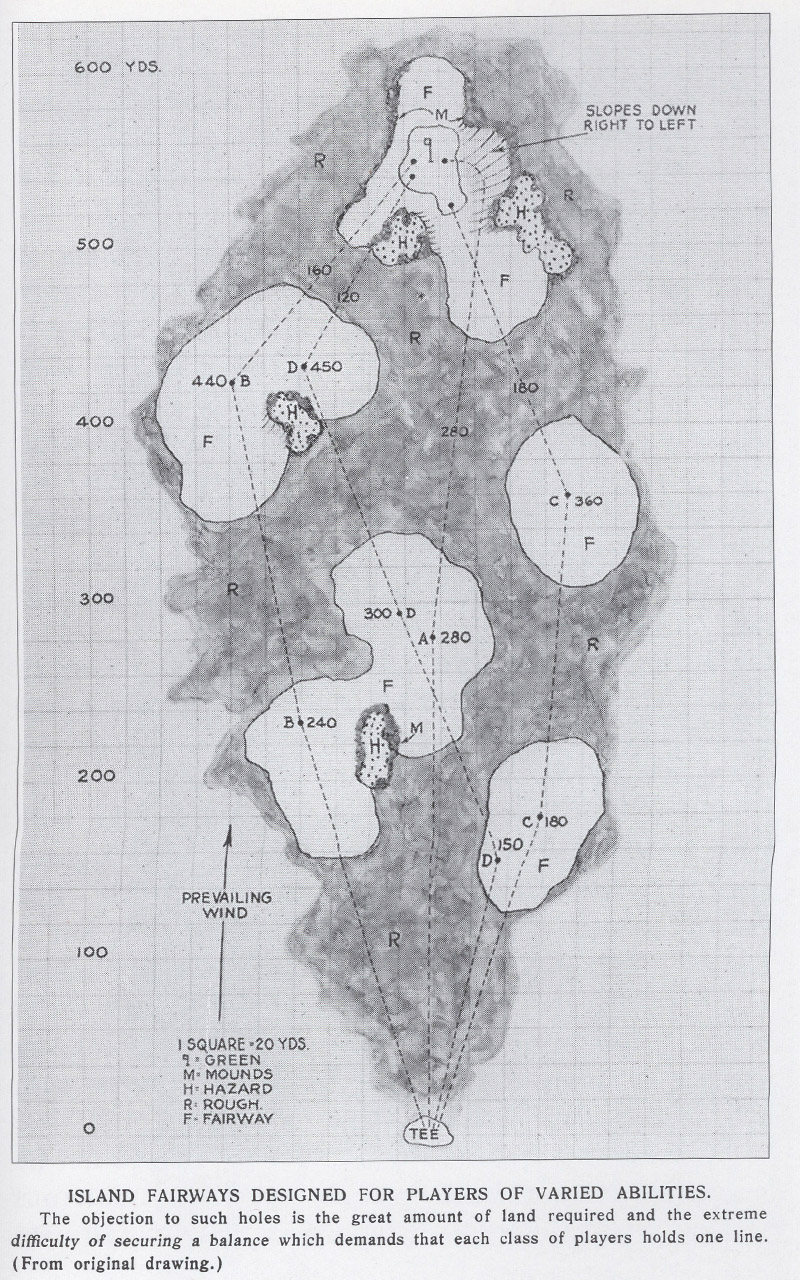

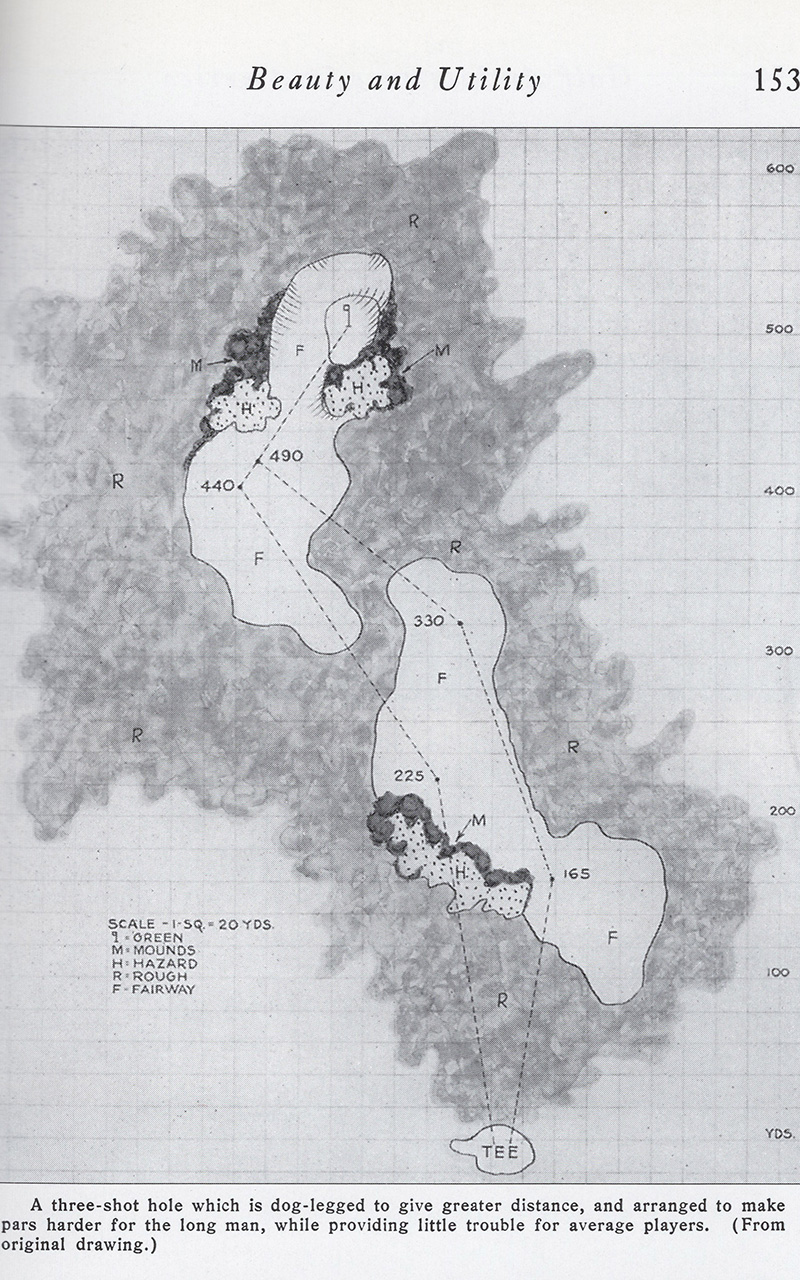

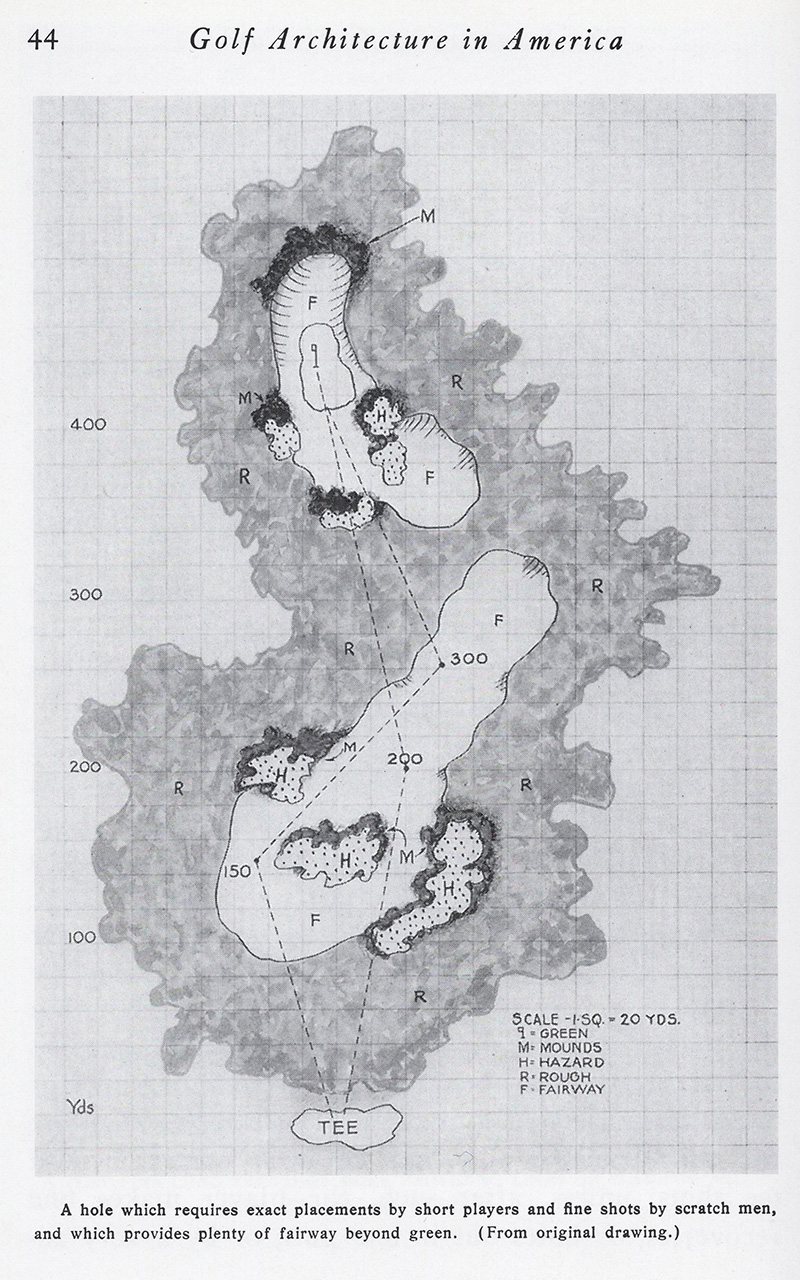

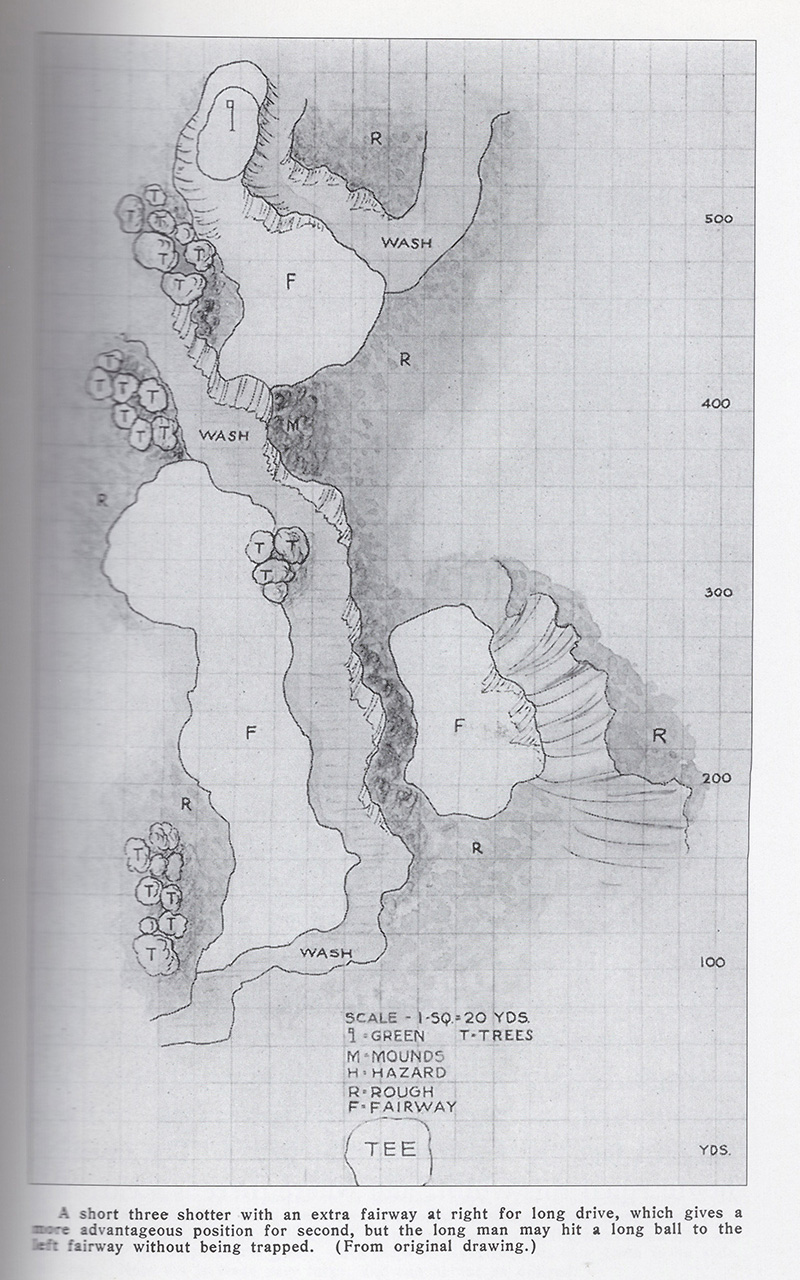

At the time, I hadn’t read or even heard about Golf Architecture in America, the book that LACC architect George Thomas published in 1927. I would have been captivated by Thomas’s hole diagrams, which are bursting with ideas for how to give golfers access to many holes within one.

I love golf course design because, when it’s done with imagination and verve, it can turn golfers into adventurers.

That’s why I was so excited to see the North Course at LACC host the U.S. Open. More than any other American course capable of staging a major championship, it embodies George Thomas’s vision for holes within a hole and courses within a course. On almost every shot, you can choose your own path to success (or failure), depending on your strength, skill level, courage, and golfing personality.

The problem is, the way top professionals play the game today tends to flatten the complexities of old courses.

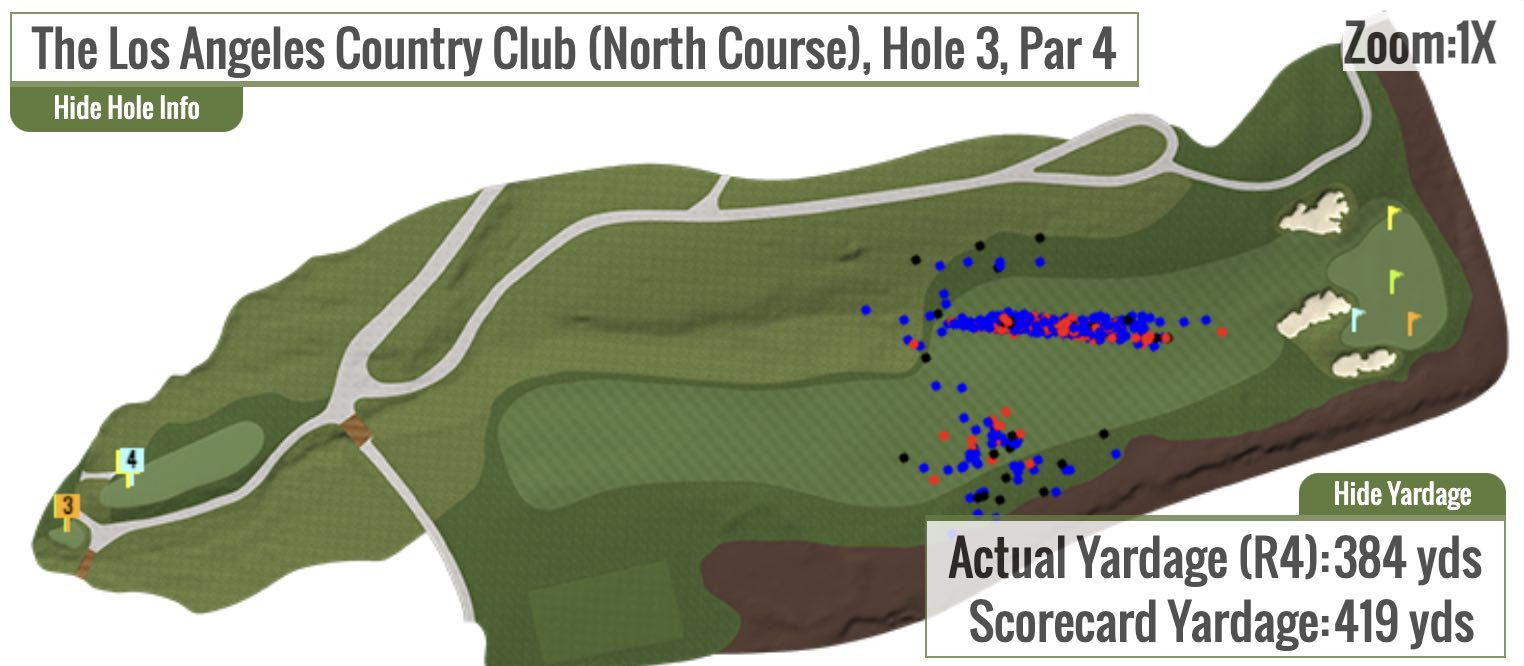

For instance, the third hole at L.A. North is meant to have options off the tee. Strong players can gamble and try to to get past the finger of barranca that takes up the left-center section of the fairway. Tee shots that make a 250-yard uphill carry will funnel to the bottom of a gully, leaving a blind but short approach to the ridge-top green. Shorter hitters can opt for the hill on the right, where they’ll have a good view of the green but a sidehill lie and a long way to go.

This was a heck of a hole in 1928, and it still is today for most amateurs, even though there’s no room to move the tee back. Competitors in the U.S. Open, however, can make the 250-yard uphill carry with ease. Nearly everyone in the field this past week ended up past the hazard and in the (increasingly divot-pocked) gully all four days.

Similar dynamics emerged throughout the course. Modern distance bypassed Thomas’s conservative options, making the aggressive lines appear to be the only ones. The hole that retained largest share of its original complexity, the short-par-4 sixth, thrilled fans and flummoxed players. L.A. North has several other holes as brilliant, but their nuances were overwhelmed by the U.S. Open field.

And that’s okay, maybe inevitable. The 95-year-old course still held its own, yielding only 18 72-hole scores under par and summoning great shots from the world’s greatest players.

(By the way, I didn’t see any mea culpas from those who called L.A. North a pushover after a low-scoring first round. They just shifted to complaining about the lack of on-site buzz and the membership’s apparent efforts to turn a national Open into a private garden party—which, you know, valid. Still, how about some accountability for those Thursday takes? They were bad!)

I’m starting to wonder, however, whether Golden Age golf architecture is good for the U.S. Open, and vice versa.

Throughout this past week, it seemed like the type of golf course design I love was on trial. Every birdie, every stroke of luck was interpreted as an indictment of L.A. North, the USGA’s setup, Gil Hanse’s restoration, George Thomas’s architecture, and the entire philosophy of strategic design. When Wyndham Clark’s wipey tee shot on the 72nd hole landed safely in the fairway, a segment of golf Twitter flipped out. Outlaw width and angles! Exonerate Rees Jones!

Something tells me the reaction would have been different if Rory McIlroy had caught the same break.

Ultimately, though, championships shouldn’t be the main prism through which we see and judge great golf architecture. Wide, intricate courses like George Thomas’s and Alister MacKenzie’s cater primarily to the amateur. Some can serve as championship venues, but that’s not their highest purpose.

So if the consensus is that L.A. North failed to test the pros properly, screw it. Establish a new U.S. Open rota of Torrey Pines, Bellerive, and Hazeltine. Narrow the fairways, grow the rough, and avoid any design characteristics intended to make the game more pleasurable and interesting. It’s just one tournament. Perhaps, over time, some of us will stop paying attention to it. And perhaps then we’ll be able to focus on the actually important task of building, renovating, and restoring courses that are fun for average golfers to play.

by

by