The Greenbrier, the host of this week’s season-opening tournament—sorry, tribute—on the PGA Tour, has a marketable history. During the Civil War, the Confederate and Union armies fought over the property, nearly destroying it. Military forces took over the resort again during World War II and converted it into a hospital. The next decade, at the height of the Cold War, the U.S. government built a nuclear fallout shelter under the resort. Today, “The Bunker” is one of The Greenbrier’s attractions, along with falconry and, of course, golf.

So we hear on the telecast every year. Oddly, we don’t hear as much about the 1979 Ryder Cup, played at the West Virginia resort’s Greenbrier Course.

These days the Greenbrier Course lives in the shadow of its older sibling, the Old White TPC, a restored C. B. Macdonald design that hosts A Military Tribute at the Greenbrier. But the Greenbrier Course has, or had, an impressive architectural pedigree of its own. Seth Raynor built it in 1924 and included several types of holes not found in his other designs. In preparation for the 1979 Ryder Cup, however, Jack Nicklaus redesigned the course. He lengthened it, installed new bunkers and greens, added ponds, and, to quote Tom Doak’s Confidential Guide, “obliterated all trace of its origins.”

The Greenbrier Course today. Photo credit: greenbrier.com

So that’s a sad story. Let’s move on.

A reverse Brexit

Today, the 1979 Ryder Cup is best remembered for the debut of Team Europe. From 1927 to 1977, Team Great Britain and Ireland took home the Cup only three times. None of the matches between 1971 and ’77 were even close, and concern grew that the Ryder Cup would never again be competitive.

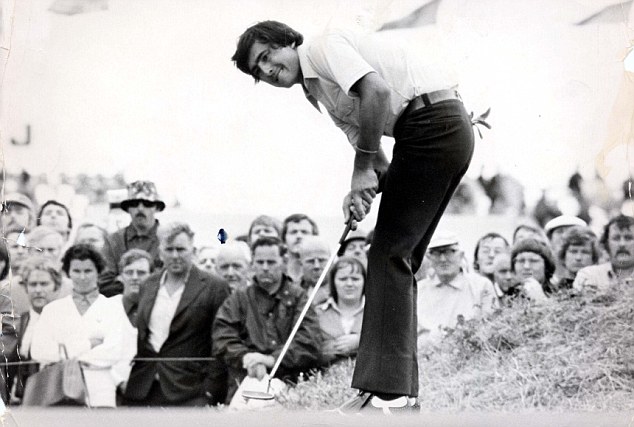

After the 1977 match, Nicklaus wrote to the Earl of Derby, the chairman of the British Ryder Cup committee, saying that if the Ryder Cup wanted “to continue to enjoy its prestige, it was vital to widen the selection procedure by bringing non-British players to the British team.” But Lord Derby had another reason to cast his eyes across the Channel: a young, charismatic Spaniard named Severiano Ballesteros Sota. The year prior, a 19-year-old Seve had become a star by dueling Johnny Miller at Royal Birkdale in the Open Championship.

Seve Ballesteros at the 1976 Open Championship. Photo credit: Daily Mail

When the British Ryder Cup committee announced the launch of Team Europe, Lord Derby admitted that he had Spain on the brain: “It was a natural step to broaden our team selection to include European players and this was undoubtedly helped by recent Spanish successes in winning the World Cup and by the achievements of Severiano Ballesteros.”

With the addition of Ballesteros and his countryman Antonio Garrido to the young talent (Nick Faldo, Sandy Lyle) and veteran leadership (Bernard Gallacher, Tony Jacklin) of the Isles, Europe cut a formidable figure at The Greenbrier. Meanwhile, the American squad seemed weaker than it had in years. Nicklaus had not qualified, and Tom Watson withdrew at the last minute to attend the birth of his first child. That left Team USA to go to battle with eight rookies.

(Sidebar: one of those rookies was Lee Elder, the first African American to play in a Ryder Cup. He also shared a first name with a team member, which led to some awkwardness at the pre-match banquet. Take it away, Dan Jenkins: “[N]on-playing U.S. Captain Billy Casper introduce[d] Lee Trevino… as ‘a credit to his race.’ Casper then introduced a woman named Rose as Trevino’s wife. Now we’re getting somewhere, because Rose is the wife of black golfer and Ryder Cup player Lee Elder. Casper obviously had his Lees crossed up.”)

Team USA at the 1979 Ryder Cup

Spanish bombs

As unfamiliar as the run-up to the 1979 Ryder Cup felt, the result was same old, same old. The Americans jumped out to a three-point lead on Day 1 and dominated singles on Sunday. The final score was 17-11.

The 22-year-old Ballesteros, who would go on to become one of the greatest Ryder Cuppers ever, went 1-4. He and Garrido dropped three matches to the U.S. rookie team of Larry Nelson and Lanny Wadkins, and Seve lost his singles showdown with Nelson 3 & 2. Afterwards, the Spaniard served his comments to the media with a generous helping of salt. About Nelson holing out a wedge on the 9th hole, he said, “He was lucky. From 1,000 balls, he will never hole the 9th again.” (Later, Nelson replied, “I don’t know what’s lucky about that.”) Ballesteros also had some thoughts on the Greenbrier Course’s setup: “I think they put the course exactly for the American team. We always play very slow greens [in Europe]. This is where we got beat… on the greens.” (American Hubert Green’s response: “That’s not true. They putted better than us all week.”)

Clearly, tension was already festering between Seve and the Americans. As Nelson put it, “I think everybody played their best against [Ballesteros] this week because everyone wanted to beat him.” Over the next two decades, this animosity would fuel some of the most exciting Ryder Cups in history.

Team Europe celebrates its 1985 Ryder Cup victory

No brownie points for Brownie

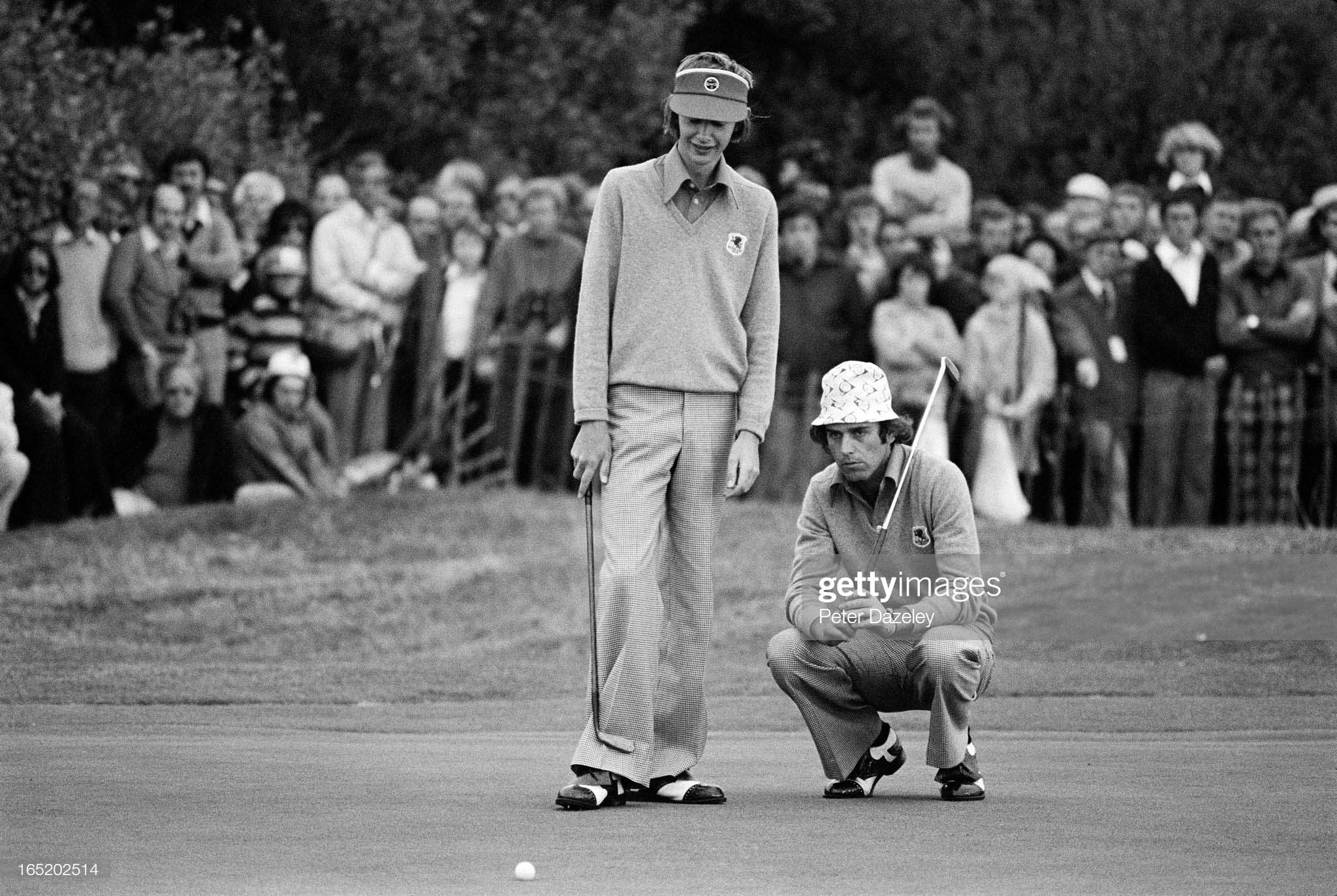

But the big story in the months after the 1979 match involved two other young players: 22-year-old Ken Brown from Scotland and 25-year-old Mark James from England. The pair caused such trouble in the European team room that the British PGA ended up fining both men and banning Brown from international competition for a year. These facts are all the more striking today given the stature of Brown and James in the golf world. Brown is now a commentator for Sky Sports as well as the beloved host of “Brownie Points” on Fox’s U.S. Open coverage, and James served as captain for Team Europe in the 1999 Ryder Cup. Both have established themselves as dignified elder statesmen of the game.

Ken Brown (left) and Mark James (right) at the 1977 Ryder Cup at Royal Lytham and St. Annes (Getty)

At The Greenbrier in 1979, however, Brown and James apparently acted like sullen, rebellious teens. Their first offense: refusing to wear their team uniforms on the way to the event. “They behaved unbelievably stupidly,” said John Jacobs, the European captain in 1979. “From the word ‘go’ when they appeared at the airport dressed as though they were going on a camping holiday, they set out to be as disruptive as possible.”

After arriving in West Virginia, Brown and James skipped a team meeting to go shopping. As the week went on, their small offenses added up. “They didn’t stand to attention for national anthems,” Jacobs added. “They covered their faces at the dinner and wouldn’t have their pictures taken with the team.” Photos do exist of Brown and James standing with the 1979 team, but in all of them James wears a dark frown.

-

Team Europe at the 1979 Ryder Cup

-

Mark James (left) and Ken Brown (right)

On the golf course, neither player exactly redeemed himself. As partners for the Friday morning four-ball, Brown and James lost 3 & 2 to Lee Trevino and Fuzzy Zoeller. James then withdrew from the event, citing a chest injury. That left Brown to torment his new partner, Des Smyth, in afternoon foursomes. Brown refused to speak to Smyth during the match, and the duo lost 7 & 6 to Hale Irwin and Tom Kite. “Ken didn’t talk to anybody,” Jacobs said. “He just hit it and walked up the fairway. I had to apologize to Des in front of the whole team.”

The European veterans were equally unamused by Brown and James’s antics. “They played pranks that my children would never have played,” Tony Jacklin said. “It wasn’t just childishness, it was an effort to disrupt everything. They were just like yobs.”

Why Brown and James acted this way remains a mystery, partly because neither man has told his side of the story in public. Maybe they weren’t happy about traveling all the way to West Virginia to play for free in what they must have regarded as a glorified exhibition. Or maybe they were just young and dumb.

The Brookline skirmishes

Either way, Brown and James’s behavior made a lasting impression. Almost 20 years later, some of their teammates from The Greenbrier still couldn’t wrap their heads around the notion of Mark James as a Ryder Cup captain. Their consternation deepened when he selected Ken Brown as one of his vice captains for Brookline. In 1998, Jacklin told The Independent, “I’m a member at The Greenbrier, where the match was played in 1979, and there isn’t a picture hanging in the clubhouse where [James] looked into a camera lens. He and Ken, for whatever reason, made it their business to sabotage any chances the team had.”

From left to right: Sam Torrance, Mark James, and Ken Brown at the 1999 Ryder Cup (Getty)

James’s team lost in 1999, and his decision to sit three rookies until Sunday singles was questionable at best, but he remained popular among European players. He did end up causing some controversy, though. A year later, he authored a tell-all about the Battle of Brookline, Into the Bear Pit. One passage described James receiving a good-luck message from his 1979 teammate Nick Faldo. Instead of reading it to the team, he tossed it in the trash. Faldo was furious not only that this anecdote had seen the light of day but also that James had kept his position as vice captain for Team Europe in 2001. With Faldo repeatedly airing his displeasure to the press, the European Ryder Cup committee asked James to step down.

Choose your own adventure

Is there anything to learn from this odd, winding vein in golf history? Let’s try three options:

First, the late 70s were the peak of big-time competitive golf, unlikely to be reached again. For a 21st-century golf fan, it’s hard to imagine how many bold, irreverent personalities descended on The Greenbrier in 1979. You had Lee Trevino calling out Ken Brown for slow play by saying, “Why, in the whole round, I only shaved twice!”; you had Mark James looking like a mustachioed variant of Al Pacino in Dog Day Afternoon; and you had Brian Barnes taking full swings with a wooden pipe hanging out of his mouth. In comparison, today’s tour golf seems utterly anodyne.

Second, continental Europe may have saved the Ryder Cup, but not right away. Team Europe lost again in 1981, and again in 1983. When they broke through in 1985 at The Belfry, however, three of their top four point scorers were from the continent: Ballesteros, Manuel Piñero, and Bernhard Langer.

Third, it has been 40 years since the Walloping in West Virginia and 20 years since the Battle of Brookline, so it’s high time for Ken Brown and Mark James to get involved in another Ryder Cup. Come on, Paddy. You still need vice captains for 2020, right?

Flashback Friday is The Fried Egg’s weekly dive into the fascinating, forgotten details of golf history. For an audio rendition of this week’s installment, listen to the Shotgun Start podcast.

by

by