For the past several weeks, golf course architect Keith Cutten has been on the campaign trail for his new book, The Evolution of Golf Course Design. He has become a regular presence on Twitter and Instagram, offering up a steady supply of historical photos, anecdotes, and quotations. He has also been an engaging guest on multiple podcasts. When the first copies of his book arrived in mailboxes in late November, several recipients posted photos of theirs on social media. The prevailing sentiment: Can’t wait.

As a physical object, The Evolution of Golf Course Design does not disappoint. It is large and sturdy, and it has perhaps the best collection of historical golf course photos I have ever seen in one volume. The book would make a beautiful coffee-table centerpiece.

Yet it is not just decoration; Cutten intends it to be a serious contribution to scholarship on golf course design. While he acknowledges that plenty has been written on individual architects, he insists that “precious little (if anything) has been published about the evolution of golf course architecture.” He further claims that although “the ‘what-and-when’ of golf course architecture has been well documented, the ‘how-and-why’ has lagged.”

So with The Evolution of Golf Design, Cutten seeks not only to weave together the biographical threads of the most influential golf architects of the past two centuries, but also to explain how broader economic, social, and cultural trends shaped their work. The scale and ambition of this project cannot be overstated.

The book is split into two sections. The first is a decade-by-decade survey of the history of golf course design, starting in the 1830s and finishing in the 2010s. The second is a compendium of profiles on architects from Old Tom Morris to Gil Hanse, authors from John Low to Geoff Shackelford, and “visionaries” from Henry Fownes to Mike Keiser. Between the two is a chapter on women associated with golf architecture, a welcome addition to what is usually a single-gender story.

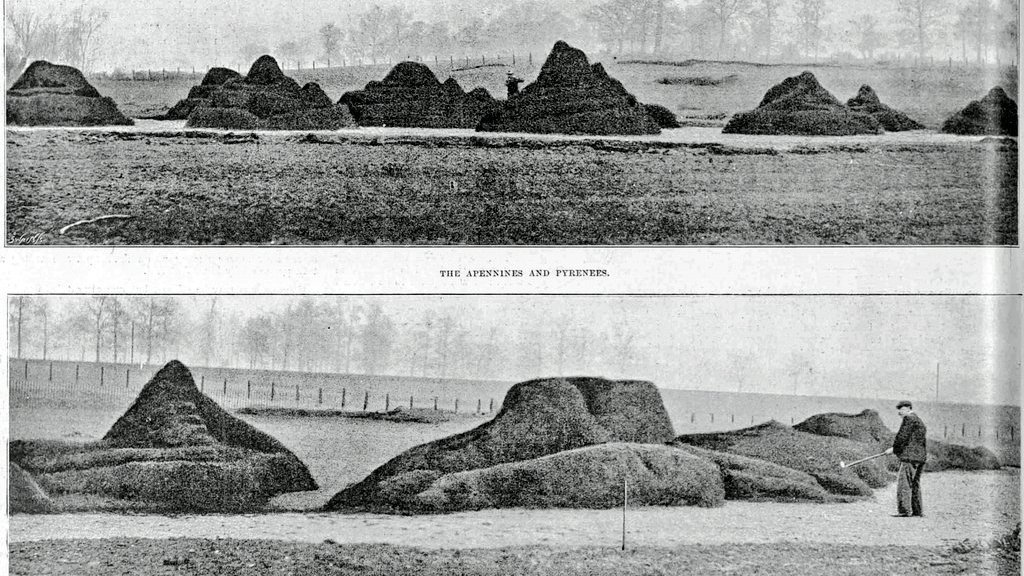

-

Bizarre Victorian shaping at Tom Dunn’s Hanger Hill in 1901. Research credit: Simon Haines @hainesy76

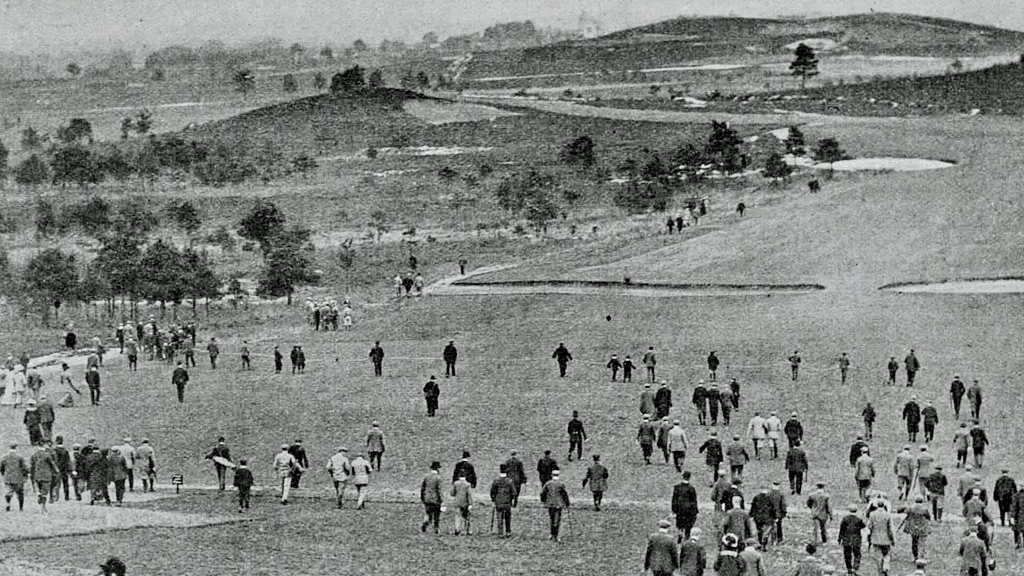

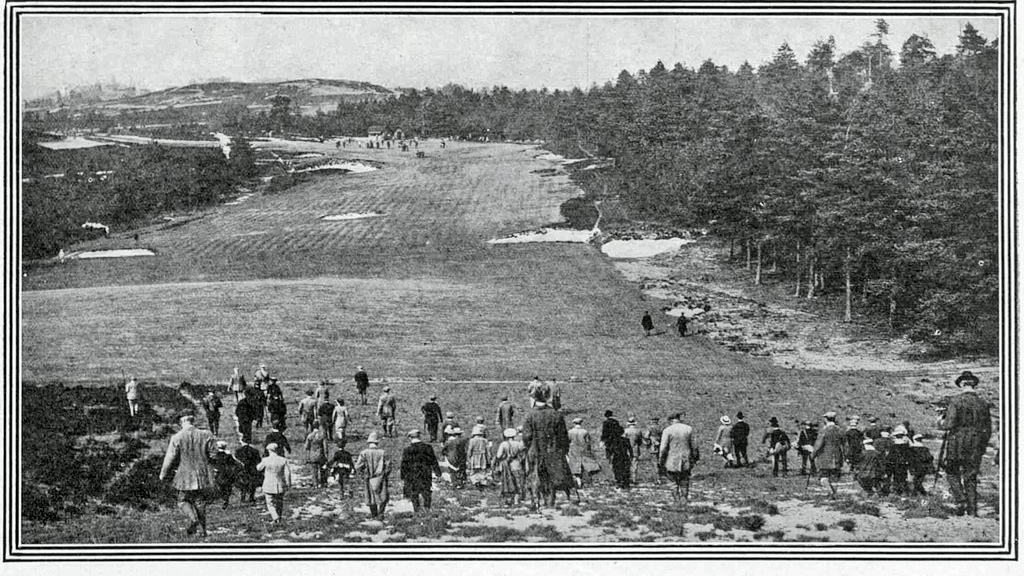

-

The 10th hole at Willie Park Jr.’s Sunningdale in 1902. Note the penal, Victorian-style cross bunkers. Research credit: Simon Haines @hainesy76

-

The 10th hole at Sunningdale in 1914, after Harry Colt injected naturalist aesthetics and strategic design into the course. Research credit: Simon Haines @hainesy76

-

The 18th hole at Alister MacKenzie’s Pasatiempo soon after the course opened in 1929.

-

The 3rd hole at George Crump’s Pine Valley in 1936. Research credit: Simon Haines @hainesy76

-

The return of the cross hazard: the 3rd hole at Robert Trent Jones’s Ponte Vedra in 1953. Courtesy of the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District and Michigan State University Turfgrass Information Center

-

Pete Dye's TPC Sawgrass design as it wraps up construction in 1980. Credit: PGA Tour

-

The wholly manufactured 17th hole at Shadow Creek, a 1990 Tom Fazio design. Photo credit: Jon Cavalier @linksgems

-

The 5th hole at Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw’s Bandon Trails, which opened in 2005. Photo credit: Garrett Ford

As Cutten acknowledges, a collection of golf architect biographies is hardly new. Ron Whitten and Geoffrey Cornish used that approach in their landmark volumes The Golf Course and The Architects of Golf. The major innovation of Cutten’s book, therefore, is the first section.

With this decade-by-decade narrative, he attempts nothing less than to move an entire discipline forward. Most books and articles on the history of golf architecture have subscribed, consciously or not, to “great man theory”—that is, the notion that the past can be understood as a series of contributions made by exceptional (usually male) individuals. With the first section of The Evolution of Golf Course Design, Cutten tries to break free of that framework and to examine the larger social world in which golf course architects plied their trade.

He does so with particular intensity in his chapters on the turn of the 20th century. Inspired by Thomas MacWood’s Golf Club Atlas series “Arts and Crafts Golf,” Cutten shows that the transition from Victorian to heathland golf architecture in England was both a product of and a reaction to industrialization.

Geometric, repetitive, and blatantly artificial, Victorian golf design took its cues from the landscaping and gardening of the period. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, however, two sea changes occurred: 1) improvements to rail travel made it easier for English golfers to familiarize themselves with Scottish courses, and 2) the Arts and Crafts movement, which championed handmade goods, emerged in response to machine-assisted mass production.

Inspired by the naturalism of the Scottish links and by the rustic aesthetics of Arts and Crafts, a new breed of golf visionary—Horace Hutchinson, John Low, Willie Park, Jr., and Harry Colt, among others—began building strategic, tastefully contoured courses in the English heathlands. Cutten demonstrates that these courses, the first inland designs to rival the seaside links in interest and beauty, came into being not just because a few individuals had the genius to create them, but because those individuals absorbed and applied the influences of their era.

Later in his narrative, Cutten points out that similar dynamics may be at work today. In opposition to globalization, a taste for local and artisanal products has become fashionable. (Think craft beer, Etsy, the TV show Making It, etc.) This millennial revival of Arts and Crafts may help explain the growing popularity of the design-build model of golf architecture, as practiced by Pete Dye, Bill Coore, Tom Doak, and Gil Hanse.

These kinds of ideas further our understanding of where golf course design has been and where it might go. However, while Cutten outlines several such theories, he does not truly prove them. For instance, his discussion of the Victorian golf architecture would have benefited from more information about, or even just photos of, the man-made landscapes of the period. Similarly, his chapters on the 1890s and 1900s could have given more detail about what the aesthetic principles of Arts and Crafts were and how they appeared in the designs of heathland courses.

Given the scope of The Evolution of Golf Course Design, it would be unfair to expect depth on every topic. Nevertheless, Cutten’s research methods may have prevented him from addressing the how-and-why of golf architecture history as thoroughly as he intended. As he said on the iSeekGolf podcast, his research focused on two tasks: writing profiles of major architects and constructing a timeline of historical events. To assemble his decade-by-decade survey, he stitched together those bodies of evidence.

The seams occasionally show. Most chapters in the first section of the book begin with historical background and proceed through summaries of the achievements of individual architects. This approach sometimes works against Cutten’s intentions: it emphasizes the what-and-when rather than the how-and-why, and it retains a trace of the old “great man theory” of golf architecture. Perhaps if Cutten had sacrificed some coverage of who built which courses when, he would have been able to dig deeper into why certain design trends evolved.

That said, The Evolution of Golf Course Design is still a milestone and a cause for celebration. The breadth and rigor of Cutten’s factual research, as well as his insight that golf architecture is not sealed off from the surrounding world, make this book an essential addition to any serious golf library.

by

by