“The model public playground”

When the city of Washington D.C. got into the golf business, they did it with the intention of serving as a model for the rest of the country. The goal was to create a template that cities across America could follow in managing their public open space. It all started with East Potomac Park, a portion of the capital’s National Mall. City planners set out to intertwine golf with other outdoor activities to create the ideal public recreation area. The first golf golf course, East Potomac G.C., thrived and prompted the development of more public golf in the city, some of which still exists today – Rock Creek GC and Langston GC. Each course was built with a high design standard and meant to provide affordable golf for all citizens. These facilities were considered by many to be as good, if not better, than the city’s high profile country clubs.

Like many older municipals in America, D.C.’s historic courses have deteriorated through years of heavy use. The National Park Service, which owns the courses, has historically outsourced management of the properties on a short-term basis. That short term focus has deterred management companies from making large capital investments in the courses. NPS is taking a different direction beginning in 2019 in announcing their intention to select a new manager for a long-term lease. This move will allow for major capital improvement and creates a monumental opportunity for public golf.

A brief history on Washington DC

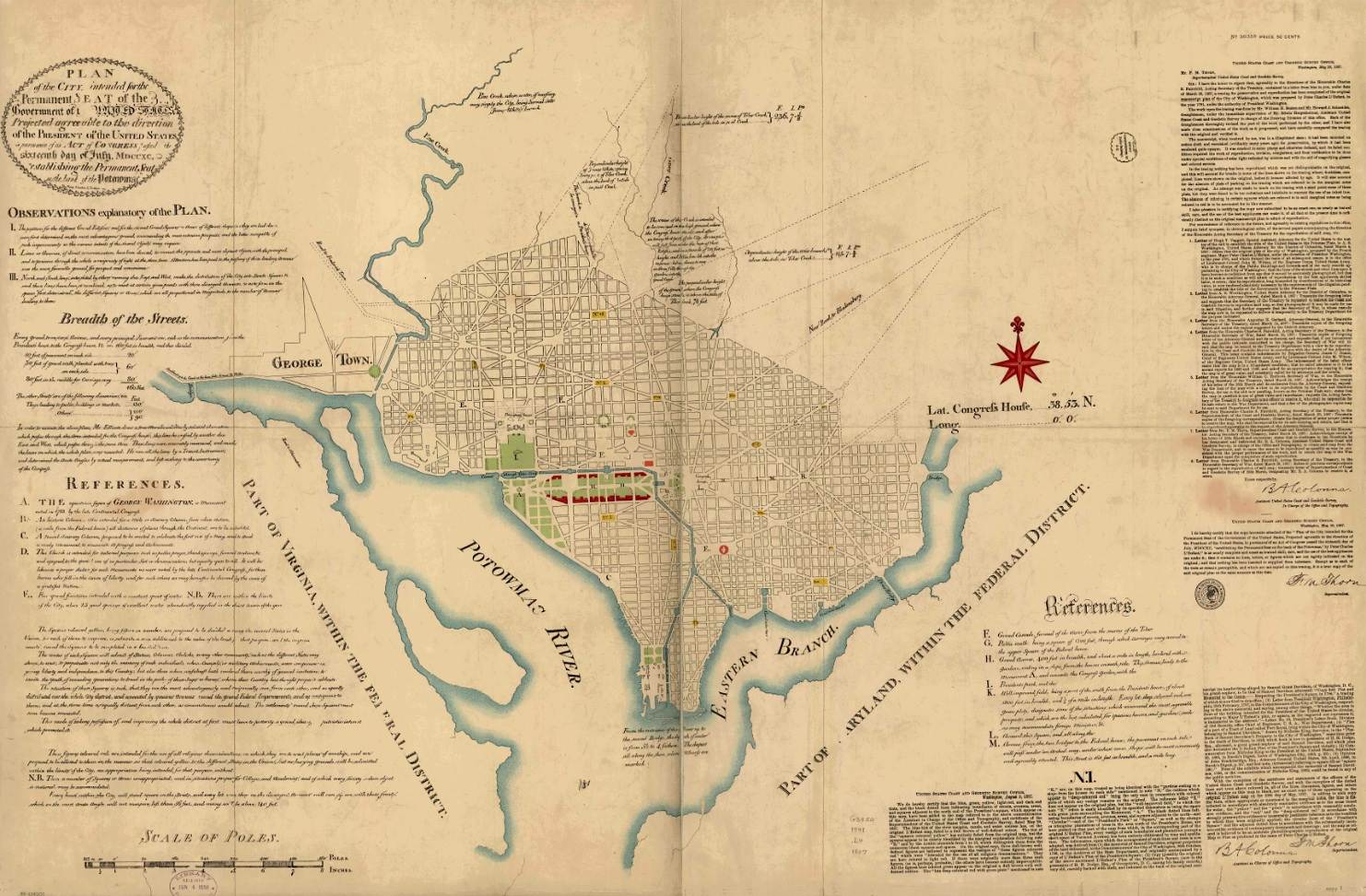

Our nation’s capital boasts one of the world’s most unique and forward thinking designs. Since its inception in 1790, DC’s urban planning and architecture has set a standard for the rest of the country. George Washington appointed noted architect Charles L’Enfant to survey and lay out the city. L’Enfant’s vision was grand and much more intricate than an earlier plan put together by Thomas Jefferson. The centerpiece to the grand plan was the National Mall. According to L’Enfante expert Scott Berg, “The entire city was built around the idea that every citizen was equally important.” It was what made the plan special and differentiated the newly born Washington D.C. from European cities.

The 1791 L'Enfante Plan Credit: National Mall Coalition

In the end, the execution stalled due to concern over funding, and L’Enfante’s refusal to budge. The half-completed masterplan sat for over a century until the MacMillan Commission formed in 1901. The Senate appointed different architects and planners who used L’Enfante’s work as an inspiration. The initiative was the first major implementation of the City Beautiful movement in the United States.

At this time, golf’s popularity was beginning to boom. America’s first municipal courses such as New York’s Van Cortlandt Park, Boston’s William J. Devine and Chicago’s Jackson Park were exposing the masses to the game. These munis became quickly overrun with golfers and led to the flurry of new development to respond to the demand. Courses of this early period were rudimentary, as was typical during the 1890s and early 1900s. When C.B. Macdonald returned from the British Isles and built National Golf Links of America in 1911, golf course architecture stepped up to a new level. NGLA ushered in the Golden Age and a spread of new design philosophies. Unfortunately though, it took some time for high quality Golden Age design to make its way from private clubs to publicly accessible courses. Municipal golf’s growth continued, but the designs remained rudimentary.

The McMillan commission set their sights on the development of West Potomac Park in the early 1900s. This area became home to the Lincoln Memorial and Reflecting Pool, the Jefferson Memorial, and ultimately the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. As a complement to West Potomac, the Commission took on another lofty task, to create “the model public playground” at East Potomac Park. The 1916 plan for this facility would include tennis, swimming, baseball and golf. The latter was a part of the initial rollout of the park.

The aspiration for East Potomac Golf Course was simple yet bold – to build the finest municipal golf facility in the country. Outside of the recently completed Cobbs Creek in Philadelphia, almost every municipal course featured a simple design. For the project renowned architect Walter Travis was hired to lay out the course. Due to the property’s land features and shape, Travis drew inspiration from St. Andrews Old Course and built a reversible 9 hole design. Travis’ design views were portrayed in a 1919 Washington Post article, “In laying out the course, every effort was made to obtain a natural effect rather than the formal construction seen in so many club links. Winding hazards conforming to the general topography of the field have been built and sand traps, carefully located, will be added this spring”

A 1922 photo of East Potomac's original 9 holes Credit: Library of Congress Online Collection

The course opened in 1920 and was an immediate hit, logging 65,345 rounds in its first full year of operation, 1921. The design received rave reviews and even lured President Harding away from games at his country club, Chevy Chase.

The immediate popularity led to the development of the second reversible nine shortly after in 1923. With the opening of the second nine, East Potomac G.C. hosted the 2nd edition of the U.S. Public Links Championship.

Still unable to keep up with the popularity of golf, nine more holes were added in 1925, this time designed by the great William Flynn. Flynn continued the reversible trend and in 1927, the now 27-hole facility logged over 155,000 9-hole rounds. East Potomac certainly achieved its intended purpose as the brilliant design welcomed a wealth of new golfers to the sport in a beautiful setting. The success of the facility inspired Washington D.C. to continue to invest in golf, as did other cities around the country. Municipal golf was no longer a bland afterthought with city leaders often turning to the country’s finest architects for new designs.

An aerial shot of the William Flynn designed 9 holes at East Potomac in 1927. Credit: The National Archives

Shortly after East Potomac, New York commenced work with A.W. Tillinghast on Bethpage State Park, George Thomas designed LA’s Wilson GC, San Francisco entrusted Alister MacKenzie with the building of Sharp Park, and Donald Ross built George Wright in Boston, to name a few. The Golden Age of design had stretched beyond the country clubs and into the municipals.

In with Flynn

Washington D.C. wasn’t done with golf development. Shortly after the completion of the third nine at East Potomac, William Flynn was once again tapped, this time for the redesign and expansion of nine hole facility at Rock Creek GC. The original course laid out in 1907 was set in the city center adjacent to famed Rock Creek Park. Rock Creek’s rolling hills were a stark contrast to East Potomac’s flat property and provided an ideal canvas for Flynn. Known as the Nature Faker, Flynn excelled at using the natural features of the land to serve as the primary hazard. With little in the way of bunkers and water, Rock Creek was another fine example of a course that was exceptionally playable for the beginner. It opened for play in 1926 and gave Washington D.C. two of the premier municipal golf facilities in the country.

The amazing rolling topography at Rock Creek. Credit: Michael McCartin

A place for everyone

Golf became a game for everyone in Washington D.C. During a time of rampant segregation, the city was a leader in the growth of golf within the African American community. The cities first course was built in 1924 and was built on a tiny plot of land adjacent to the Lincoln Memorial. The course was too popular for the meager space and everyone agreed there needed to be a bigger facility. Despite the unanimous agreement, it took until 1933 when Anacostia Golf Course opened near East Potomac. The opening coincided with the Department of the Interior taking control of the operation of the golf courses and formally desegregating them. While the law changed, the East Potomac and Rock Creek courses remained informally segregated until 1953. Anacostia thrived and couldn’t meet the massive demand for the game which led to the building of Langston G.C. The original 9-hole course was designed by North Carolina landscape architect Earle Sumner Draper in 1939. At the time of its opening, Langston was one of only 20 golf courses that welcomed African Americans. Despite notoriously poor conditioning, Langston was a hit because it became a place for the community. It’s inclusivity made the game approachable for all.

Today, each of these courses is a far cry from the high standard they originally set. The current facilities don’t fit with the capital city’s tradition of historical preservation as well as the MacMillan Commission’s visionary intent. With the NPS in the RFI process for a new management company, there is now an ideal opportunity to return them to their original glory.

When D.C. set out with the ambitious goal of creating the ideal public facility, American golf design was in the Golden Age. East Potomac was among the first premier municipal facilities that inspired the development of more across the country. Today, golf design is said to be in a “second golden age”. But as was the case at the beginning of the first Golden Age, most of the design projects are taking place at the country’s private and resort facilities. This presents another opportunity for Washington D.C. to lead by example on a municipal golf resurgence.

If you missed part one, check it out here. If you are interested in voicing your opinion on the Washington D.C. public courses, email the National Parks Service here.

by

by