Welcome to Part 4 of the School of Golf Architecture. For an introduction to this series, jump over to the first installment.

The latest SOGA podcast, featuring a conversation with Andy Staples about collaboration on construction projects, is embedded below. Give it a listen, or keep reading—or both!

Opening thoughts

When talking about how golf courses get built, we tend to focus on the lead architect. We lionize figures like Harry Colt, Seth Raynor, Donald Ross, and Pete Dye; and we see their best-known projects as essentially theirs: MacKenzie’s Cypress Point, Doak’s Pacific Dunes. On the flip side, when a course doesn’t turn out well, we know where to assign the blame.

But the truth is that creating a golf course is a massive collaborative endeavor. First, there are the owners. These may include a developer, a general manager, a green-committee chair, or all of the above. Usually a superintendent will be involved as well. The owners may initiate the project, and their vision may animate it, but their role is often behind the scenes and not very well understood.

Then there are the builders. Among them are skilled shapers who travel the world with architects like Bill Coore, Tom Doak, and Gil Hanse, laboring over bunker edges and green contours. Many of these artisans have followings—and burgeoning design careers—of their own. Less celebrated are the construction companies that do the dirty work of grading, drainage, irrigation, and grassing. Some design firms use these contractors for more specialized shaping tasks; others make a point of not doing so.

In the middle of everything is the architect, appeasing the owners and managing the builders while making sure that the course doesn’t feel like it was designed by committee, even if it was.

So to be a good golf architect, you have to be a good collaborator.

Since I didn’t know much about collaboration in golf course construction, I called up Andy Staples. Andy is uniquely thoughtful about the practical side of the business. He has done excellent work at courses as different as Sand Hollow Resort, Meadowbrook Country Club, and Rockwind Community Links. Right now, he is working on a master plan for Olympia Fields Country Club outside Chicago.

In talking to Andy, I discovered how broad a topic collaboration in golf course design is. We discussed how he works with owners, contractors, and shapers; what “design-build” means and how people misunderstand it; and whether, ultimately, architects get too much credit.

-

The construction of the 12th hole at Sand Hollow. Photo credit: Andy Staples

-

The construction of the 12th hole at Sand Hollow. Photo credit: Andy Staples

-

The construction of the 12th hole at Sand Hollow. Photo credit: Andy Staples

-

The construction of the 12th hole at Sand Hollow. Photo credit: Andy Staples

-

The construction of the 12th hole at Sand Hollow. Photo credit: Andy Staples

-

The construction of the 12th hole at Sand Hollow. Photo credit: Andy Staples

-

The construction of the 12th hole at Sand Hollow. Photo credit: Andy Staples

Edited highlights from the interview with Andy Staples

On the expansion and contraction of the golf course construction industry

Construction technology and the construction industry really started to explode with things like USGA greens and irrigation systems. Coming out of the 50s and 60s, golf got really complicated, and now it wasn’t just pushing up greens, and it wasn’t just doing the rudimentary things you were doing before. So when the golf boom happened, not only were there a lot of projects, there were a lot of complexities that we had to worry about. Who was actually installing these features? Like a USGA green was new for a lot of years. Irrigation systems—you wanted to have somebody who understood how to do those things.

So now with the contraction of the industry, we’ve had a chance to just sit back and breathe and say, okay, there are fewer projects now. I get to spend the time in the field, on the job, to craft the project. I would say now there’s definitely a greater appreciation for spending more time in the field and finding the guys you want on projects. And I think you’re seeing a lot more of that now just because the numbers of the jobs are so much lower.

On what design-build really means

This certainly is a hot topic, and there are a lot of misnomers and assumptions. I think we’ve boiled it down to, is the designer actually on the bulldozer building everything? But to me, design-build means that an owner is just open to not knowing answers to all of the questions. They have a general budget. They have a general timeline. But you’ve got a group of guys, and you begin, and we all participate in the construction, and we work for as long as we need to, and we’re done. And we make adjustments along the way. We’re not focused on absolutely having everything done at a certain time. It doesn’t have to be seeded or open by a certain time. To me, the truest sense of the design-build is just not having those constraints.

In the construction industry, there’s this idea of a cheap, fast, and good. You can do cheap and fast, but it’s generally not good. If it’s good and fast, it’s not going to be cheap. You can have two of those three. But our industry has done a really good job of trying to do all three.

I talked earlier about the fact that construction technology advanced so quickly. These contractors were there to use it—and they could do it for a reasonable number, and they could do it quickly. Architecturally, it probably was not very good, but at least it was structurally sound. Design-build eliminates all of that. We realized that the creative aspects were meant to be an art form. Golf architecture is an art form, not a schedule and not a budget.

That’s where the truest sense of design-build comes in. I consider myself as much of a design-builder as anybody. I’m not always on the equipment; I try not to do that because other guys are better than me. But I have a team of guys I like to work with, and they understand what I’m trying to do. Almost always a contractor is a part of my process because they’re the ones positioned to do the heavy lifting. But I always let the creative aspects take on this design-build mentality.

On working with big contractors and less-experienced shapers

If you’ve got something started and it’s just not going the right direction, the only way to do it is to actually get on the equipment and do it yourself, or just stand there and wait for them to get it right. And I think that’s where this new mentality, this opportunity to spend more time, really is important.

A good site visit is anywhere from two to three days. There are certain parts of the process where you don’t need to be there all the time. But when we’re into the detail work of bunker-edging and green slopes, I’m there the entire day, finishing it off, hand-raking, shoveling, and showing them exactly what we’re talking about. Pictures are very handy. I’ll take a picture or sketch something out on my iPad and say, “Hey, this is what I’m thinking.”

One of the other misnomers is that all golf course contractors need a plan to go off of. I mean, you need to have something that a contractor can bid on, but once you’re building, you can ad lib very quickly. As long as you give them direction and you’re there, you can say, “Yeah, don’t put it over there, slide it over here.” Those are the types of things that happen all the time for me.

On the adjustments made by today’s golf course construction companies

Garrett: Do you think contractors have adjusted to a smaller industry in the same way that architects have? Are contractors starting to operate more along an each-project-is-unique model?

Andy: The industry is segmented. There are companies that get the architecture and understand that architecture matters, that these old clubs matter. Those companies have aligned themselves with the top architects and the top clubs. They set the schedule to do what the architect and the club need, and they celebrate the architecture, celebrate the quality. And they get paid to do that.

Post-recession, a lot of contractors have gone by the wayside, and the bigger contractors have gotten bigger. And now those guys are about the numbers game. The margins are a lot smaller, which means they have to do more jobs. So the schedule is more important to them. They just say, “Don’t keep us here any longer. Don’t make me rent more hotels. Don’t make me rent this equipment. I want to be out of here by this date, period.”

Garrett: So they’re focused on the “fast” part of the “cheap, fast, and good” trifecta at the moment.

Andy: Absolutely.

-

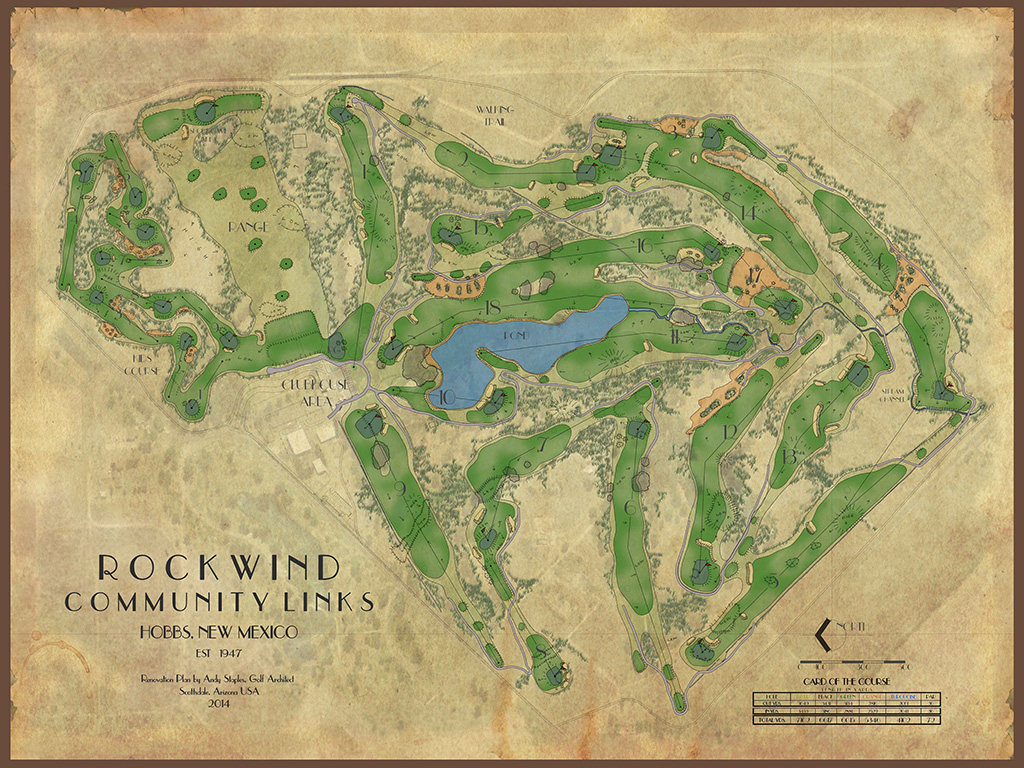

Rockwind Community Links in 2009—or, as it was then known, Ocotillo Park Golf Course—before Andy Staples's renovation (Google Earth)

-

Andy Staples's rendering of his Rockwind renovation

-

Rockwind in 2016, after Andy Staples's renovation (Google Earth)

-

Meadowbrook Country Club in 2010, before Andy Staples's renovation (Google Earth)

-

Andy Staples's rendering of his Meadowbrook renovation

-

Meadowbrook in 2017, after Andy Staples's renovation

On the family atmosphere of a good golf course project

Andy: When you get out on a really good project, you realize that all these guys are having fun. They’re living together or they’re very close together. There are barbecues every Friday afternoon. You just get a sense that it’s a family. And to me that’s what makes great projects.

Garrett: So you think the community vibe of a project shows itself in the work?

Andy: Without a doubt. Without a doubt

Garrett: How do you see that coming through? Do you think people just care more about what they’re doing?

Andy: There’s definitely a certain expectation or personal pressure to perform with design-shapers and people who understand the game of golf. They realize, “You know what, this means something. I want this golf course to be right next to some of the greatest golf courses in history.”

A typical workday starts at 7, and you’re off by 4:30 or 5. Some of the best times I’ve had have been creating those details right at sunset, when everyone’s gone, and we’re out there just as the shadows are lengthening. We go back to a tee and say, “Okay, it’s not quite right.” And we go back and forth. So that kind of buy-in and that kind of passion around creation, I have no doubt only happens when people understand the pressure to perform. And maybe they want to be there. They have no other place to go.

Garrett: They’re like, “It’s better than watching TV in my hotel room. I like being around these people and this place. I think I’ll stay.”

Andy: Yeah. So the rental companies have a 50-hour limit generally on your rental equipment. The best thing is when we’re blowing through the 50 hours a week on running the dozer or running the Sand Pro or running the excavator. Because that means you’re either behind schedule or you’re just building great stuff. You’ve got nothing else to do.

Garrett: Is that your favorite thing to do as an architect?

Andy: There is nothing better than watching things happen in the dirt. Actually I’ll take that one step further. There’s nothing better than seeing things come together not only as you planned it but also with the happy mistakes that only happen in the field. I can’t imagine doing anything else.

On who gets credit for good projects and blame for poor ones

Andy: I still have yet to have any project that I’m proud of where somebody hasn’t had as much or more of a role in its creation than I did. And I think we hear a lot of that from a lot of the other architects. They know that their golf courses wouldn’t be what they are without collaboration from other people.

But you have to boil it down. You can’t say that it was designed by five people. The marketing, the media—people just don’t have the bandwidth for that. They want to assign it to one person. And I think there’s some positive to that. Obviously if you’re the one person, there’s a positive. But there’s no doubt that’s unfair to everybody else.

Garrett: I like to make analogies between writers and architects, but the fun thing that you have as a writer is that you’re completely in control. You’re not really working with anybody else, unless you’re working with an editor or publisher. I know that when something doesn’t turn out right, it’s just my fault. And if it’s good, nobody’s going to come in and alter it. But golf architecture is such a different version of artistry. It reminds me in some ways of filmmaking. We pretend that the director controls everything, and of course they do an enormous amount to shape the identity and the meaning of the film. But you have the actors, you have the cinematographers, you have the editors, you have these other people who have input. And they might do some stuff that you don’t like.

Andy: It brings up a perfect question: what happens if something went wrong? What happens if an owner didn’t want to pay for something, or a contractor short-changed something and we didn’t catch it? Should that be part of the conversation about the quality of the golf course? Should I explain to you, as a golfer or as a rater, “Oh, well, you didn’t realize that we had the wetland here and then there was a storm drain…”? No, you as a golfer, you don’t care about that. So I need to make sure it’s still a good golf course. If it can’t be a good golf course, I’ve got to figure out how not to be involved with it. Or if I am going to be involved with it, it better be good.

Garrett: This is often something that architects bring up as a subject matter that golfers—and especially golf course critics—don’t understand. “You don’t understand what my client asked me to do here. My client asked me to prepare this course for the U.S Open, so I went ahead and prepared the course for the U.S. Open. Why are you critiquing my work if that was the objective of the work?” And that makes sense. If you’re going to criticize a course, you should know what went into its creation. At the same time, you play the course and you have your reaction to it. What is the point of putting effort into the design of a golf course if not to create a good experience for the golfer?

Andy: And make an experience that somebody wants to come back and have again and again and again. So yeah, I’ve heard those excuses. In some respects, I’ve been a part of some of those excuses. I understand it. But I hope to never make those mistakes again. It’s just an excuse for putting out average or below-average work. And that’s one of the things happening now with the reduction of large new-build projects. Those misses are going to become less and less.

-

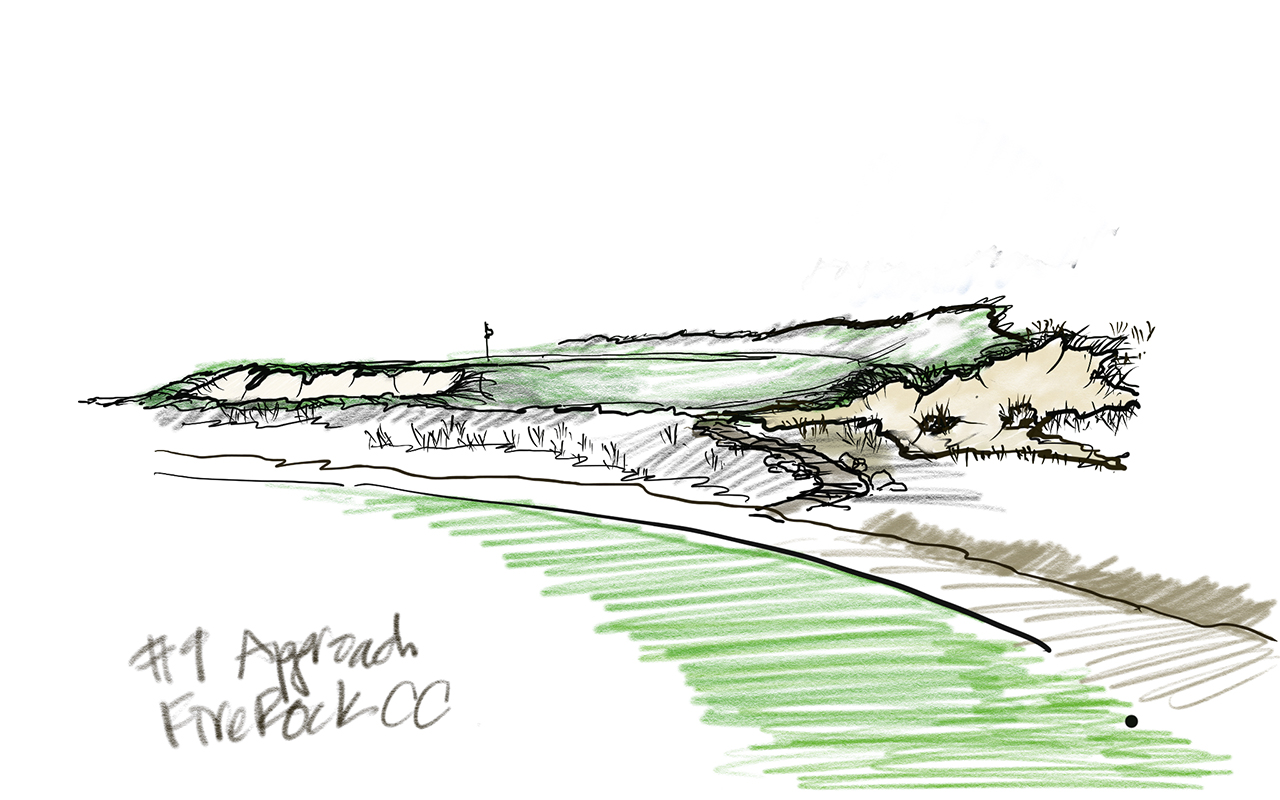

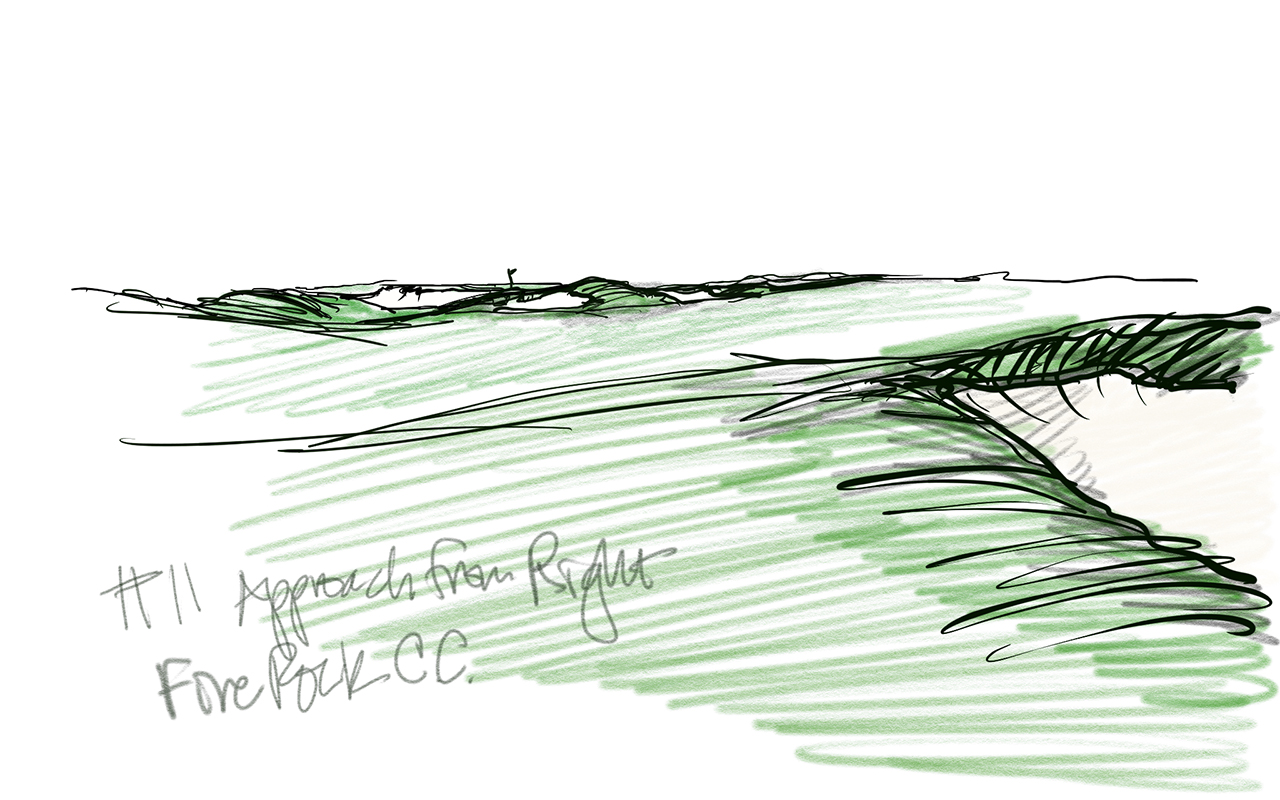

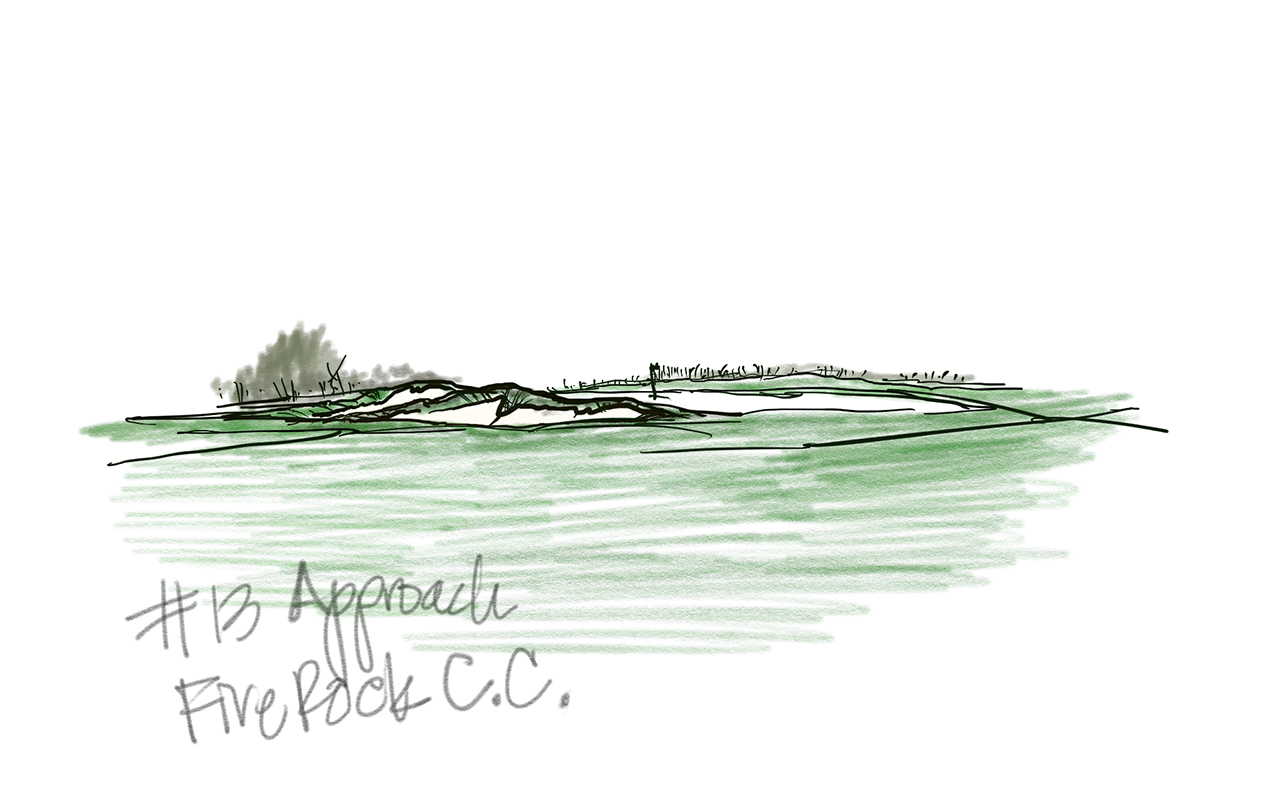

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

-

The renovation process at FireRock Country Club. Credit: Andy Staples

Closing thoughts

“Those misses are going to become less and less.” Andy’s optimism here is striking, even inspiring. Yes, his industry has shrunk and may shrink more. There are very few new-build projects, and most of them go to a handful of the top design firms. That’s worrisome, of course, but Andy chooses to focus on the positive: everyone has been forced to slow down. And when you slow down, you can do good work.

This is one way to deal with hard times. Take a deep breath and recommit to what actually matters.

If you’re sensing an analogy on the horizon, you’re onto me. Golf has changed in the COVID-19 era. More of us are walking, playing alone, and appreciating the simple pleasure of being outdoors. We’ve all slowed down—not in our pace of play, I hope, but in our ability to perceive what’s around us. Without carts and foursomes, we can properly absorb the details of the golf course and enjoy the craftsmanship of the architecture.

The best courses reward this kind of attention because the best owners, builders, and architects don’t rush the process. They slowly learn to collaborate with each other, and they slowly craft every bunker lip, every grassing line, and every hummock and hollow of every green. The industry has given them this time, and they’re taking advantage of it.

My hope is that golfers today can do something similar. If golf becomes quieter and more reflective, let’s make the most of the opportunity to study the landscape around us. And when that landscape is well crafted, let’s acknowledge the many people—owners, architects, and builders—who slowed down, worked together, and made something good.

Further exploration

Community Links

We didn’t discuss it in this episode, but Andy’s “Community Links” initiative is one of the most compelling ideas in public golf architecture today. He has written about it on the Staples Golf Design website and spoken about it on various podcasts, including The Fried Egg and Feed the Ball.

The debate over design-build

As Andy mentioned in our conversation, the shift to a design-build mentality in golf course construction has become a hot-button issue. Most golfers and architects have greeted the change with enthusiasm (see our own Andy Johnson’s essay on golf and “craft culture” and Adam Lawrence’s account of what designers think the future of golf architecture holds), but there are plenty of skeptical voices. In response to Lawrence’s article, Kurt Huseman, president of the construction company Landscapes Unlimited, argued that contractors are essential to efficient golf course construction.

-

Post-renovation Meadowbrook Country Club. Photo credit: Andy Johnson

-

Post-renovation Meadowbrook Country Club. Photo credit: Andy Johnson

-

Post-renovation Meadowbrook Country Club. Photo credit: Andy Johnson

-

Post-renovation Meadowbrook Country Club. Photo credit: Andy Johnson

Extras from the interview with Andy Staples

On tensions between architects’ and contractors’ methods

Andy: I would say another thing about me personally from a design standpoint is, don’t ever ask me what something was supposed to look like. If we worked on a green and had it finalized, and we had the right little nick in the side of the hill, and it had a perfect shadow—and let’s say irrigation came blowing over the top of it and put a mainline right through this awesome feature. The hardest thing for me to do is go back and put it back to where it was, because that was a moment in time. It’s like a painting. It’s like a sculpture. And that’s one of the bigger disconnects I’ve had with contractors. “What do you want? I’ll put it back. Whatever you want.” And I’m like, “Dude, I don’t even know. You can’t recreate that. You should never have done it to begin with.”

Garrett: That seems like a classic tension between the artistic and business sides of the process.

Andy: There is a good analogy of a train that leaves the station. Every car on the train is a phase. You’ve got to shape, you’ve got to put in drainage, and you’ve got to put in irrigation. You have to do the edging and the grassing. And every hole goes through the same process at different times. But the joke is that every single time a new process comes through, it leaves open the opportunity of ruining what you did to begin with. So there’s always this process of saying, okay, let’s go back to the first hole that we started with. We haven’t been there in three months, but we’re about ready to grass it, so let’s get back there. And something’s different. Let’s go figure it out. The people that are putting it all back together again need to understand what you did, and there’s a fine line between what to destroy and what not to destroy.

On maintaining an architectural voice in the midst of a big project

Garrett: The danger of a process that is this complex and that involves so many different people is that the golf course loses your individual stamp as an architect. Your sense of artistry doesn’t get communicated. And if I’m understanding what you’re saying, the keys to making sure that your own perspective comes through in the work are, one, you’re involved very actively in the build process—that one’s obvious—and two, you have a couple of people on the ground day in and day out that you trust and have worked with before and have a common frame of reference with.

Andy: Absolutely. But as many jobs as I do, and as many familiar people as I have on a project, it’s incredible to me how every project seems like we’re starting all over from scratch. And that’s one of the things I love about my business. As much as you think you know, you’re going to find something you haven’t seen before. The way you adjust to those unique qualities of a project is the difference between a really, really good project and an average one.

by

by