Old is new again. Hickory-shafted golf clubs have come back into fashion. Niblicks, mashies, jiggers, brassies—one can acquire all of these in the U.S., both in antique shops and on eBay. Like many hickory golfers, I enjoy the style and history of my clubs, but I play them for a different reason: namely, to best experience the land and the course. Equipment built in the first three decades of the 20th century is my key to appreciating golf course design of the same vintage.

Growing up on Thendara Golf Course in northern New York, I became carefully aware of the differences between early- and mid-20th century golf course architecture. The front nine at Thendara—open, short, and undulating—is a 1921 Donald Ross design. The narrow and woodsy back nine was built by Russell Bailey, an engineer, in 1955. Both sides are enjoyable, but their designs are radically different. One was made for hickory golf, and the other wasn’t.

-

The Ross nine at Thendara (Google Earth)

-

Colin's hickory clubs. Photo credit: Colin Criss

The Ross nine

When I go from modern to vintage equipment, I don’t lose a huge amount of distance on good strikes, but the ball launches lower and with far less spin. Accordingly, a proper hickory golf course has not only shorter holes but also ample room to run shots onto greens, fewer forced carries, and undulations that make the ground game interesting.

The Ross nine at Thendara delivers exactly this kind of design, and I have learned to appreciate it through my hickories. Old is new again. Every hole but one (the “Short” 5th, with its fortified green) provides those who have placed their drives properly a generous runway to various pin positions. At 3,200 yards from the tips, this nine will seem unserious to some—and it did to me at one time. I had grown used to overpowering the course with modern clubs. The bunkering struck me as irrelevant. The green-side bunkers were too far forward of the green, and the fairway bunkers were either too short or too long to affect my typical drives.

Once I began to use hickories, however, these bunkers not only came into play but started to shape my play. I found myself hitting fades and draws to avoid the sand and to find the undulating channels that would feed my ball to the hole.

On the short par-5 4th, it seems smart to play up the right half of the wide fairway to avoid out-of-bounds on the left. With hickories, however, I find second shots from the safe right side of the fairway more difficult. A channel leading to the green gently favors an approach from the left, and the two tall bunkers, both next to the very front of the long green, challenge aerial shots trying to slip over from the right.

The 4th hole at Thendara. Photo credit: Colin Criss

In the hickory era, players commonly carried a club called a jigger. It is an iron of about 30 degrees, with a low clubhead profile and a short shaft. Its design allows for high pitches that bounce and run over coarse grass, and it is crucial to many pre-1935 courses I’ve played, including the Ross nine at Thendara.

Colin's jigger. Photo credit: Colin Criss

Many of the holes on this nine play to elevated greens. For the modern player, this means a lot of spinning short irons. For the hickory golfer, it means a more complex strategy formulated all the way back on the tee. At the 334-yard 3rd, the fairway dips at about the 100-yard marker, then elevates sharply to the green. Even with hickories, a good drive can roll down the hill into the valley. But denied the choice of a spinning lob wedge, the hickory player must make a decision at the beginning of the hole: lay it back to high ground and have a full shot, albeit one that will be difficult to stop on the green; or drive it down the hill and face an intricate uphill running pitch.

This is where the jigger comes in. In front of many of Thendara’s elevated greens, Ross built a small shelf complementary to a jigger’s trajectory. The 3rd is no exception. Initially, the slope in front of the green is steep and bites down on low shots. About two-thirds of the way up the hill, however, the slope shallows into a shelf that extends to the fringe. Although invisible from the fairway, this shelf is essential to the clever hickory player, who can play a half-jigger just short of the green and count on a leaping bounce towards the hole. Here the equipment and the course work together to create fun, complex options for the player and to reward creative shot-making.

-

The approach to the 3rd green at Thendara. Photo credit: Colin Criss

-

Right of the 3rd green at Thendara. Photo credit: Colin Criss

The same is true of the difficult 200-yard 9th hole, where the stomach of the green swells into a giant mound that measures 15 feet wide and 45 feet long. With modern clubs, the long approach is supremely difficult. Only a Herculean effort with a mid-iron will land and stop the ball on top of the mound and next to the common upper pin. Not so with hickories—I’ve found success with my Anderson (St. Andrews) driving iron, hitting a low, three-quarter-swing draw that bounces up the long, flat front of the contour. No doubt Ross shaped this portion of the feature for just this purpose. Again: when played with old clubs, the course encourages and rewards sophisticated shots—shots not only struck well, but hit with intentional weight, trajectory, shape, and spin.

-

The 9th green at Thendara. Photo credit: Colin Criss

-

The 9th green at Thendara from the right. Photo credit: Colin Criss

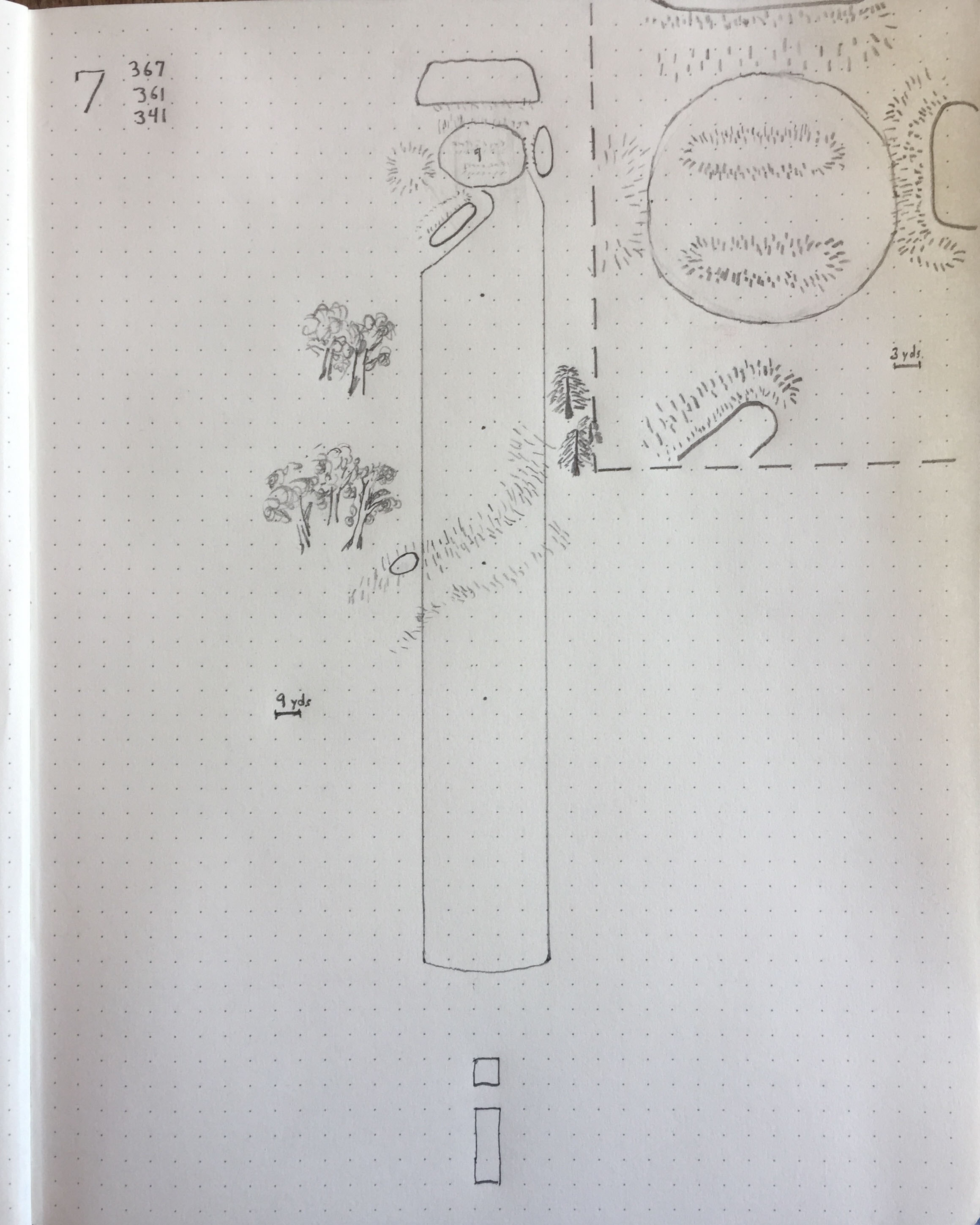

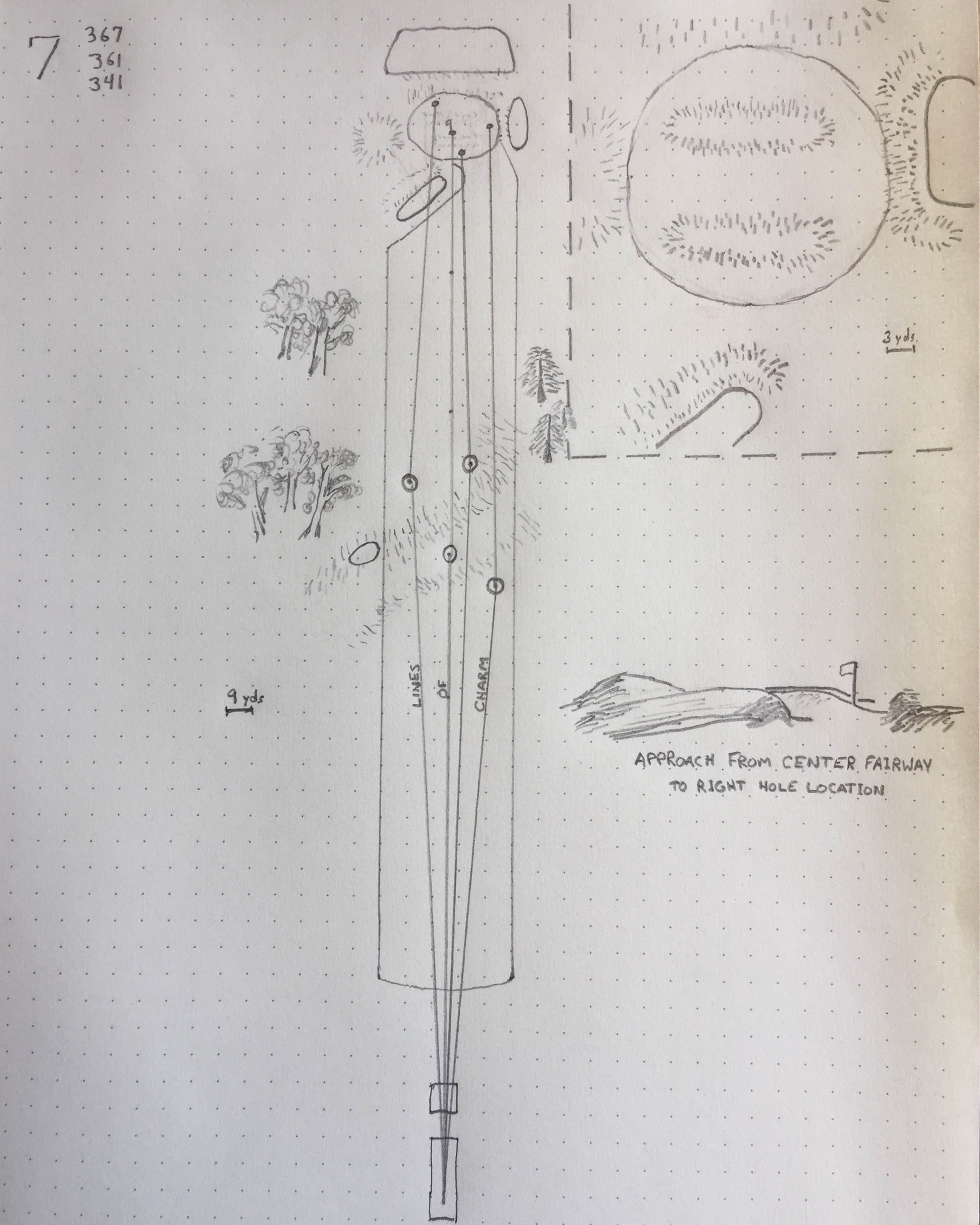

The 7th hole best illustrates the tee-to-green intricacy of Ross’s hickory design at Thendara. With old clubs, either you can attempt a long, right-to-left drive that seeks to bound through a diagonal gully onto the flat reprieve beyond, or you can play short of the gully and to the right in order to preserve a view of the flagstick.

-

Sketch of the 7th hole at Thendara Golf Course. Credit: Colin Criss

-

Sketch of the 7th hole at Thendara Golf Course. Credit: Colin Criss

A further advantage of being short right is access to a runway up to the green, which a long green-side bunker blocks from the left. Not that running the ball up to the hole, even from the right, is an easy task. Two wide, sharp mounds on the green, perpendicular to the line of play, create a variety of pin positions. The hole can be cut in front of both ridges, between them, or behind them. Within each of these sections, the hole can be on the left, guarded by the front bunker; in the center, protected by the steepest sections of the mounds; or on the right, where the flagstick is somewhat exposed but near a side bunker. Getting close to any of these pins with hickories requires a precise command of ball flight.

Moreover, each pin position dictates a different line of charm from the tee, and each line of charm suggests a different hickory shot. For instance, a front pin asks for a long drive past the gully followed by a low, running jigger that skirts the front bunker and uses the first ridge as a backstop. In contrast, a center pin is best attacked from the short-right position, which offers maximal room to run a ball onto the green. From there, with a great sightline, you can run a mid- or long iron over the first mound, and hope the ball doesn’t appear over the second.

The hole plays much trickier, perhaps more than a stroke harder, when the pin is back. In this scenario, the ideal drive hugs the left side of the fairway, especially when the hole is in the back left corner, oddly enough. Since Ross’s mounds stretch most of the way across the green, a ball coming from the right will traverse them on an unpredictable diagonal. But from the left fairway, a barely open channel on the left edge of the green offers the only reliable avenue to a flat birdie putt. The superb hickory golfer can gain access to this putt with a left-to-right shot that lands in this channel.

-

Behind the 7th green at Thendara. Photo credit: Colin Criss

-

Behind the 7th green at Thendara. Photo credit: Colin Criss

-

Left of the 7th green at Thendara. Photo credit: Colin Criss

With modern clubs, the 7th at Thendara is still a fun hole, but there’s no puzzle to it, and no attention demanded to how the features interact with the golf shot. The modern formula: long, straight drive over the gully. Wedge to correct section.

Shots of your own

On the back nine at Thendara Golf Course, play becomes less creative and more formulaic, even with hickories. The narrow, tree-lined 10th, a short par 5, features a steep drop-off 250 yards from the tee. Any tee shot that crests the hill will finish fewer than 150 yards from the green, albeit in the left rough. From there, you are asked simply to loft your second shot at a small and sharply elevated green that drops off on three sides into the woods. Trees on all sides force a certain shot shape, and eagles as well as “others” are possible.

Though a range of possible scores sometimes indicates architectural interest in the modern era, hickory golfers tend to be more interested in a range of possible shots. This is where the 10th hole at Thendara falls short. An uncurving drive down the middle is always best. While the downslope in the fairway presents a strategic choice, the only real options are a longer straight drive or a shorter straight drive. The hole does not vary its demands on weight, trajectory, shape, and spin based on the player’s position. It simply asks you to hit the ball a certain distance in the air and to hit it high.

Golf, this cerebral game, is about challenge and joy. For me, hickory clubs and great Golden Age golf course design enhance these in compounding ways. In challenging the hickory golfer through a varying, strategic landscape, the architect provokes thought. Today, you can willingly enter into that thought by using hickory clubs to impose limits on trajectory and spin. This way, you reap more and more joy from achievement, and your golf ball and its travels become more unique, and more your own.

Colin Criss has an MFA in Poetry from Washington University in St. Louis. For more information about playing with hickories, visit hickorygolfers.com.

This article is part of The Fried Egg’s Sunday Brunch series, which focuses on golf stories that don’t fit the usual categories. Find out more about the series here.

by

by