I’ve been all over the country lately, hosting Fried Egg events at White Bear Yacht Club and Prairie Dunes, covering the Ryder Cup at Whistling Straits, and visiting courses in Boston. I’m exhausted! But I also have a bunch of thoughts about what I’ve seen and what’s been happening in the world of golf architecture. So before I take off for Philadelphia and the Royal Rumble, I figured I’d jot down some notes on the upcoming restorations at Yale and Wakonda, the industry-wide neglect of forward tees, the value of a curious superintendent, and the absurdity of no-walking policies.

Yale finally makes the right move

They say it’s always darkest before dawn. That’s certainly true of Yale Golf Course, which has been through the ringer over the past 18 months. When Covid-19 emptied out the university’s campus, the course suddenly found itself without a general manager, head golf professional, or superintendent. Seth Raynor’s 1926 masterpiece was allowed to go to seed.

Unbelievable. 😩 @Yale @AnthonyPioppi @the_fried_egg @z_blair @NoLayingUp @GeoffShac pic.twitter.com/Ex9bzXRYqb

— Chris (@GolfGuy77) July 2, 2020

As photos of the struggling course circulated, Yale began to hear criticism from its alumni, the local Connecticut community, and the wider golf world. The university, to its credit, responded with action. Peter Palacios was brought on as general manager, and he has turned the facility around. He hired a new superintendent, Jeff Austin from Quail Hollow Club, and course conditions have improved. Best of all, the university decided to restore Raynor’s original design. Yale considered a range of candidates before settling on golf’s leading restoration architect, Gil Hanse.

This is a big deal. The last time Yale put substantial money into its course, it gave the contract to Robert Rulewich, one of its own alumni. Rulewich was known for carrying out designs in the style of his mentor, Robert Trent Jones, but not for restoring Golden Age golf courses faithfully. Rulewich’s work at Yale, carried out in the late 90s and early 00s, was underwhelming, to say the least. His supposed restoration of Raynor’s bunkers was so historically inaccurate that it provoked an outcry in the golf architecture community.

-

Some less-than-historically-accurate bunkers at Yale: No. 2. Photo credit: Andy Johnson

-

Some less-than-historically-accurate bunkers at Yale: Nos. 4 and 5. Photo credit: Andy Johnson

-

Some less-than-historically-accurate bunkers at Yale: No. 8. Photo credit: Andy Johnson

This time around, the university had every opportunity to steer the job to another alum. Instead, it turned to Gil Hanse, a Cornell grad with an exceptional track record in golf course restoration. Hanse got the gig not because of his connections to Yale but because of his well-regarded work at Los Angeles Country Club, Winged Foot Golf Club, Merion Golf Club, Southern Hills Country Club, and many other high-profile courses.

Hanse’s plans are ambitious and will start to go in the ground in the back half of 2022. We’ll wait to see how it turns out, but for now I’m just relieved that Yale’s historic golf course is finally getting the kind of attention and respect that the university has always given to its historic campus buildings.

Sort out your forward tee boxes!

I’ve walked a lot of golf courses in the past few weeks, and I continue to be surprised by how poorly positioned forward tees usually are. The most common problem is that they’re not nearly forward enough. Many golfers can’t hit it farther than 150 yards, and they should be playing courses in the mid-4,000s or less. So why do I keep seeing both private clubs and public courses with forward tees set around 5,500-yard range?

-

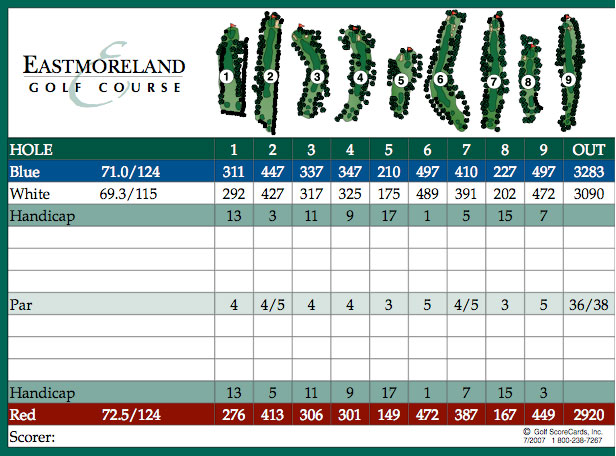

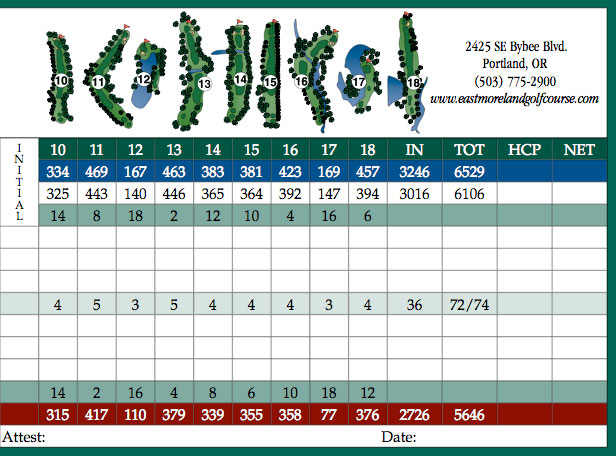

At Eastmoreland, a municipal course in Portland, there's less than a 900-yard difference between the back and forward tees

-

At Eastmoreland, a municipal course in Portland, the total difference between the back and forward tees is less than 900 yards

This is one of the biggest ways in which golf course design and management have failed the game. Forward tees are the entry point for most beginning golfers, regardless of age. They are also important for kids, women, and seniors—three groups that golf courses should be actively courting. So really, the forward tees are the ones we should be putting the most thought into. Instead, they tend to be treated as an afterthought.

In golf course design, 95% of the discourse centers on how holes play from the back tees. We’re certainly guilty of this at The Fried Egg, and during my recent travels, I realized we need to change things up. When we discuss a golf course, we should talk from the forward tees backwards instead of the other way around. We need to pay attention not only to yardages but also to the positioning of the tees, to how they set up holes and engage design features. This simple shift of perspective could do a lot to make the discussion of golf architecture more relevant to the average player.

The inquisitive superintendent

Most superintendents are happy just to keep the grass growing. Michael Vessely, the superintendent of the golf course at Culver Academies in Indiana, has bigger ambitions.

I met Michael in 2017 when I played Culver, a stunning nine-holer designed by Langford & Moreau in 1923. He ended up walking with me and my playing partners—golf architect Riley Johns and media colleagues Jay Rigdon and D.J. Piehowski—for most of our round. He was so gracious, and you could tell he was a sponge, absorbing everything our group said. At the time, Culver was already one of the best nine-hole courses in the country, having undergone a successful restoration by Bobby Weed in 2015. But the mowing lines did not resemble Langford & Moreau’s, and some of the greens had room to expand.

A few more from Culver, here's the par 5 9th and their clubhouse which was modeled after Augusta's-the centerline bunker is roughly 12' deep pic.twitter.com/YD9vO3LN0K

— The Fried Egg (@the_fried_egg) August 23, 2017

Fast-forward four years, and Michael Vessely has made Culver even better. He has done what every golf course superintendent should do: seek out information and input from well-respected people in the industry. He has stayed in regular contact with two outstanding historians, Bob Crosby (a Culver alum) and David Normoyle, and he has scoured the school’s archives for old photos. Michael’s research convinced him to widen the course’s fairways and enlarge its greens and approaches, and he has executed these tasks without an architect’s blessing or significant increases to his budget.

Culver was great in 2016, and there was no particular pressure on Michael to improve it. He would have had little trouble keeping his job if he had simply rolled with the status quo. But instead he stayed curious and took the golf course to the next level, all while getting the most out of a tiny staff and manning a mower every morning.

Here are some examples of the progress Michael and his team have made:

Playing around with some map apps and finally found one that updated most of our new mow lines. Here is the first hole, which we have made even wider this year from fairway bunker to the green #shortgrass #langfordandmoreau pic.twitter.com/1shnhEVzNo

— Michael Vessely (@mdvessely) July 26, 2021

Hole 2 A whole new fair green that slopes severely uphill. Balls that don’t reach the green potentially roll 40 yards back down the hill. Short grass deflection areas help off target shots find the bunkers. The green has recently been mowed out to the approach in the old photo pic.twitter.com/WD13eV9PBK

— Michael Vessely (@mdvessely) July 27, 2021

4th hole fairway way got some width and run into bunker on the right (I know the tree, it’s actually a good target). Green approach was widened a lot and is about to get a little wider 😉. Slopes hard into the green side bunker . pic.twitter.com/7yDqhGPJBO

— Michael Vessely (@mdvessely) July 28, 2021

Hole 5 shoulders were broadened to the left side mostly into the bunker. Short grass all around and fall into the bunker on back right. The green was recently expanded toward the front, in the after photo you can see the lighter bentgrass contrast in front, that is green now pic.twitter.com/slG3xQ0rOl

— Michael Vessely (@mdvessely) July 29, 2021

Hole 6 has my favorite green complex on the course. Widened left side and would like to do right side but am held back because of irrigation. Shots offline will fall into the bunkers all around. pic.twitter.com/QuajoD4GV3

— Michael Vessely (@mdvessely) July 31, 2021

No walkers allowed

Aside from the first-rate modern designs at Streamsong and the model muni at Winter Park, Central Florida is a land of untapped potential. It used to be a hotbed of great golf architecture. At one point or another, nearly every well-known American golf architect of the Golden Age worked there. The owners who hired Raynor, Ross, Tillinghast, etc. in the North brought the same architects south to design winter-getaway courses. Some of these were fantastic; Central Florida, contrary to the state’s overall reputation, is home to some wonderful topography and sandy soils. Unfortunately, most of the area’s Golden Age courses are shells of what they used to be, and some have been mismanaged.

Mission Inn Resort and Club, located in Howie-in-the-Hills, Florida, falls into the latter category. The facility’s El Campeón Course was designed in 1917 by George O’Neill, the Chicago-based architect responsible for the underrated Barrington Hills and the routing of the Beverly Country Club. At El Campeón, O’Neill navigated the sandy terrain expertly, using a large central bowl to create uneven lies and a number of thrilling shots. The current course isn’t completely maximizing the design’s potential, but it’s a great option for public golf in the area.

-

Above Mission Inn's El Campeón course. Photo credit: Andy Johnson

-

The 16th hole at Mission Inn's El Campeón course. Photo credit: Andy Johnson

Unfortunately, Mission Inn strictly prohibits walking at all times. In other words, a golf course designed in an era when everyone walked no longer allows anyone to walk. I asked the club’s head professional about the policy, and he gave me two reasons for it: pace of play, and too many customers trying to save a buck. He explained that if a lower walking rate were available, Mission Inn’s elderly, thrifty clientele would take advantage of it and clog up the course.

It’s hard to know where to start in responding to this reasoning because it’s misguided in many ways, but I settled on suggesting to the pro that he’s missing out on anyone who plays golf for exercise as well as enjoyment. In any case, until Mission Inn lifts its ban on walking, I don’t think I’ll return.

A promising Langford & Moreau restoration

The Yale restoration has gotten the headlines, but I’m just as excited for what’s happening at Wakonda Club in Des Moines, Iowa. Wakonda, designed by Langford & Moreau in 1923, has long been a prime candidate for restoration. It’s a strong routing on a terrific piece of land, but over the years (and through visits by Dick Nugent in 1987 and—guess who?—Robert Rulewich in 2002) it lost many of its bold L&M features. Recently, though, the club took an important step forward by hiring Tyler Rae to carry out a restoration. Rae has done excellent work at Skokie Country Club and the Beverly Country Club, and I’m eager to see what he has in mind for Wakonda. He is currently in the master-planning process and hoping to start work in 2023.

Iowa hasn’t traditionally been known for its golf scene, but between Charles Alison’s Davenport Country Club, Donald Ross’s Cedar Rapids, Keith Foster’s Harvester Club, and a restored Wakonda, the Hawkeye State is a sneaky-good destination.

by

by